It adds up.Tim Murphy

About three weeks ago I was walking home from the grocery store when a group of teenagers demanded my wallet, cellphone, and—for reasons I can’t fully explain—gallon of whole milk. Although I made no effort to resist, I ended up with a laceration on my lip that required stitches, fairly intense swelling on both sides of my head that required X-rays, and a bruised rib. And I was down a gallon of milk and a dozen eggs. It sucked.

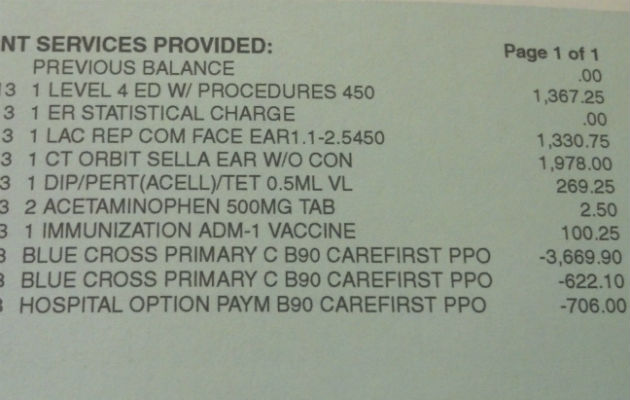

On Tuesday, though, I got some good news—a billing statement from George Washington University Hospital, where I got my stitches, CAT scan, painkillers, and a tetanus shot. Thanks to my employer-provided insurance company, Carefirst Blue Cross Blue Shield, I ended up paying about $50. But if I didn’t have insurance, like 47 million working-age adults nationally and approximately 23 percent of 18-to-25-year-olds, it would have increased the bill by a factor of more than a hundred. The sutures alone were $1,400, and another $300 to have them taken out four days later. I’m a young journalist at a nonprofit magazine. I do my best to budget responsibly. But I don’t have $5,000 of disposable income just lying around. My unfortunate encounter with typically wayward millennials could have left me broke.

I mention this because conservative lawmakers have spent much of the last four years—and the three weeks since the Affordable Care Act’s exchanges opened on October 1—arguing that emergency rooms are a suitable replacement for having health insurance. “We do provide care for people who don’t have insurance,” Mitt Romney explained during his 2012 presidential campaign. “If someone has a heart attack, they don’t sit in their apartment and die.” During last year’s campaign, now-Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) took heat from doctors groups when he argued against all evidence that it would be cheaper for the state to keep sending the 6.1 million Texans who lack health insurance to emergency rooms than it would to expand Medicaid. And in 2011, then-Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour (R) explained that he was rejecting the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion in the nation’s poorest and unhealthiest state because “there’s nobody in Mississippi who does not have access to health care.” After all, his office explained, there was always the emergency room.

But by the time the uninsured get to the emergency room, the damage has already been done. According to a study from Harvard Medical School, someone dies as a consequence of not having health insurance about once every 12 minutes in the United States, because they aren’t able to seek basic primary care treatment that can prevent more serious problems. (About 9,000 Texans will die each year as a result of Gov. Rick Perry’s rejection of the Medicaid expansion, according to an analysis by the Institute for Medical Humanities at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.) But Barbour and his colleagues missed the broader economic point: Someone has to pay for emergency room visits. Emergency care can help literally stop the bleeding—it did in my case. But it’s expensive, and it’s not a substitute for regular primary care or health insurance.

In recent months, conservative groups like FreedomWorks and the Koch Brothers-backed Generation Opportunity have sought to dissuade young Americans from purchasing health insurance, arguing that millennials are being forced to pay disproportionately high prices for something they’re disproportionately less likely to need. But random crime can happen to anyone—and young people are disproportionately unlikely to be able to pay out of pocket.

If you get mugged in Washington, DC, and you’re uninsured, you have some help. As the detective assigned to my case helpfully informed me, the District covers up to $25,000 in medical expenses for victims of violent crime. But there are plenty of other ways to mess up your face that don’t involve felonies, and plenty of violent crimes that will send your bill sailing far north of $25,000. (Just consider the case of Salon reporter Brian Beutler.) The numbers back this up: A 2012 study from the Commonwealth Fund found that 51 percent of uninsured young adults—the healthiest age group in the United States—had trouble paying medical bills.

So if you’re uninsured and can afford a basic plan, you should get insured—because while your odds of going to the emergency room on any given day are statistically low, your odds of being financially ruined if you do are quite high. Otherwise, it just might cost you the arm and a leg you were trying to save.