Dinga/Shutterstock

On Monday, the Georgia Supreme Court issued a remarkable ruling in a case challenging a Georgia law that designates the source and composition of its lethal-injection drugs as a state secret—one that can be kept hidden from everyone: the condemned, the public, and, most notably, the courts themselves.

That the state’s high court would rule against a death-row inmate is hardly surprising. Georgia courts have rarely voted to spare anyone from execution. But that it would keep the courts ignorant of what goes on in the state’s death chamber seems like an unusual abdication of judicial power.

Georgia passed its secrecy law in March 2013 after its supply of pentobarbital, its primary execution drug, expired. Officials were having trouble getting more, thanks to an export ban by the EU and the refusal of international pharmaceutical companies to sell the drugs for the use in executions. The new law was challenged on behalf of a prisoner named Warren Hill, sentenced to death after killing another inmate while serving a life sentence for murdering his girlfriend. His execution was put on hold last summer, pending the outcome of the challenge.

Under the law Georgia just upheld, the public has no right to obtain the name of any person or company, even under seal in a legal proceeding, who manufactures or sells an execution drug. It also lets state authorities hide the identities of doctors who participate in executions—a professional ethical breach. The secrecy requirements may also be an effort to protect state officials from embarrassment; in 2010 and 2011, the state was shamed by news that it had been illegally importing expired drugs with limited potency from “Dream Pharma,” a London company operating out of the back of a run-down driving school.

Georgia actually used those drugs in two executions before the Food and Drug Administration stepped in and confiscated the supply. But what happened during those executions is one reason Hill wanted more information on the source of the drugs that would be used to kill him. In the first case, the condemned man, Brandon Rhodes, kept his eyes open through the entire process, an indication that the painful paralyzing drugs were administered while he was conscious. During the other state-sanctioned killing, inmate Emmanuel Hammond kept his eyes open, grimaced, and seemed to be attempting to talk.

The high court dismissed these concerns, and insisted that the confidentiality law “plays a positive role in the in the functioning of the capital punishment process.” The court admitted that releasing more information might help satisfy concerns that executions are humane, but found that it was more important that the secrecy made the process “more timely and orderly.”

Really, the court said that.

Two justices dissented loudly, arguing that the ruling creates a “star chamber” situation the courts have long fought to avoid—one that prevents the courts from scrutinizing the execution procedures to ensure they don’t violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. The dissent also points out that the majority ruled against Hill on the grounds that his concerns about potentially contaminated or illegally procured execution drugs were solely “speculative.” But Hill’s claims are speculative, the dissenters wrote, precisely because the court is refusing him the right to information that might make them more concrete. In short, they wrote, there was no way Hill could win, and the majority decision clearly violated his rights to due process.

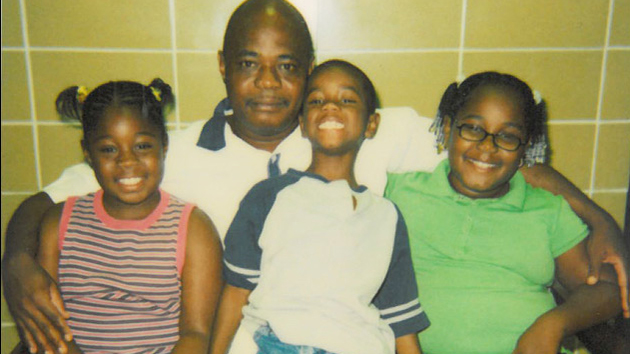

The decision paves the way for the state to continue making itself a a poster child for why the death penalty is on its way out. In 2002, the US Supreme Court banned the execution of mentally disabled people, and Hill, with an IQ of 70, falls into that category. But Georgia doesn’t like being told what to do. So while its lawyers continue to haggle over Hill’s mental state, Georgia may move on to another inmate first: Robert Wayne Holsey, who was convicted of killing a police officer in 1997, even though his court-appointed lawyer, a severe alcoholic, consumed a quart of vodka every night during his trial.

Cases like these suggest that there’s a lot about its capital punishment system that Georgia might prefer to keep secret—not just the drugs it’s using.