<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-141199003/stock-photo-spy-is-watching-through-a-hole-in-the-wall.html?src=gw5-h0UbQ3bpO2nsTlSxJw-1-18">Spiber</a>/Shutterstock

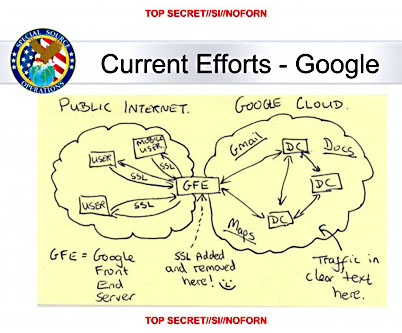

On Thursday, the Senate intelligence committee took a step forward toward officially authorizing some of the National Security Agency’s more controversial surveillance practices, which have recently come to light thanks to leaks from former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. The panel passed out of committee a bill allowing broad phone surveillance to continue under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Backed by the committee chair, Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), the FISA Improvements Act leaves untouched the NSA’s internet surveillance dragnet, PRISM, and does little to improve oversight of the government’s surveillance powers. Feinstein’s bill will face off against legislation introduced earlier this week by Rep. James Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.) and Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) that would significantly curb the government’s ability to sweep up the private information of Americans.

Privacy experts say that the FISA Improvements Act, which passed 11-4, codifies current surveillance practices instead of fixing the law to protect the privacy and civil liberties of Americans: “This was an opportunity for Congress to really recalibrate the statute, and it’s very disappointing that they’ve used this opportunity to cement domestic spying programs instead,” says Michelle Richardson, legislative counsel for the ACLU.

The primary focus of the bill is Section 215 of FISA. This is the part of the law that provides the legal justification for the bulk collection of the telephone metadata of Americans, including phone numbers and the date and duration of calls (but not the content of those conversations). While the bill’s language amends the statute to prevent the NSA from hoovering up phone metadata en masse, it provides gaping loopholes that could allow the agency to continue with its bulk collection practices as usual, such as if there’s a “reasonable articulable suspicion” that an investigation is related to international terrorism. The legislation also makes it legal for the government to collect and search records that are three “hops” from a target who is suspected of terrorism—in other words, a suspect, all of that suspect’s contacts, and all of their contacts. The bill makes only surface fixes and “absolutely allows for the kind of collection that is already happening right now,” according to Amie Stepanovich, the director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center’s (EPIC) Domestic Surveillance Project.

Also worrisome to privacy experts is the fact that the bill expands the NSA’s powers, by allowing the agency to track cellphone’s of non-Americans believed to be located abroad for 72 hours after they enter the United States. The bill additionally levies a penalty of up to 10 years in prison on anyone who accesses NSA information without authorization, like Snowden did.

“The call-records program is legal and subject to extensive congressional and judicial oversight, and I believe it contributes to our national security,” Feinstein said in a statement. “But more can and should be done to increase transparency and build public support for privacy protections in place.”

Feinstein’s modest reforms include limiting the amount of time the government can store the information it collects to five years, with the approval of the attorney general required to search records that are older than three years. And it requires regular reporting to Congress on all FISA violations. The bill also requires the NSA to disclose to the public annually the number of times the agency searched its telephone metadata database.

Feinstein’s surveillance bill will now go head to head with Sensenbrenner and Leahy’s legislation. They introduced companion bills in the House and Senate that would end the bulk collection of phone metadata and put strict limits on the section of FISA that has been used to justify PRISM (so that if the online information of an Americans is accidentally collected, it cannot be searched). The USA FREEDOM Act has been referred to committee.

Unlike the bills introduced by Sensenbrenner and Leahy, Feinstein’s legislation was only made public after it was passed out of committee. EPIC’s Stepanovich notes that the secrecy with the which the Feinstein bill was crafted does not bode well for real reform. “This is the problem with all of these programs,” she says. “You don’t find out about them until it’s far too late, and you have secret collection approved by a secret court, that’s now being reformed by a law that’s kept secret. It is unclear to what substantive ‘improvements’ the title [of the bill] refers to.”