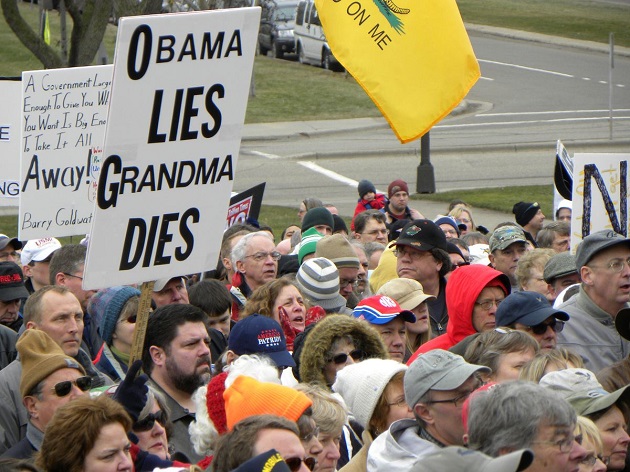

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/fibonacciblue/4430071537/">Fibonacci Blue</a>/Flickr

If you want to understand how American politics changed for the worse, according to moral psychologist and bestselling author Jonathan Haidt, you need only compare two quotations from prominent Republicans, nearly fifty years apart.

The first is from the actor John Wayne, who on the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 said, “I didn’t vote for him, but he’s my president and I hope he does a good job.”

The second is from talk radio host Rush Limbaugh, who on the inauguration of Barack Obama in 2009 said, “I hope he fails.”

The latter quotation, Haidt explains in the latest episode of Inquiring Minds (click above to stream audio), perfectly captures just how powerful animosity between the two parties has become—often overwhelming any capacity for stepping back and considering the national interest (as the shutdown and debt ceiling crisis so unforgettably showed). As a consequence, American politics has become increasingly tribal and even, at times, hateful.

And to understand how this occurred, you simply have to look to Haidt’s field of psychology. Political polarization is, after all, an emotional phenomenon, at least to a large degree.

“For the first time in our history,” says Haidt, a professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business, “the parties are not agglomerations of financial or material interest groups, they’re agglomerations of personality styles and lifestyles. And this is really dangerous. Because if it’s just that you have different interests, that doesn’t mean I’m going to hate you. It just means that we’ve got to negotiate, I want to win, but we can negotiate. If it’s now that ‘You people on the other side, you’re really different from me, you live in a different way, you pray in a different way, you eat different foods than I do,’ it’s much easier to hate those people. And that’s where we are.”

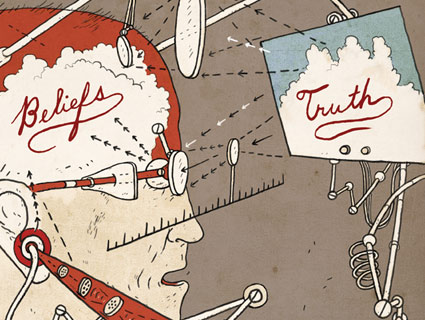

Haidt is best known for his “moral foundations” theory, an evolutionary account of the deep-seated emotions that that guide how we feel (not think) about what is right and wrong, in life and also in politics. Haidt likens these moral foundations to “taste buds,” and that’s where the problem begins: While we all have the same foundations, they are experienced to different degrees on the left and the right. And because the foundations refer to visceral feelings that precede and guide our subsequent thoughts, this has a huge consequence for polarization and political dysfunction. “It’s just hard for you to understand the moral motives of your enemy,” Haidt says. “And it’s so much easier to listen to your favorite talk radio station, which gives you all the moral ammunition you need to damn them to hell.”

Here’s an illustration of the seven moral foundations identified by Haidt, and how they differ among liberals, conservatives, and libertarians, from a recent paper by Haidt and his colleagues.

To unpack a bit more what this means, consider “harm.” This moral foundation, which involves having compassion and feeling empathy for the suffering of others, is measured by asking people how much considerations of “whether someone cared for someone weak and vulnerable” and “whether or not someone suffered emotionally” factor into their decisions about what is right and wrong. As you can see, liberals score considerably higher on such questions. But now consider another foundation, “purity,” which is measured by asking people how much their moral judgments involve “whether or not someone did something disgusting” and “whether or not someone violated standards of purity or decency.” Conservatives score dramatically higher on this foundation.

How does this play into politics? Very directly: Research by one of Haidt’s colleagues has shown, for instance, that Republicans whose districts were “particularly low on the Care/Harm foundation” were most likely to support shutting down the government over Obamacare. Why?

Simply put, if you feel a great deal of compassion for those who lack health care, passing and enacting a law that provides it to them will be an overriding moral concern to you. But if you don’t feel this so strongly, different moral concerns can easily become paramount. “On the right, it’s not that they don’t have compassion,” says Haidt, “but their morality is not based on compassion. Their morality is based much more on a sense of who’s cheating, who’s slacking.”

For Haidt, the political moment that perfectly captured this conservative (and Tea Party) morality—while simultaneously showing how absolutely incomprehensible it is to those on the left—was Wolf Blitzer’s famous gotcha question to Ron Paul during a 2011 Republican presidential debate. Blitzer asked Paul a hypothetical question about a healthy, 30-year-old man who doesn’t get health care because he doesn’t think he needs it, but then winds up in a serious medical situation. When Blitzer asked Paul whether society should just “let him die,” there were audible cheers and cries of “yeah” from the audience—behavior that was appalling to care-focused liberals, but that is eminently understandable, under Haidt’s paradigm, as an emotional outburst based on a very different morality. Watch it:

“My analysis is that the Tea Party really wants [the] Indian law of Karma, which says that if you do something bad, something bad will happen to you, if you do something good, something good will happen to you,” says Haidt. “And if the government interferes and breaks that link, it is evil. That I think is much of the passion of the Tea Party.”

In other words, while you may think your political opponents are immoral—and while they probably think the same of you—Haidt’s analysis shows that the problem instead is that they are too moral, albeit in a visceral rather than an intellectual sense.

As a self-described centrist, Haidt sometimes draws ire from the left for comments about how liberals don’t understand their opponents, and about how conservatives have a broader range of moral emotions. But he certainly doesn’t claim that when it comes to political animosity and the polarization that we now live under, both sides are equally to blame. “The rage on the Republican side is stronger, the Republicans have gotten much more extreme than the Democrats have,” Haidt says.

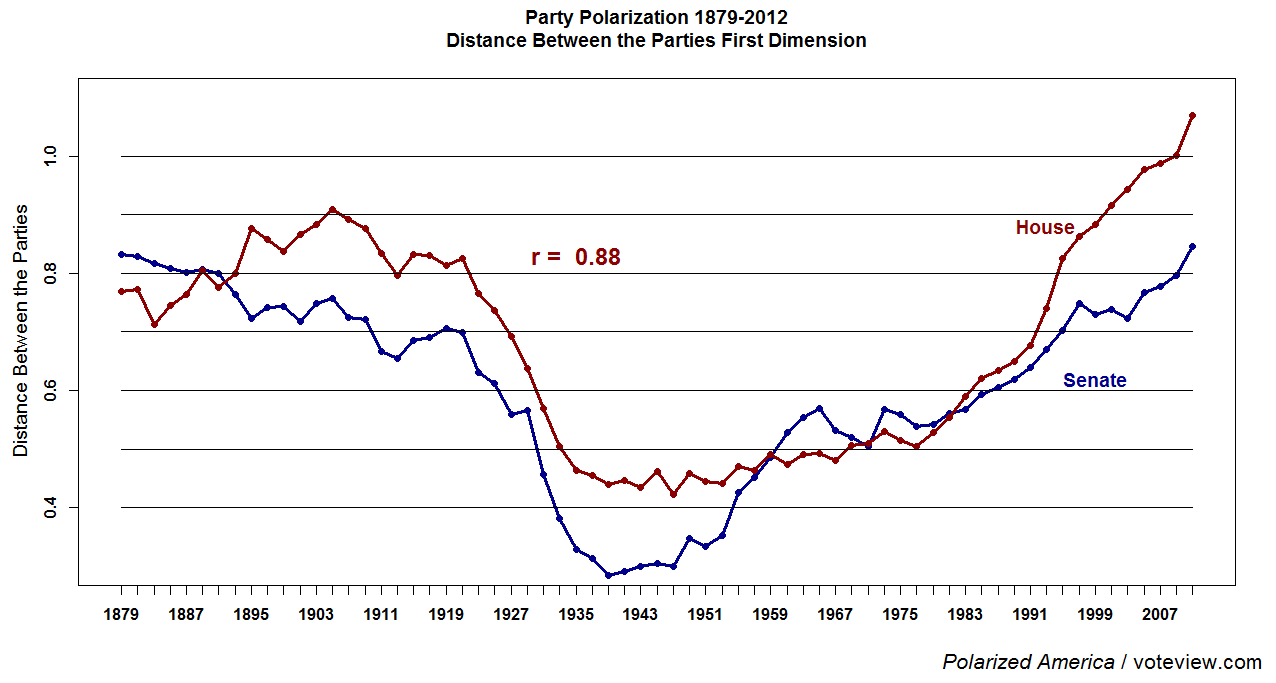

The data on polarization are as clear as they are disturbing. Overall, feelings of warmth towards members of the opposite party are at terrifying lows, and Congress is perhaps more polarized than it has been in the entire period following the Civil War:

But this situation isn’t the result of parallel changes on both sides of the aisle. “The Democrats, the number of centrists has shrunk a bit, the number of conservative Democrats has shrunk a bit, but it’s not that dramatic, and the Democratic party, certainly in Congress, is a mix of centrists, moderately liberal and very liberal people,” says Haidt. “Whereas the Republicans went from being overwhelmingly centrist in the ’50s and ’60s, to having almost no centrists,” Haidt says.

And of course, the extremes are the most morally driven, the most intense.

From the centrist perspective, Haidt recently tweeted that “I hope the Republican party breaks up and a new party forms based on growth, not austerity or the past.”

“This populist movement on the right,” he says, is “sick and tired of the allegiance with business.” And more and more, business feels likewise, especially after the debt ceiling and shutdown disaster.

“I think this gigantic failure might be the kind of kick that some reformers need to change how the Republicans are doing things,” says Haidt. “That’s my hope, at least.”

For the full interview with Jonathan Haidt, listen here:

This episode of Inquiring Minds, a podcast hosted by bestselling author Chris Mooney and neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas, also features a discussion of new research on how marmosets are polite conversationalists (seriously) and of how Glenn Beck doesn’t understand statistics.

To catch future shows right when they release, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes. You can also follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook.