This story was originally published in ProPublica.

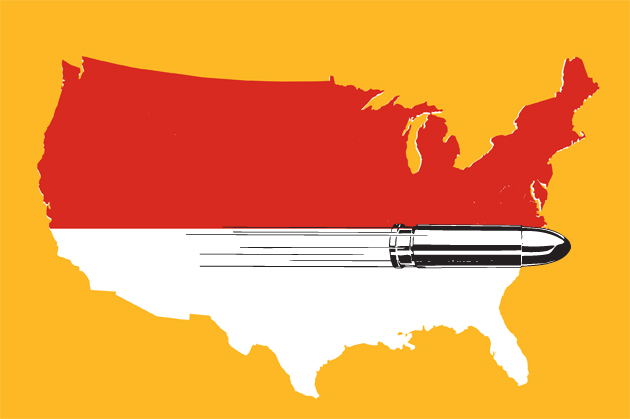

Federal funding for research on gun violence has been restricted for nearly two decades. President Obama urged Congress to allocate $10 million for new research after the Newtown school shooting. But House Republicans say they won’t approve it. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s budget still lists zero dollars for research on gun violence prevention.

One of the researchers who lost funding in the political battle over studying firearms was Dr. Garen Wintemute, a professor of emergency medicine who runs the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California, Davis. Wintemute is, by his own count, one of only a dozen researchers across the country who have continued to focus full-time on firearms violence.

To keep his research going, Wintemute has donated his own money, as the science journal Nature noted in a profile of him last year. As of the end of 2013, he has donated about $1.1 million, according to Kathryn Keyes, a fundraiser at UC Davis’ development office. His work has also continued to get funding from some foundations and the state of California.

We contacted Wintemute to talk about his research, the politics of studying firearms, and how much we really know about whether gun control laws work.

At the end of one of our conversations, Wintemute volunteered that he is also a donor to ProPublica, something the editorial staff had not known. (He and his family’s foundation have donated less than $1,500 over four years.)

Here is the condensed version of our conversations, edited for length and clarity.

What research were you doing when the CDC ended your funding?

We were looking at risk factors for criminal activity among people who had legally purchased handguns. A person can have a misdemeanor rap sheet as long as his arm and still be able to purchase firearms legally in most parts of the country.

In California, there is an archive of handgun transfers. You could draw a random sample of people who purchased handguns and see their overall risk of committing crimes later. We found people who had misdemeanor convictions for nonviolent offenses were five times as likely to commit violence in the future than people with no criminal records. People who had multiple prior misdemeanor convictions for violent crimes [like simple assault and battery or brandishing a firearm] were 15 times as likely to be arrested down the road for crimes like murder and rape and robbery and aggravated assault.

What happened when the CDC cut off your funding?

As I recall, we were in the middle of our project period. We had the expectation that we would be continuing the funds according to the initial award.

When CDC’s funding went away, some private foundations stepped up. But there was a growing sense that little or nothing was going to be done about the problem, at least at the federal level. Why put your money into this one when Congress won’t be doing anything about it?

When did you start donating your own money to keep your research going, and what does the money support?

There came a point when I decided that the work we do is as important as the work of the other nonprofits to which I gave donations. I decided, I’m going to keep the lights on. I told our small staff—three people besides me—I will make that happen personally if need be.

A million dollars is a lot of money. Where does it come from?

Some of it is gifts from stock that was given to me by my father. He’s a businessman. He ran a small company that did well and that’s done well in his retirement. I didn’t earn that. I’ve always seen myself as the steward of that resource.

Some of it is my cash. It boils down to this: I earn an ER doc’s salary. I lead a very simple life. I’m not married, I don’t have kids, I don’t have a television. My rent is $840 a month. It’s easy to save. I don’t drive a fancy car. I don’t go out to eat.

One recent study from Harvard researchers found that there were lower gun death rates in states with more restrictive gun laws. The study got a lot of press. But you’ve been very critical of its conclusions. What’s wrong with this kind of analysis?

Almost all the effects they had seen from mortality in the study had to do with suicide. But the laws were largely intended to prevent homicide.

Number two: Correlation is not causation. Rates of gun deaths are lower where rates of gun ownership are lower. That’s true. We know that. It’s also easier to pass laws like this where the rates of gun ownership are lower. There aren’t that many guns around, there isn’t that large a constituency of gun owners.

States with lots of laws have lower firearm death rates, but the fact that two things occur at the same time does not mean that one of those things caused the other.

So is there any evidence that denying people the right to legally purchase guns has an impact on crime?

[In 1991] California began denying people who had been convicted of violent misdemeanors. Our group took advantage of this natural experiment. Everyone in the study tried to buy a handgun from a licensed seller. One group tried to do it under the terms of the new policy, and their purchases were denied. The other group tried it in the two years before the policy, and their purchases were approved.

The people who got their guns were 25 to 30 percent more likely to be arrested for crimes involving firearms or violence. There was no difference in arrests for crimes that did not involve violence. The difference was specific to the types of crimes the law was supposed to affect.

We also looked at denial for felons and found the same effect. Felons who were denied had a lower risk of being arrested for crimes of violence down the road than were people with felony arrests who were able to purchase their guns.

So do we know whether background checks for all purchases—as President Obama has proposed—would actually prevent violence?

There are not hard data on whether universal background checks work better than what we have at the moment. But there’s lots of suggestive evidence.

One piece of that evidence we have comes from the state of Missouri, a new study by Daniel Webster. Missouri had universal background checks and repealed them. In very short order, there was evidence of increasing gun trafficking. The guns that were recovered after use in crime were getting newer. The inference was it was much easier for people to acquire guns for criminal purposes.

You are planning a broad study about whether comprehensive background checks work. What will that research look like?

Six states—Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Illinois and New York—have just adopted comprehensive background checks, and they’ve all taken effect already. The provisions of their laws vary, and they started from different places.

The intent of our study is to come as close as possible to determining whether there is a causal relationship between comprehensive background check policies and important measures like crime and mortality.

Do you think there’s any chance the CDC will get new funding to resume gun violence research?

I think hell will freeze over before this Congress gives them money. The good news is that funding from other sources is starting to pick up. The National Institute of Health—it’s the first time in their history that they have issued a formal program announcement, a request for proposals on firearms violence.

The NRA has been critical of your work, and says you’re funded by anti-gun groups.

I won’t take money from advocacy organizations.

So, what groups would be on that list?

The National Rifle Association, The Second Amendment Foundation, Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms, the Brady Campaign, Moms Demand Actions, Mayors Against Illegal Guns.

Have you ever accepted funding from former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg?

I have not.

How do you draw the line between nonprofits whose funding you do accept, and “advocacy organizations”?

I’ve been offered money to do studies where the conclusion was basically determined from the design of the study. It wasn’t really science. The organization that was offering to fund the study was also going to control the interpretation of what the analysis meant. They were going to make the decision of whether or not the study got published. As a scientist, I just can’t enter into such an agreement. We have to let people know what the truth is, even if the truth makes someone uncomfortable.

Has your research ever made gun control advocates uncomfortable?

I did a gun show study. When I started crunching numbers on gun show sales, and looking at the surveys, I came to realize—as interesting as this is, gun shows themselves are not a big part of the problem. I felt obligated to add this into my report.

Before we released the study, I had a conference call with a bunch of organizations that I knew were interested in working to close the gun show loophole, and I told them what we were saying. That was a very uncomfortable conversation. People got very angry. It was going to make it more difficult for them to do what they wanted, which was to close the gun show loophole.

You recently did a large survey of federal firearms dealers. What was the most interesting finding?

We learned that a majority—not a large majority, but a majority—of gun dealers and pawn brokers are in favor of comprehensive background checks.

Do you know why some dealers supported background checks and others didn’t?

There is a sense in the country that retailers who have lots of traced guns [i.e. guns that show up at crime scenes] are themselves bad guys, and I just don’t believe that is always the case.

Retailers who had higher frequencies of attempted straw purchases, higher frequencies of attempted off-the-books-purchases, were more in favor of comprehensive background checks. They’re in the business. They know that when they say “no” to somebody, that guy is just going to go somewhere else to someone who says, “yes,” and they don’t want it to happen. They said “no,” so they want the system to say, “No.”

One of the policy proposals you’ve been looking at is whether people with a history of alcohol abuse should also be banned from purchasing firearms. Is this ever going to be a realistic policy — that two DUIs could mean that someone could lose their legal right to buy guns?

Yes. Last year, I floated the idea to the California legislature, and the legislature passed it. The governor vetoed it, or we’d have it now. His veto message said there’s not enough evidence. There’s tons of evidence of alcohol as a risk factor of violent activity. I think he meant evidence specific to gun owners. We’ve started one study, and are in the process of another. We’ll come back with the evidence.