Ken Crane/METRO US/ZUMAPress

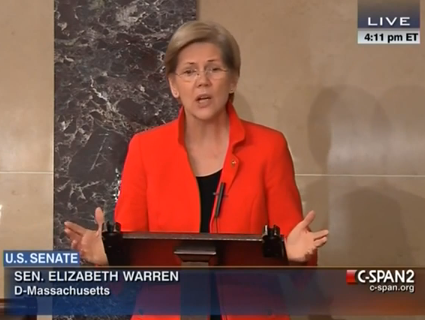

In December, President Barack Obama nominated attorney Sharon Bowen to help run the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), which regulates derivatives and futures markets. Bowen has little experience in derivatives, and she has represented big banks in court. Financial-reform advocates are skeptical that she is the right woman for the job—and are trying to generate opposition to the nominee. But the real question is this: Will middle-class crusader Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) oppose Bowen’s confirmation? And if she did, would that derail Bowen’s candidacy?

If Warren signals she will vote against Bowen, other key senators may follow suit, and that could cause a problem for the White House and Bowen. There’s precedent for this. In September, Warren’s no-vote threat helped scuttle the nomination of former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, whom Obama was considering as chairman of the Federal Reserve.*

Warren has weighed in on Obama’s CFTC picks before. In November, she expressed skepticism about Timothy Massad, the Treasury Department official Obama tapped to be chair of the agency, saying she needs more information about Massad’s views on regulation and his qualifications for the post. (Massad has not yet been confirmed by the Senate.)

Warren has declined to comment on Bowen’s nomination. But there’s reason to suspect she may not approve of this pick. In late November, the Massachusetts senator and eight other Senate Dems sent a letter to Obama urging him to nominate CFTC commissioners who have “demonstrated experience in futures, options and swaps markets” and who possess “the expertise, independence and track record necessary to…provide long overdue oversight to the swap and derivative markets that pose a systemic risk to our economy.” In the same letter, the senators expressed concern that if hard-nosed reformers are not nominated to vacant CFTC posts, Wall Street may have more influence at the agency. “We are deeply concerned that some industry interests may view [these nominations] as opportunities to roll back or slow down essential reforms,” Warren and her colleagues wrote.

Bowen does not have the traits Warren and the others called necessary. She has no record of financial reform and little experience regarding derivatives. (Derivatives are financial instruments with values derived from underlying variables, such as interest rates.) Instead, Bowen is a partner at a Wall Street law firm, Latham & Watkins, that has represented Big Finance clients, including Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, and Deutsche Bank. Michael Greenberger, a law professor at the University of Maryland who previously worked at the CFTC, argues that Bowen’s background will “undoubtedly” make the CFTC more receptive to Wall Street lobbying, just as Warren and her colleagues fear.

Outgoing CFTC Chairman Gary Gensler—an aggressive financial reformer—also started his career on Wall Street and went onto deregulate derivatives at the Treasury Department. When he was nominated in 2009, progressive senators were skeptical that he was the right person to head up the agency. But Gensler allayed their fears by reaching out to financial-reform groups, CFTC commissioners, and senators, and he put forward a plan for regulating derivatives, which had been largely unregulated before the financial crisis. “It was a very impressive document,” says Greenberger. “He made it clear that he understood what problem was and he knew how to fix it.” So far, Bowen has not publicly provided any indications of her priorities for the CFTC, Greenberger says.

The stakes are high. If confirmed, Bowen and Massad—another former Wall Street lawyer who later oversaw the TARP bailout program—would replace two fierce Wall Street critics on the five-member CFTC panel. The two outgoing CFTC commissioners they would succeed—Bart Chilton and Gensler—have taken the lead in drafting surprisingly strong derivatives rules in the face of fierce opposition from Wall Street lobbyists. Bowen and Massad, who are green when it comes to financial reform, could significantly change the composition of the CFTC. Reformers fear they would slow and weaken reform efforts at the agency. The CFTC—which Greenberger calls “probably the most important” Wall Street regulatory agency—still needs to finalize rules determining how much of a particular industry speculators can control and how US banking rules should apply to American firms operating abroad. And the agency must strictly enforce regulations preventing banks from gambling with taxpayer money.

Bowen did not respond a request for comment for this story. Her firm, Latham & Watkins, directed questions to the White House, which did not respond.

If Warren and other Senate Dems oppose Bowen, they may have Republican company. According to Hill staffers, some GOPers are not happy with Bowen’s work as chair of the board of directors of the Securities Investor Protection Corporation, an industry fund that covers losses from brokerage firm failures. SIPC was supposed to compensate the victims of Allen Stanford’s $7 billion Ponzi scheme, but is trying to get out of it. Victims of the $60 billion Madoff ponzi scheme have also been disappointed by what they see as insufficient compensation by SIPC.

“[Bowen] has been a part of all that,” says a Republican Hill aide. Her nomination “give[s] us great pause.”

*This story has been corrected to reflect that the Senate agriculture committee, not the banking committee, vets CFTC nominees.