tUnE-yArDs videos have a distinctly childlike quality about them. They’re playful and bold, incorporating flamboyant colors, bouncing choreography, and wild costumes. Sometimes they’re full of actual children. Which makes sense, since Merrill Garbus, the creative force behind tUnE-yArDs, wrote some of the act’s first songs years ago while working as a nanny.

The video for “Water Fountain,” from Nikki Nack, her excellent new album on sale this week, borrows a page from Pee-wee’s Playhouse, which Garbus adores. “It was a dream come true,” she told me last week, speaking in an uncharacteristically subdued tone to save her voice for an upcoming world tour.

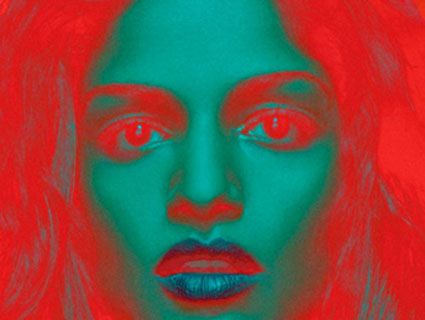

What draws her to children’s art, Garbus says, is the juxtaposition of captivating colors and “very honest messages that can be really dark.” She possesses a certain innocence herself: On Nikki Nack, as on tUnE-yArDs’ past releases, her wailing lyrics are suffused with an exuberance and unabashed honesty that is unique to her sound. “Water Fountain,” Garbus says, “is about my anxiety over the collapse of our societal infrastructure and the lack of drinkable water. It’s a childlike chant, but the words are about heavy topics.”

In many ways, she sees Nikki Nack, named after a character she invented for the album, as a departure from her previous work. Her aim was to stray even further from Western music traditions than she already has. (Studying in Kenya as a Smith College student had a huge influence on her direction, she explained in an earlier chat with Mother Jones.)

After releasing her critically acclaimed 2011 album, whokill, Garbus spent almost two years studying syncopated rhythms—the new album’s original title was Sink-o—and taking drumming lessons with a Haitian dance and performance company in Oakland, California, where she lives. “I realized that most of the music I’m interested in is all syncopated,” she says.

She also spent two weeks in Haiti, where she witnessed Vodou rituals. The trip was a lesson in ancient percussive tradition, and a welcome reprieve from her growing fame. “I went to Haiti as a way to disorient myself from releasing a record and doing interviews, from the pressures of being in a band, and of image,” she told me. “That’s not what feeds me spiritually as a human being.”

The result was a “re-centering” and a “transformation in my understanding of rhythm and music,” not to mention a “rhythmically challenging album.” But Nikki Nack is more than just that. It’s also a document that shows how far she has come in her ability to maintain popular appeal while placing herself squarely outside of the mainstream. For that matter, Garbus says she doesn’t feel any pressure to cede to pop conventions for female performers—like a hypersexualized public persona. “That trivial bullshit will always be there,” she says. As long as people take her music seriously, she doesn’t care what else they think.