Al SmithPhotographs by Tristan Spinski. See more photos from this story <a href="http://fullsite.motherjones.com/media/2014/07/broward-county-public-defenders-portrait">here</a>.

He shot a guy here, he says.

Allen E. Smith and I are sitting in his black Chevy Avalanche with tinted windows, staring out at a small deli in northwest Fort Lauderdale. It was 1976, Smith tells me. He was 28, an officer in the Fort Lauderdale Police Department working a detail that involved watching certain vulnerable stores for robberies. Sure enough, one night while he was crouching under a tree across the way, a robber overpowered the elderly clerk. Smith caught him coming out the door. The guy had a gun in his waistband. Smith had a shotgun. He pumped it and said, “Freeze!” The guy made like he was reaching for his gun. “So I shot him.”

He says this blankly, without a hint of sympathy or remorse. It was his job to protect the store. The job entailed blowing a hole in a man’s torso, and this he did. The guy died a few days later.

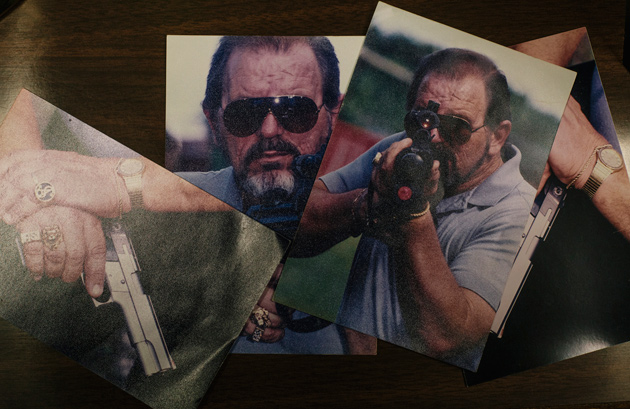

Smith is 65 now, with a rough slab of nose and a deeply grooved forehead. He has a soft voice and he’s not especially huge, but you can tell he used to lift weights; as a younger man, his arms were as thick as his neck. For years, he had an unusual specialty within the department. Whenever the police caught wind that someone was trying to hire a hit man, Smith would offer his services to the plotter. He called himself Al Sanetti, and he did his best to look the part, wearing a gold-nugget bracelet and a lion-head pendant with a diamond in its mouth and rubies for eyes. His business card said only SANETTI SERVICES, with a pager number.

On Smith’s first murder-for-hire investigation, the bar owner proposing to enlist him pointed a .45 at his head and said, “If you are who you say you are, I’ll apologize to you. If you turn out to be something else, I’ll blow your fucking head off.” The guy leaned in to search him. Smith played it cool. Afterward, though, “I told him that one was free, but if he crossed me or pulled a gun on me again, he’d better use it, because I’d hurt him so bad he’d beg me to kill him.” That story made it into Under Contract, a true-crime book about Smith that later became a TV movie.

He drives to another small market and starts telling another story, about another robbery. The suspect this time was younger. “He’s got the gun in one hand and the money in the other. He turns around. I didn’t want to give him a chance to shoot.” Smith’s voice becomes small and far away. “He died.” He falls silent for a few moments. “His teacher from one of the local high schools went to the police department, saying the guy was a good kid, and he never should have gotten shot. Yeah, he probably shouldn’t have. He should have stayed home.”

During his 26 years as a cop, Smith thought he saw things clearly. There were good guys and there were bad guys, and he dealt with some of the worst. But then something changed.

In 1997, Smith retired from the police force. He needed a job to help cover his two daughters’ college expenses, so he signed up as an investigator in the Broward County Public Defender’s Office. He had little idea that he’d end up a key player in a bold experiment in criminal justice, one that aims to give tens of thousands of people who can’t afford lawyers a fighting chance in a system stacked against them. It’s an effort that suggests new ways for court-appointed attorneys to get at the truth, despite their insane caseloads. And a big part of it is getting former cops to police the police.

At the public defender’s office, Smith supervises 11 other investigators, 9 of whom are retired officers like him. Every day, they deploy technology, public records, and good old-fashioned legwork to dig into the sorts of complaints against cops and prosecutors that they used to brush off. In the process, they’re not only turning up evidence of sloppy police work and racial profiling. They’re also finding what they never would have guessed in their previous careers—that some of the sketchy characters they cross paths with are actually innocent.

The legal rationale for America’s system of public defense is simple and clear, and it originated in Florida. In 1961, a drifter named Clarence Gideon was convicted of breaking and entering into a pool hall in the panhandle town of Panama City. He represented himself and lost, but in the prison library he began studying law books, and he wrote to the United States Supreme Court asking for relief. In a landmark 1963 decision, the high court granted Gideon a new trial, arguing that “even the intelligent and educated layman has small and sometimes no skill in the science of law” and that access to a defense attorney was “fundamental and essential to a fair trial.” (Gideon was later acquitted.)

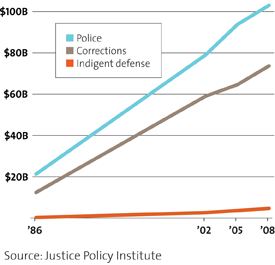

Five decades later, that promise has badly eroded. Due in large part to the rise of the drug war in the ’80s, and budget cuts as municipal finances have gotten squeezed, public defender’s offices have too few lawyers and far too many cases. The National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals and the National Legal Aid & Defender Association have recommended that a public defense attorney should handle no more than 150 felonies or 400 misdemeanors per year. Most offices burn past those limits, sometimes by a factor of two or three.

Al Smith’s boss, Broward County public defender Howard Finkelstein, says the average attorney in his office handles 120 felony cases or 200 to 250 misdemeanors at a time. In neighboring Miami-Dade County, the average noncapital felony caseload for an assistant public defender is 400, almost triple the recommended maximum, and some of the attorneys have juggled up to 700. Criminal caseloads there have grown 29 percent since 2004, even as the office went through waves of belt-tightening. The situation became so dire that county officials went to court in 2008, asking that certain felony cases be handled by the state instead. In May 2013, the Florida Supreme Court approved the request, citing “the breadth and depth of the evidence of how the excessive caseload” has affected poor defendants.

This problem is hardly isolated to Florida. The last time national data was compiled, in 2007, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reported that just 27 percent of county-based public defender’s offices had enough lawyers to avoid exceeding the recommended caseloads.

So what does this mean for defendants? Suppose you get into serious trouble and need an attorney, says Jonathan Rapping, the president of Gideon’s Promise, a group that trains public defenders. You’d expect that attorney to sit down with you and help you understand the charges. You’d expect him or her “to go out and investigate. Knock on doors. Talk to witnesses. File and litigate motions. Be in court.”

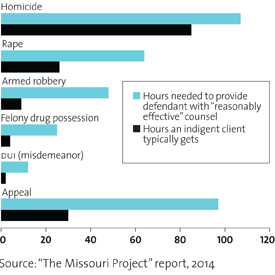

But if the court assigns you a defender saddled with the maximum caseload, you might meet your lawyer for the first time in the courthouse hallway to discuss your hasty plea. In Missouri, according to a 2014 study commissioned by an American Bar Association committee, public defenders typically spend a mere nine hours on a serious felony such as armed robbery—less than one-fifth of what a panel of public and private attorneys agreed was needed to provide “reasonably effective” counsel.

And that’s just the lawyers. The 2007 BJS report found that 40 percent of county public defender’s offices had no investigators at all. “Even the best lawyers in the world, you can only work with what you have,” says Rapping, who started his career as an investigator in the Washington, DC, public defender’s office. “These cases are fact-intensive.” You need people to go out there and pound the pavement, locate hard-to-find witnesses, check alibis. Says Finkelstein, “It’s not like my clients come in and say, ‘Dr. Smith was a witness on this date, so you need to go down to Galt Ocean Drive and get this information.’ Our clients come in and say, ‘Somebody named Junebug, who knows Badass down the street, who hangs out at 11 o’clock at night under the streetlamp’—I gotta find that person.”

To fill what few investigator slots they do have, public defenders often scout for idealistic college grads looking to do good, but these cub investigators burn out quickly. Former cops come in with experience—but that carries its own risks, Rapping says: “On the law enforcement side of things, you can become very jaded. You can come to believe that when someone is accused of a crime, they must have done it.”

Back in downtown Fort Lauderdale, Smith gets out of his Avalanche at the Broward County Courthouse. He walks slowly and with a slight limp. In 2009, he had quintuple-bypass surgery, and he collects disability on account of his exposure to Agent Orange during his years as an Army MP in Vietnam. On the third floor, he enters a waiting room lined with pamphlets offering help for alcohol and drug abuse, opens a door next to the glassed-in receptionist, proceeds past a giant painted gold seal that reads “And Each Shall Stand Equal,” and winds through a series of hallways to his small corner office. It’s lined with photos of his wife, his two daughters and three grandchildren, and of Smith palling around with his old police friends.

Behind his desk, there’s a poster of Sammy Davis Jr. playing pool with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Peter Lawford. (Smith and his partners once called themselves “The Rat Pack.”) Plaques on the wall thank him for his years of police service. One refers to him as “The Gentle Giant.” Another says, “Hit Man.” Scott Israel, who worked alongside Smith in Fort Lauderdale’s organized-crime division and went on to become the county sheriff, told me Smith was trustworthy and highly regarded, the kind of cop you wanted at your side: “He’d go to the gates of hell for another cop.”

Smith isn’t so popular with law enforcement these days. The Fraternal Order of Police, Lodge #32, has revoked his membership, and a picture of his face, he recently heard, was tacked to a bulletin board at police headquarters with a target printed on it. In 2011, a Fort Lauderdale detective used a state database to access personal information about him, presumably in an attempt to dig up dirt. Smith complained to the state attorney’s office, which confirmed the episode but said there was insufficient evidence of criminal conduct and declined to file charges.

When Smith arrived at the public defender’s office in 1997, he wasn’t even sure he could do the job. A few of his cop buddies had asked why he had gone over to the “other side.” He didn’t know what to tell them. The investigative staff was smaller then and included a former Miami Dolphins cheerleader, a former Dolphins running back, a city commissioner, and a judge’s wife. The public defender, a Democratic Party stalwart who’d been in office since 1976, liked to call himself “the Boss Man.” He later came under fire for asking his employees to pony up $100 each to help his daughter’s boyfriend join the Hooters pro golf tour.

Smith kept his head down and started working cases. One involved a young woman charged with writing a counterfeit check in the amount of $4,200. She told a convoluted tale. The gist was that she had recently become unemployed and had gotten the check via FedEx from a company that was offering her a job and had asked her to cash it. As a cop, Smith would have pegged her as a grifter and never given her story a second thought. But he started digging. He traced the FedEx envelope back to a retired fire chief, the kind of guy he was inclined to trust; the chief’s wife explained that her shipping account had been hacked, and fraudsters had used it to send more than 200 bad checks to job seekers all over the country.

It wasn’t the most dramatic case, but at the moment when Smith realized his client was a victim, not a perpetrator, he experienced “a complete change of life.” The ideal of innocent until proven guilty had always struck him as a scam invented by defense attorneys. “Now, on the desk in front of me, lay the key to setting free a totally innocent person,” he later wrote in Florida Defender magazine. “It is hard to describe my exact feelings at that point.” He persuaded prosecutors to drop the charges.

In 2004, seven years after Smith took the job, something else happened to radically change his world: Finkelstein, a blustery former Vietnam War protester, was elected to replace the Boss Man. Finkelstein had gotten into trouble with drugs back in the ’80s—one night he hit a sheriff’s car with his Cadillac, and the deputies busted him with pills and cocaine—but he went to rehab and repaired his reputation with the help of television. During the O.J. Simpson trial, you could find him on air eight hours a day, doing color commentary, and he began to host a twice-weekly legal-advice segment, “Help Me Howard,” for a local news station. Florida is one of only four states whose chief public defenders are elected—not appointed by state boards, judges, or politicians—and Finkelstein’s media presence gave him the name recognition he needed to turn the office into a bully pulpit.

When I sit down with Finkelstein in his spacious courthouse office, he speaks with a gleeful theatricality, as if hundreds are watching, and drops more F-bombs than Tony Soprano. He’s short and wiry, with bronze skin. His gray hair is pulled back in a ponytail. “I am probably the best-known lawyer in all of South Florida,” he says matter-of-factly. “You can walk out anywhere in the street and mention my name and everybody knows me—Help Me Howard! And because of that, I’ve been free to do the right thing.”

Broward is one of Florida’s more liberal counties; it went for Obama by 67 percent in 2012. State Attorney Michael J. Satz, who has been in office since 1976, enjoys a reputation for straight dealing. Yet in January, the Orlando Sentinel reported that Broward is the leading contributor to growth of the state’s prison population. Though crime hit a 43-year low statewide in 2013, and is way down in Broward as well, the number of people the county sent to prison jumped 30 percent that year (a stat the conservative state Senate president blamed on the election of a new sheriff and a fresh slate of tough-on-crime judges). Sometimes Broward’s prosecutions go awry; between 1989 and 2012, 10 of its prisoners were exonerated based on new evidence—more than twice as many as the next closest county. “The world has changed since the mid-’70s,” Finkelstein says. But the county authorities “have not. And that’s the problem.”

After Finkelstein took office, he wasted no time challenging the status quo. One of his first moves, in 2005, was to discontinue the common practice of “meet, greet, and plead.” Often, a public defender would meet his client for the first time at the arraignment and enter a quick no-contest or guilty plea without carefully reviewing the case, in exchange for the client’s release from jail into probation. (Many couldn’t afford bail.) In Broward County, a staggering 80 percent of defendants pleaded guilty at arraignment, a rate even higher than the average for comparable counties. So Finkelstein sent a letter to local judges saying his attorneys would no longer enter guilty pleas without spending real time with their clients.

He also wondered how he could give his overworked lawyers more support. He approached Smith, who had gone to his high school, although the men pursued opposite paths after graduation—Smith going to fight in Vietnam, Finkelstein going to the streets to protest. They got to talking, the recovering addict and the cop.

Finkelstein asked Smith if he knew of any other honest police looking for a second career. (“I’m hiring a fuckin’ 30-year cop for $45,000!” Finkelstein told me. “He’s happier than a pig in shit because he’s got a pension from the city, right? So I’ve just made retirement nice for him.”) Smith put the word out, and when a few of Finkelstein’s senior lawyers retired, it allowed him to save money by replacing them with more-junior attorneys. Before long, Finkelstein had expanded his investigative staff from 7 to 12. “They know more than 50 percent of my lawyers,” he says.

The investigators have a range of experience. Ronald Reffett is a 25-year police veteran; a large man with a white mustache, he keeps a picture on his wall of an eagle crying a single tear above the burning World Trade Center. Clint Ward specialized in white-collar investigations. Phil Arth, who spent much of his 18 years on the force as a homicide detective, has short blond hair and a body out of a video game, a stack of intimidating polygons. For more than a decade, he has taught homicide, robbery, firearms, and building searches at the Broward County Police Academy. Joel Maney is a skinny former undercover narcotics officer with a slick gray mane. Mark Furdon used to be a sergeant on Fort Lauderdale’s Tech Services Squad, responsible for the cameras and communications gear on squad cars—a background that, it turned out, would come in particularly handy in his new job.

All of the guys report to Smith, who spends most mornings sifting through investigative requests from staff attorneys and doling out assignments. Many are dead ends. An investigator might track down a defendant’s alibi witness only to have that person confirm the crime. Each investigator seems to have multiple stories like this. Clients lie. Some people belong in jail.

Other times, though, the investigators unearth surprising facts. “I consider myself going from Z to A now,” Arth says. “As a cop, I went from A to Z. Now I’m going backwards. But it’s amazing what you find when you do that.”

He tells me about a guy named Alvin Batson, a repeat offender charged in 2008 with burglary, assault and battery, and grand theft after allegedly pepper-spraying a homeowner and burglarizing his house. The homeowner identified Batson in a photo lineup, and Batson confessed during a taped interrogation by a detective. When he read the case records, though, Arth noticed that the victim hadn’t identified Batson until he was shown the lineup three times. The detective also threatened “to return to Batson’s mother’s house with the SWAT team and tear the house apart in order to find the victim’s missing computer which might leave Batson’s mother homeless,” according to paperwork on file at the state attorney’s office. “I get to tear up a house today,” the detective said. “That’ll be fun.”

The assistant state attorney on the case called Batson’s interrogation “a creative police interview technique employing humorous exaggeration.” When Arth walked over to the state attorney’s office to insist that the confession was coerced, he was told that a judge would have to determine that. “Well, I teach it,” he tells me. “I teach interrogation. So I kind of know the state statutes.” In the end, the charges were dropped.

The investigators also take advantage of public-record laws to obtain police data they can use to question their former colleagues’ versions of events. For instance, in 2010, a Fort Lauderdale cop named Jefferson Alvarez arrested 29-year-old James Thompson. In his report, the officer wrote that he’d pulled Thompson over after spotting an expired registration tag on his license plate. He charged Thompson for the tag infraction and for repeatedly driving with a suspended license—a third-degree felony. But the electronic data Smith’s team dug up—a GPS report, a computer dispatch report, and a report pinpointing which officers ran information on Thompson and when—revealed that he was parked when Alvarez arrived. (The defendant told Smith he was changing a flat tire for a friend.) Not only that, Alvarez was the third officer on the scene, not the first, as he had stated in a sworn deposition. In the end, Alvarez was charged with perjury and falsifying records. A judge sentenced the cop to three years of probation and community service. The client walked.

In another case that year, officers stopped a man’s car and found 3.5 grams of cocaine. In their report, the officers wrote that they’d pulled the guy over for an unbuckled seatbelt. But a GPS report unearthed by investigator Joel Maney showed that the cruiser, contrary to the official story, was traveling in the same direction as the man’s car; it would have been difficult to see his seatbelt. To be certain, Maney and an assistant public defender went to a used-car lot, found a car of the same model, and photographed the seatbelt from every angle. When one of the arresting officers later testified that he couldn’t remember which direction he’d been traveling, the prosecutor dropped the charges.

But that wasn’t enough for Finkelstein, who wrote to State Attorney Satz, suggesting that he investigate both officers for perjured testimony. The prosecutors demurred. “Every time there’s a discrepancy, they scream that we should file perjury charges,” says Jeff Marcus, Satz’s chief assistant state attorney. “Howard cries wolf quite a bit. But we review each case anyway.”

There’s nothing unique about these kinds of investigative methods. Good criminal-defense attorneys use them as a matter of course—for paying clients. Finkelstein says his goal is to “bring the highest quality of legal service possible to the poorest people in the community.” Yet his office sees about 30,000 cases every year, far too many to deeply investigate each one. So he and his people have also developed a wider, more systematic approach.

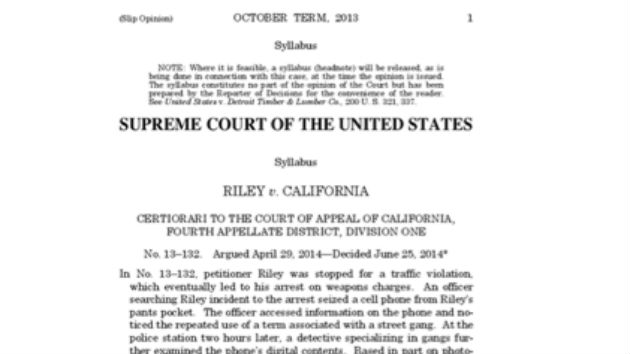

It all began with a 2009 email from a prosecutor to one of Finkelstein’s chief public defenders, Gordon Weekes. The message contained a list of police officers under investigation for misconduct. Prosecutors routinely give information to the defense as part of the discovery process—police reports, surveillance videotapes, etc.—but they are also required by a 1963 Supreme Court decision to provide “Brady” information, any evidence favorable to the defense that could materially affect a verdict.

It was pretty rare at the time, Weekes told me, to get Brady info from the prosecutors, much less a list like this one. Curious, he went back and looked at closed cases in which those officers had testified, but he couldn’t find any Brady notices on them. This was important: If defense lawyers didn’t know that a cop was under investigation, how could they cross-examine him effectively?

Across the country, Brady is hotly contested territory; defense attorneys often complain they don’t get as much information as they should—though many don’t bother. In Broward, the Weekes email sparked a battle. Assistant state attorney Marcus insists the email was no big deal; the prosecutor was busy, so instead of sending out notices case by case, she just sent a bunch at once. But the defenders saw it as proof of prior neglect. In a scathing letter, Finkelstein said Satz’s office had “systematically failed to comply with its Brady obligation.”

Satz shot back that, on the contrary, he was going above and beyond, pointing to a computer system the state has used since 2003 to collect Brady information. The public defenders “are talking about nothing,” Marcus says. “In the last 18 years, there’s no case where we’ve been reversed because of Brady. It’s just nonsense.”

The back-and-forth bickering rests on legal nuances—”It’s a rabbit hole,” Weekes says—and there’s zero common ground. What’s important is that the prosecutors changed their procedures after the defenders raised a stink—and the information began flooding in: “I would have 30 or 40 Brady notices in my box a day,” Weekes says.

Not surprisingly, the defenders wanted more. They started digging deeper, going beyond the formal Brady system to generate their own police misconduct database. They mined public records for every scrap they could find on officers who got in trouble—especially internal-affairs reports and “close-out” memos, written whenever prosecutors wrap up an investigation of an officer without charges. The new system flagged active cases involving cops who’d had allegations sustained against them, information they could use to cross-examine the officers in court. It was “very imaginative,” says Randolph Braccialarghe, a law professor at Nova Southeastern University who worked for Satz for four years. “I don’t think very many people have thought of that before.”

That’s not all they thought of. Around 2011, Smith noticed a puzzling trend in the cases coming across his desk: A lot of black clients were getting arrested for jaywalking in Fort Lauderdale. In one case, a guy was charged with walking on the wrong side of the street where there was no sidewalk; it turned out he’d been standing in front of his own house. A 58-year-old woman was stopped for not using a crosswalk on 6th Street, a main corridor through the black part of town.

Smith and another investigator went to the location and found that the street was under construction, the crosswalk torn up. It was obvious the police had used a pedestrian violation as a pretext to search the woman for drugs. Curious, he asked the police department for a list of all pedestrian violations in the last two years. He then used a yellow highlighter to mark every address that was in a low-income neighborhood. By the time he was done, the list was bathed in fluorescent yellow—93 percent of the addresses were in poor areas. Most of the stops, Smith noted, had been initiated by narcotics officers.

He later performed the same exercise with bicycle stops, calling the police department’s records division for a list of the last three years’ worth of violations of a Fort Lauderdale ordinance requiring residents to register their bicycles with the city. Sifting through more than 450 violations, Smith discovered that 85 percent of the people stopped and cited were black men and boys—and that only 2 percent of the stops took place east of Federal Highway, the main dividing line between the city’s affluent sections to the east and the poor parts to the west. Finkelstein shared the data with the media and wrote a provocative letter to Satz about how his clients were guilty of nothing but “walking while black” and “biking while black.” The police seemed to back off after that, the defenders say.

Since taking office, Finkelstein has consistently picked fights with judges and prosecutors, to the delight of local reporters. “The media grabbed on to me,” he explains. “I’m elfinlike. I’m 5-foot-3. And I’ve got really long hair. I made good copy!” In one case, he filed a complaint against a judge Finkelstein said had made a racist comment about the courthouse’s Haitian cleaning crew.

Another time, he publicly blasted Satz for declining to prosecute a cop who had interrogated a suspected jewelry thief while making the guy stand in a bathtub and threatening to shoot him with a Taser. Finkelstein likened it to torture. (Marcus, Satz’s deputy, calls the claim “outrageous.” His office wrote in a close-out memo that “while this may not have been the best technique to interrogate a suspect, the intent, by all witness accounts, was certainly to help the victims recover their missing items.”)

According to Finkelstein, all of this troublemaking has a higher purpose: to reshape the culture of justice in Broward County. “You really have to apply the forces not just in the courtroom, but you have to shift the social conversation,” he says. “And that can’t be done in a particular courtroom before a particular judge.”

How well are any of these strategies working? It’s difficult to know. Finkelstein says he doesn’t keep a tally of the office’s wins and losses, in part because a win can take so many forms: a not-guilty verdict, a favorable plea deal, a piece of evidence suppressed, a charge never brought, or an arrest never made in the first place. When I call Fort Lauderdale Police Chief Frank Adderley to ask him about the racial-profiling allegations, he sounds weary of the subject: “You know, I’ve done five or six of these interviews.”

Adderley, 52, is the first black police chief in the history of the department. “I live in the area that they’re talking about. And people come to me, their black police chief, who are also black, and victimized. This is a matter of black-on-black crime. You got black offenders, and they’re riding around on bicycles, burglarizing homes, and robbing people at gunpoint,” he says. “So do we say we’re not going to enforce this ordinance because the public defender, who happens to be white, thinks that it’s racial?”

As for Finkelstein’s adversaries in the state attorney’s office, they say his crusading hasn’t changed the way they do business. “Howard is this great, verbose, elegant guy and says all these wonderful things,” spokesman Ron Ishoy tells me in a tone that might be sarcasm or reluctant admiration or both. “All we can do is respond case by case, saying we’re doing a good job.”

Finkelstein insists he has noticed a subtle shift in the local balance of power: a new generosity from prosecutors, a new willingness to share information. “It’s kind of like playing poker,” he says. “They don’t know what we don’t know. And they’re afraid that we might know something. And therefore they don’t want to get caught hiding the ball.”

Whether Finkelstein’s tactics lend themselves to replication is debatable. Most public defenders need support from the police and fire unions that help elect them, or from the judges who appoint them. Finkelstein is unique in his local celebrity, and he’s been able to use it to create elbow room for Smith and his investigators. “The smartest thing I ever did,” he tells me, “was unleash these police officers.”

One sign the Broward crew is on to something is that other public defenders want a peek at its playbook. In November, Gordon Weekes visited the Miami-Dade public defender’s office to tell them about Broward’s techniques for gathering and making use of exculpatory information that prosecutors might not know about, or be willing to hand over. The following month, in Sarasota, he and Smith spoke to another group of defenders from all over the state. Carlos Martinez, Miami-Dade’s chief public defender, told me he was impressed with the apparatus Broward has built. He calls it “an early warning system for when you’re not getting information,” a robust series of checks and balances that has created a justice culture “more responsive to individual rights” and “more respectful of due process. For us, it was eye-opening that we can’t just rely on what the prosecutor is telling you.”

“If I knew what I know now as a police officer, I could have gotten away with a hell of a lot,” Phil Arth, the former homicide detective, tells me one morning. We’re sitting in the tiny office he dwarfs. “Honestly, when I get someone off, it’s a different feeling for me,” he says. “I’ve had a great feeling working homicide, robbery, burglary as a detective. I’d get the people their stuff back, they’re happy. I’ve had in homicide, where I catch the guy, the family members would feel a major loss but still be glad that there’s closure to it. But in this way, I’m actually getting somebody out of jail that is innocent in cases. And I’m thinking, ‘What would it be like if I was in there on some phony charge and had to sit in there?’ I mean, I’ve been in the jail as a detective…and to be there wrongfully charged, I could not imagine it.”

He takes pains to emphasize that he’s no liberal like Finkelstein. “I am very, very conservative. But I’ve changed quite a bit since I’ve been here.” Now, for instance, he sees the logic in diverting mentally ill offenders to special courts, to get them care and keep them out of jail. And he used to feel adamant that some criminals—like the ones who killed three of his fellow officers during his years on the force—deserved to be executed. Now, after spending years looking at capital cases from the defense side, he thinks the death penalty is a waste of time.

Like Smith, he understands why some of his former colleagues won’t talk to him anymore. “They’re furious. They’re furious. Because they’re feeling now that they have to be watched—because of Brady, because of the GPSes, because of modern technology. That everybody’s out to get them.”

“People really don’t understand the crap police take, and for no reason,” Arth continues. “I understand both ways. But I also think there should be a teaching in the middle of that.”

As Smith told me at one point, when you’re a cop, “you kind of develop an attitude that everybody you deal with is an idiot, or they’re criminals, and you tend to judge everybody the same, based on your experiences with the criminals. It’s really not that way. This job has opened my eyes.”

Driving with Smith through Fort Lauderdale one afternoon, I ask him what it was like to play the part of a hit man. “Every day, it’s a different role,” he says. “Sometimes you’re selling drugs. Sometimes you’re protecting a bookmaker or a drug dealer—I kind of showed them what they wanted to see.”

We pass an auto-tinting shop and head through the rough-looking neighborhood in northwest Fort Lauderdale where many of the bicycling and pedestrian cases originated. He mentions a case involving Anthony Caravella, a man with an IQ of 67. At age 16, Caravella was convicted of rape and murder in Broward and spent nearly 26 years in prison, only to be freed by DNA evidence after years of sleuthing by Diane Cuddihy, one of Finkelstein’s attorneys.

Smith worked the case, tracking down witnesses, including a woman who was with Caravella on the day of the murder. Last year, he testified at a federal civil rights trial against the arresting officers; another officer on the case had admitted to Smith that he never believed Caravella had done it. In the end, a jury found that two retired cops had framed Caravella and ordered them (and the department) to pay him $7 million. “That’s kind of a difficult thing, to testify against police officers,” Smith says. “But it’s a case where you care about doing the right thing.”

In his two careers, he tells me, he has seen the extremes of both sides. He has seen people who had to be shot so cops could protect themselves, and he has seen people who had to be protected from the cops. “Everything is not black and white,” he says. He is different now. “I think doing this job has made me a better person.”