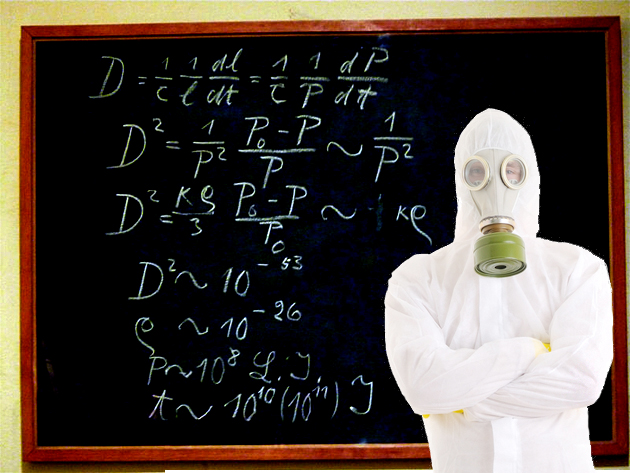

State troopers clean up a meth lab found on school board property about a block from a London, Kentucky elementary school.Photos by Stacy Kranitz. See <a href="http://fullsite.motherjones.com/politics/2013/08/photoessay-meth-laurel-county-kentucky-kranitz">more of her photos</a> from Laurel County, Kentucky.

The first time she saw her mother passed out on the living room floor, Amanda thought she was dead. There were muddy tracks on the carpet and the room looked like it had been ransacked. Mary wouldn’t wake up. When she finally came to, she insisted nothing was wrong. But as the weeks passed, her 15-year-old daughter’s sense of foreboding grew. Amanda’s parents stopped sleeping and eating. Her once heavy mother turned gaunt and her father, Barry, stopped going to work. She was embarrassed to go into town with him; he was covered in open sores. A musty stink gripped their increasingly chaotic trailer. The driveway filled up with cars as strangers came to the house and partied all night.

Her parents’ repeated assurances failed to assuage Amanda’s mounting worry. She would later tell her mother it felt “like I saw an airplane coming in toward our house in slow motion and it was crashing.” Finally, she went sleuthing online. The empty packages of cold medicine, the canisters of Coleman fuel, the smell, her parents’ strange behavior all pointed to one thing. They were meth cooks. Amanda (last name withheld to protect her privacy) told her grandparents, who lived next door. Eventually, they called police.

Within minutes, agents burst into the trailer. They slammed Barry up against the wall, put a gun to his head, and hauled him and Mary off in handcuffs. It would be two and a half years before Amanda and her 10-year-old sister, Chrissie, would see their father again.

The year was 2005, and what happened to Amanda’s family was the result of a revolution in methamphetamine production that was just beginning to make its way into Kentucky. Meth users called it the “shake- and-bake” or “one-pot” method, and its key feature was to greatly simplify the way meth is synthesized from pseudoephedrine, a decongestant found in cold and allergy medicines like Claritin D and Sudafed.

Shake and bake did two things. It took a toxic and volatile process that had once been the province of people with Breaking Bad-style knowledge of chemistry and put it in the bedrooms and kitchens of meth users in rural America. It also produced the most potent methamphetamine anywhere.

If anyone wondered what would happen if heroin or cocaine addicts suddenly discovered how to make their own supply with a handful of cheap ingredients readily available over the counter, methamphetamine’s recent history provides an answer. Since 2007, the number of clandestine meth sites discovered by police has increased 63 percent nationwide. In Kentucky, the number of labs has more than tripled. The Bluegrass State regularly joins its neighbors Missouri, Tennessee, and Indiana as the top four states for annual meth lab discoveries.

As law enforcement agencies scramble to clean up and dispose of toxic labs, prosecute cooks, and find foster homes for their children, they are waging two battles: one against destitute, strung-out addicts, the other against some of the world’s wealthiest and most politically connected drug manufacturers. In the past several years, lawmakers in 25 states have sought to make pseudoephedrine—the one irreplaceable ingredient in a shake-and-bake lab—a prescription drug. In all but two—Oregon and Mississippi—they have failed as the industry, which sells an estimated $605 million worth of pseudoephedrine-based drugs a year, has deployed all-star lobbying teams and campaign-trail tactics such as robocalls and advertising blitzes.

Perhaps nowhere has the battle been harder fought than in Kentucky, where Big Pharma’s trade group has broken lobbying spending records in 2010 and 2012, beating back cops, doctors, teachers, drug experts, and lawmakers from both sides of the aisle. “It frustrates me to see how an industry and corporate dollars affect commonsense legislation,” says Jackie Steele, a commonwealth’s attorney whose district in southeastern Kentucky has been overwhelmed by meth labs in recent years.

Before it migrated east to struggling Midwestern farm towns and the hollers of Appalachia, methamphetamine was a West Coast drug, produced by cooks working for Mexican drug-trafficking organizations and distributed by biker gangs. Oregon was particularly hard hit, with meth labs growing ninefold from 1995 to 2001. Even then, before shake and bake, police had their hands full decontaminating toxic labs that were often set up in private homes. Social workers warned of an epidemic of child abuse and neglect as hundreds of kids were being removed from meth houses.

In despair, the Oregon Narcotics Enforcement Association turned to Rob Bovett. As the lawyer for the drug task force of Lincoln County—a strip of the state’s central coast known for its fishing industry, paper mills, and beaches—he was all too aware of the scourge of meth labs. Having worked for the Oregon Legislature and lobbied on behalf of the State Sheriffs’ Association, he also knew his way around Capitol procedure.

Bovett knew that law enforcement couldn’t arrest its way out of the meth lab problem. They needed to choke off the cooks’ supply lines.

Bovett first approached the Legislature about regulating pseudoephedrine in 2000. “The legislative response was to stick me in a room with a dozen pharmaceutical lobbyists to work it out,” he recalls. He suggested putting the drugs behind the counter (without requiring a prescription) to discourage mass buying, but the lobbyists refused. They did eventually agree to a limit on the amount of pseudoephedrine any one person could buy, but the number of meth labs remained high, so in 2003 Bovett tried once again to get pseudoephedrine moved behind the counter. “We got our asses kicked,” he admits.

Then, in Oklahoma, state trooper Nikky Joe Green came upon a meth lab in the trunk of a car. The cook overpowered Green and shot him with his own gun. The murder, recorded on the patrol car’s camera, galvanized the state’s Legislature into placing pseudoephedrine behind the counter and limiting sales in 2004.

The pharmaceutical industry fought the bill, saying it was unlikely to curb meth labs. But Oklahoma saw an immediate drop in the number of labs its officers busted, and Oregon followed suit later that year.

But the meth cooks soon came up with a work-around: They organized groups of people to make the rounds of pharmacies, each buying the maximum amount allowed—a practice known as smurfing. How to stop these sales? Bovett remembered that until 1976, pseudoephedrine had been a prescription drug. He asked lawmakers to return it to that status.

Pharma companies and big retailers “flooded our Capitol building with lobbyists from out of state,” he says. On the eve of the House vote, with the count too close to call, four legislators went out and bought 22 boxes of Sudafed and Tylenol Cold. They brought their loot back to the Legislature, where Bovett walked lawmakers through the process of turning the medicine into meth with a handful of household products. Without exceeding the legal sales limit, they had all the ingredients needed to make about 180 hits. The bill passed overwhelmingly.

Since the bill became law in 2006, the number of meth labs found in Oregon has fallen 96 percent. Children are no longer being pulled from homes with meth labs, and police officers have been freed up to pursue leads instead of cleaning up labs and chasing smurfers. In 2008, Oregon experienced the largest drop in violent-crime rates in the country. By 2009, property crime rates fell to their lowest in 43 years. That year, overall crime in Oregon reached a 40-year low. The state’s Criminal Justice Commission credited the pseudoephedrine prescription bill, along with declining meth use, as key factors.

For Big Pharma, however, Oregon’s measure was a major defeat—and the industry was not about to let it happen again. “They’ve learned from their mistakes in Oregon, they’ve learned from their mistakes in Mississippi,” says Marshall Fisher, who runs the Bureau of Narcotics in Mississippi. “They know if another state falls, and has the results that we’ve had, the chances of national legislation are that much closer. Every year they can fight this off is another year of those profits.”

On a sunny winter afternoon, narcotics detective Chris Lyon turns off a country lane outside the town of Monticello in southeastern Kentucky, the part of the state hardest hit by the meth lab boom. In a case that shocked the state in 2009, a 20-month-old boy in a dilapidated trailer nearby drank a cup of Liquid Fire drain cleaner that was being used to make meth. The solution burned Kayden Branham from inside for 54 minutes until he died.

This afternoon, Lyon is following up on a call from a sheriff’s deputy about several meth labs in the woods. His Ford F-150 clambers up a steep muddy slope turned vivid ochre by the night’s rain. In the back are a gas mask, oxygen tanks, safety gloves, and hazmat suits, plus a bucket of white powder called Ampho-Mag that’s used to neutralize toxic meth waste. Cleaning up labs is hazardous work: In the last two years, more than 180 officers have been injured in the process. The witches’ brew that turns pseudoephedrine into meth includes ammonium nitrate (from fertilizer or heat packs), starter fluid, lithium (from batteries), drain cleaner, and camping fuel. It can explode or catch fire, and it produces copious amounts of toxic gases and hazardous waste even when all goes well.

Halfway up Edwards Mountain, Lyon pulls over in a clearing along the forested trail. Scattered over 50 yards are a half-dozen soda bottles, some containing a grayish, granular residue, others sprouting the plastic tubes cooks use to vent gas. Lyon snaps on black safety gloves, pulls a gas mask over his face, and carefully places each bottle in its own plastic bucket. Further up the mountain he finds more outdoor labs and repeats the procedure.

Lyon will drive his haul back to the Monticello Police Department, where a trailer is jam-packed with buckets he’s filled in the past few days. “No suspects, no way of making an arrest—it’s pretty much a glorified garbage pickup,” he says with an air of dejection. “We have all kinds of information of people selling drugs,” but there’s no time for investigations. “About the time that we get started on something, the phone rings and it’s another meth lab to go clean up.”

It’s a problem Lieutenant Eddie Hawkins, methamphetamine coordinator for the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics, was all too familiar with before his state passed its prescription bill in 2010. Since then the number of meth labs found in the state has fallen 74 percent. “We still have a meth problem,” Hawkins says, “but it has given us more time to concentrate on the traffickers that are bringing meth into the state instead of working meth labs every night.” Now, he says, they go after international criminal networks rather than locking up small-time cooks.

The spread of meth labs has tracked the hollowing out of rural economies. Labs are concentrated in struggling towns where people do hard, physical work for low wages, notes Nick Reding, whose book Methland charts the drug’s rise in the Midwest: “Meth makes people feel good. Even as it helps people work hard, whether that means driving a truck or vacuuming the floor, meth contributes to a feeling that all will be okay.” But the highly addictive drug can also wreak havoc on users, ravaging everything from teeth and skin to hearts and lungs. And the mushrooming of shake-and-bake labs has left its own trail of devastation: hospitals swamped with injured meth cooks, wrecked and toxic homes, police departments consumed with cleaning up messes rather than fighting crime.

Meth-related cleanup and law enforcement cost the state of Kentucky about $30 million in 2009, the latest year for which the state police have produced an estimate. That doesn’t include the cost of crimes addicts commit to support their habit, of putting out meth fires, of decontaminating meth homes, of responding to domestic-abuse calls or placing neglected, abused, or injured kids in foster care. Dr. Glen Franklin, who oversees the burn unit at the University of Louisville Hospital, says his unit alone sees 15 to 20 meth lab burn patients each year, up from two or three a decade ago. They are some of his most difficult cases, often involving both thermal and chemical burns to the face and upper body from a bottle that burst into flames. Many, he notes, have also been abusing OxyContin or other prescription opiates, “so it makes their pain control that much more difficult.” According to a study coauthored by Franklin in 2005, it costs an average of nearly $230,000 to treat a meth lab victim—three times more than other burn patients—and that cost is most often borne by taxpayers. Meth use as a whole, according to a 2009 RAND Corporation study, costs the nation anywhere between $16 billion and $48 billion each year.

With silver hair, glasses, and a gentle manner, Linda Belcher looks like the retired grade school teacher she is. Though her district, just south of Louisville, has a meth lab problem, she didn’t know much about the issue until Joe Williams, the head of narcotics enforcement at the Kentucky State Police, invited her and a few other lawmakers to state police headquarters. After a dinner of barbecue, coleslaw, and pork and beans, the guests descended to the basement to be briefed about key public safety issues. One was meth labs, whose effects and increasing numbers were depicted in a series of huge charts. One of Williams’ officers laid out the startling facts. Meth labs were up for the second year in a row in Kentucky, and they were spreading eastward across the state. They were turning up in cars, motel rooms, and apartment buildings, putting unsuspecting neighbors at risk. Police had pulled hundreds of children from meth lab locations. Prisons were filling up with cooks, and officers were being tied up in cleanup operations.

Belcher had been aware of methamphetamine, but she’d had no idea how bad things were getting. She set about learning more. “I went to a meeting and there was a young lady there who had been on meth,” Belcher recalls. “During the time she was on it, she didn’t care about anything—not her daughter, not her parents. All she wanted was to get money and get meth. That convinced me.”

Belcher asked Williams and other law enforcement officials what they thought should be done. They told her about what had happened in Oregon. It could work in Kentucky, they said. In February 2010, Belcher filed a bill to require a prescription for pseudoephedrine.

Soon her phone started ringing off the hook. The callers were angry. If her bill passed, they said, they would have to go to the doctor each time they were congested. It wasn’t true—more than 100 cold and allergy drugs made without pseudoephedrine, such as Sudafed PE, would have remained over the counter. And for those who didn’t like those alternatives, doctors could renew prescriptions by phone.

Members of the House Health and Welfare Committee, the key panel Belcher’s bill had to clear, were also getting calls. Tom Burch, the committee’s chairman, says the prescription measure garnered more calls and letters than any he’s dealt with in his nearly 40 years at the Capitol, except for abortion bills. “I had enough constituent input on it to know that the bill was not going to go anywhere.”

Yet the legislation had gotten hardly any media coverage. How had Kentuckians become so outraged?

In April of that year, Donnita Crittenden was processing monthly lobbying reports at the Kentucky Legislative Ethics Commission when a figure stopped her in her tracks. A group called the Consumer Healthcare Products Association reported having spent more than $303,000 in three weeks. No organization had spent nearly that much on lobbying in the entire previous year.

Curious, Crittenden called CHPA. It was, she learned, a Washington-based industry association representing the makers and distributors of over-the-counter medicines and dietary supplements—multinational behemoths like Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. CHPA had registered to lobby in Kentucky just weeks before, right after Belcher filed her bill. But it had already retained M. Patrick Jennings, a well-connected lobbyist who’d earned his stripes working for Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and GOP Rep. Ed Whitfield.

The bulk of CHPA’s record spending, though, was not for lobbyists. It was for a tool more commonly used in hard-fought political campaigns: robocalls, thousands of them, with scripts crafted and delivered by out-of-state PR experts to target legislators on the key committees that would decide the bill’s fate.

CHPA’s Kentucky filings don’t show which firm made the robocalls, but the association’s 2010 and 2011 tax returns show more than $1 million worth of payments to Winning Connections, a robocall company that typically represents Democratic politicians and liberal causes such as the Sierra Club’s campaign against the Keystone XL pipeline. On its website, the company boasts of its role in West Virginia, where it helped defeat a pseudoephedrine bill that had “strong backing among special interests groups and many in the State Capitol” via focused calls in key legislative districts. CHPA’s former VP for legal and government affairs, Andrew C. Fish, is quoted as saying that Winning Connections helped “capture the voice of consumers, which made the critical difference in persuading legislators to change course on an important issue to our member companies.” Nowhere does Winning Connections’ site mention the intent of the bill or the word “methamphetamine.” CHPA spokeswoman Elizabeth Funderburk says the association used the calls, which allowed people to be patched through directly to their legislators, to provide a platform for real consumers to get their voices heard.

Belcher’s bill never came up for a vote. Over the ensuing months, the number of meth labs found in Kentucky would grow by 45 percent, surpassing 1,000.

Belcher had learned a lesson. When she reintroduced the prescription bill in 2011, it had support from a string of groups with serious pull at the Capitol—the teachers’ union, the Kentucky Medical Association, four statewide law enforcement organizations, and Kentucky’s most senior congressman, Hal Rogers. Belcher also had bipartisan leadership support in the Legislature, and the Republican chairman of the judiciary committee, Tom Jensen—whose district included the county with the second-highest number of meth labs—introduced a companion bill in the state Senate.

But the pharmaceutical industry came prepared, too. Its team of lobbyists included some of the best-connected political operatives in Kentucky, from former state GOP chairman John T. McCarthy III to Andrew “Skipper” Martin, the chief of staff to former Democratic Gov. Paul Patton. In addition to a new round of robocalls, CHPA now deployed an ad blitz, spending some $93,000 to blanket the state with 60-second radio spots on at least 178 stations. The bill made it out of committee, but with the outcome doubtful, Jensen never brought it up for a vote on the Senate floor.

John Schaaf, the Kentucky Legislative Ethics Commission’s counsel, describes CHPA’s strategy as a game changer. “They have completely turned the traditional approach to lobbying around,” he says. “For the most part, businesses and organizations that lobby, if they have important issues going on, they’ll add lobbyists to their list. They’ll employ more people to go out there and talk to legislators. CHPA employs very few lobbyists and they spend 99 percent of their lobbying expenditures on this sort of grassroots outreach on phone banking and advertising. As far as I know, nothing’s ever produced the number of calls or the visibility of this particular effort.”

In other words: Rather than relying on political professionals to deliver their message, CHPA got voters to do it—and politicians listened, in Kentucky and beyond. There has been no major federal legislation to address meth labs since 2005, when pseudoephedrine was put behind the counter and sales limits were imposed (see “The Need for Speed,” page 37). Lawmakers in 24 states have tried to pass prescription bills since 2009. In 23 of them, they failed.

The single exception was Mississippi, where a prescription measure supported by Republican Gov. Haley Barbour passed in 2010. The head of the state Bureau of Narcotics, Marshall Fisher, says one key to the bill’s passage was making sure it was not referred to the Legislature’s health committee, where members tend to develop close relationships with pharma lobbyists. Fisher has testified about prescription bills before health committees in several other states. “It seems like every time we’ve done that, the deck is stacked against us,” he says. “You can’t fight that.” Following the bill’s passage, the number of meth labs busted in Mississippi fell more than 70 percent. The state narcotics bureau, which tracks the number of drug-endangered children, reported the number of such cases fell 81 percent in the first year the law was in effect.

Everywhere else, industry has prevailed. Many states have very limited laws on what lobbyists must report, and they don’t monitor spending on robocalls or ads. But news reports and my interviews with legislators in Southeastern and Midwestern states where meth labs are most concentrated—and where CHPA had the biggest fight on its hands—show that the pharmaceutical industry deployed a mix of robocalls, print and radio ads, as well as a Facebook page and a website, stopmethnotmeds.com. These states include Alabama, Kansas, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. The media campaign was backed up by each state’s top lobbyists and PR firms.

“They’ll outspend us 100-to-1,” says Alabama state Sen. Roger Bedford, whose prescription bill has failed twice. In Indiana, which consistently ranks among the top states for meth labs, prescription bills have been defeated five years running. “I met a lot of resistance by the over-the-counter drug manufacturers,” says former Indiana state Rep. Trent Van Haaften. “They were concerned about market share.” In West Virginia, a prescription bill almost made it to the governor’s desk in 2011, when it passed the House but ended up with a tie in the Senate.

In North Carolina, CHPA bought newspaper ads in Raleigh and Charlotte to defeat a 2011 prescription bill. Its sponsor, Craig Horn, was taken aback by the vitriolic calls he got. “Big Pharma has a lot of influence,” he says. “They suggested that making pseudoephedrine-containing medication prescription-only would create a hardship on consumers, [and] that it would cost the state millions of dollars in Medicaid money.” North Carolina saw dramatic increases in meth lab discoveries in 2011 and 2012.

In Oklahoma, state Rep. Ben Sherrer sponsored prescription bills in 2011 and 2012. The first bill got out of committee but never came up for a vote on the floor. “I was told by the pharmaceutical industry it was going to be killed,” Sherrer says. “They had a very brisk media campaign—radio, some large ads in the two major newspapers.” He likens CHPA’s messaging on pseudoephedrine to the tactics of the gun lobby: “The ‘stop meth, not meds’ campaign—it’s sexy in the same way that we see a passionate plea to people who own weapons that they are coming for your guns.”

Detective Jason Back is one of two full-time narcotics officers in Laurel County, a stretch of hills and farms that boasts the site of Colonel Sanders’ original Kentucky Fried Chicken. With his tight black “I ♥ LA” shirt, Back stands out from his colleagues in their beige uniforms. Below a well-worn ball cap, he’s got several days of stubble. A camouflage pistol grip sticks out of his jeans.

In Back’s cramped office, a big flat-screen TV is perched incongruously in a corner. It was confiscated from a drug dealer, just like the truck Back drives for work. On his desk are two piles of paper with scribbled notes. One contains tips about meth labs, the second about prescription pills.

Like Detective Chris Lyon, Back returned to his hometown after a stint in the military. Both now spend their days putting away men and women they grew up with. “It happens all the time,” Back says. A typical arrest will start with: “Hey, what’s up, how’s your family? Good. How’s yours? All right.” He’s learned to shrug it off. “The people that burn out in law enforcement, that’s a big thing—they take it too personal.” Former Sen. Tom Jensen, the Republican sponsor of the prescription bill, is an attorney who recently represented a family friend’s daughter, arrested for smurfing. Jackie Steele, the commonwealth’s attorney in the county and one of the bill’s major law enforcement backers, has a family member who was sent to jail for having meth precursors.

Back’s boss, Sheriff John Root, beat a crowded field for the Republican nomination by promising to go to war on meth. “When I came into office,” Root says, “about every complaint that we had was meth-related. If we went on a domestic, if we went on a burglary, a theft, if we went to check on a welfare check, you would normally find the meth labs there.”

Busting smurfers is grunt work. At the Walgreens off Highway 192 in London, which until recently sold more pseudoephedrine than any pharmacy in the state, it’s like fishing in a well-stocked pond. “People drive up in a piece of shit car in trashy outfits and they are looking around,” says Back. “One goes in, one goes out, another one comes in and another comes out. Tail ’em, traffic stop ’em—’cause they can’t drive, half of ’em ain’t got licenses, ain’t got insurance, got dead tags.” Faced with a one-to-five-year sentence for buying pseudoephedrine with intent to make meth, some will turn evidence against the cooks and dealers. In the meantime, they often end up in the county jail, an octagonal fortress just a few yards from Back’s office. Unable to make bail—meth tends to rob addicts of everything they have, including the support of loved ones—some remain there, waiting for trial, for as long as a year.

That’s what happened to a man I’ll call Jeff. In 2010, Back arrested him after spotting him driving down Main Street in a car with no windshield. The car was so filthy, searching it left Back with a staph infection. Inside, the officer found Sudafed and ammonium nitrate. Jeff pleaded guilty to possession of drug paraphernalia and served four months in the Laurel County Jail. Six days after his release, Back arrested him again for making meth while raiding a trailer on Love Road, just outside London.

Just three years earlier, Jeff had a good job working construction, which allowed him to pay off his house and spoil his four children. He was married to his middle-school sweetheart. She drove a BMW; he had a Chevy truck. His parents had been addicted to cocaine and he was raised by the state, shuttling from boys’ camps to boys’ homes. Now, the 28-year-old was giving his children the life he never had. Jeff was a fiercely independent, hardworking guy. “I don’t have no family to get me nothing,” he told me. “We worked for everything we had.”

Meth, which makes users feel strong and invincible, fit in perfectly with that ethos. “Everybody around me was using it,” Jeff says. “Friends, people I worked with doing construction work.” So one day he smoked some. He liked it. “It don’t cost much money, and I can work all day long, feel good, come home, mow the grass, play with the kids,” he says. “As you get to like it more and more, you do it more.”

Soon Jeff’s life narrowed down to a single all-consuming quest: getting and staying high. He lost his wife, his kids, his job, his house, his tools, and his truck. He was shot in the face at point-blank range and stabbed while driving, both times by other addicts. By the time Back arrested him, he was drifting from trailer to trailer in Laurel County, welcomed for his skills as a cook. Jeff’s wife found other ways to stay high. “She’s got every guy in town that’s more than willing to give her as much drugs as she wants,” he says. She, too, ended up in the Laurel County Jail. But Jeff has no contact with the woman he calls the love of his life. His greatest wish, he told me, was to be released, get his kids back from his mother-in-law, and be the father he once hoped he could be.

County jailer Jamie Mosley says around 100 of his jail’s approximately 350 inmates are there for meth offenses, and many others are in for crimes committed to support their habit. Prison is not a deterrent for these folks, says commonwealth’s attorney Steele. “You are looking at putting somebody in jail for 20 to 50 years or life, and they are still out cooking.”

One January night in 2012, some 100 people sat around large round tables at the fire hall in London, eating battered fish and fries prepared by the county judge. After dinner, a chaplain in cowboy boots offered a prayer to open the town hall part of the evening. Sheriff Root had invited residents in to vent their concerns. Most wanted to talk about meth and pain pills.

Dwight Larkey, who installs heating and air conditioning systems, asked what was being done about thieves ripping out brand new $1,500 units for $40 worth of copper. Jim Dorn, a semiretired official at the local credit union, was upset about news that seven churches had been burglarized in one night the week before. Another man worried about thieves who prey on old people, often going straight for their medicine cabinets in hopes of finding cold meds or Oxy.

Then Steele took the stage. Laurel County led the state in meth labs, he said. “Not coincidentally, we are also No. 1 for the sale of pseudoephedrine.” Make your voices heard in Frankfort, he urged the audience.

A lanky man with spiky hair and glasses, Steele is part of a group of public officials who have taken the lead in pushing for a prescription bill. They couldn’t afford robocalls or big ad buys—last year they raised about $10,000, enough to put ads on a dozen radio stations and set up a website. Still, they had hopes that Belcher and Jensen’s third run at legislation would be the charm.

But CHPA was ready for them. The group began running ads two and a half weeks before the Legislature reconvened, up to 12 times a day in the state’s major markets. The association also hired two Kentucky PR firms, Peritus and BK Public Affairs; Peritus handed the job to Karl Rove’s former deputy, Scott Jennings. CHPA would end up setting a new Kentucky lobbying record that session, spending almost a half million dollars, three and a half times more than the next biggest spender. Most of the money went to robocalls.

In public, the task of defending CHPA’s argument against prescription bills falls to Carlos Gutierrez. A slight man with graying temples, the Texas native joined CHPA in 2010 as its head of state government affairs and since then has crisscrossed the nation putting out fires for the industry.

Gutierrez disputes the effectiveness of the prescription approach. He points out that meth labs began to drop in Oregon even before that state’s law took effect. He notes that states bordering Oregon and some of Mississippi’s neighbors have also seen large declines in meth labs. (A US Government Accountability Office study released in February found that those declines were due in part to cuts in federal meth lab cleanup funds. It said the drop in labs in Oregon was strongly correlated to the prescription bill’s passage.)

Gutierrez also notes that having to get a prescription makes pseudoephedrine drugs more expensive to consumers, and that most meth in the United States still comes from Mexico. (Drug enforcement officials confirmed this, though none could give me an estimate of how much meth is domestically produced; some noted that locally cooked meth is often dominant in rural areas.)

When testifying before lawmakers, Gutierrez says the industry is committed to preventing medicines from being diverted into the drug trade: “We’ve invested, frankly, millions of dollars into systems to prevent diversion,” he said during a hearing in Kentucky. He was referring to a tracking system the industry underwrites, the National Precursor Log Exchange, which logs pseudoephedrine sales in 25 states (some retailers, including Rite Aid and CVS, have also installed it in stores nationwide). The system, known as NPLEx, blocks customers from buying pseudoephedrine once they reach the limit set by each state’s laws. Police can also access sales information to look for suspicious purchases. Gutierrez touts NPLEx as an alternative to prescription bills, though the GAO report found the system has not reduced labs because cooks are still finding ways to smurf.

What Gutierrez doesn’t tell legislators is that CHPA vigorously fought the federal law NPLEx is designed to enforce, the 2005 Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act, just as it has regularly fought attempts to control the chemicals used to make meth since the 1980s. In 2004, CHPA’s then-president, Linda Suydam—a 21-year Food and Drug Administration veteran—personally argued against the 2005 bill, saying it would “have a greater impact on sick kids, caregivers, and flu sufferers than on criminals.”

Today, though, pharmaceutical companies use the NPLEx system as one of their top arguments in fighting new regulation—including in Washington, where they have managed to keep a lid on any discussion of a federal prescription bill. “Honestly, because industry’s pull in Congress is so strong,” one Hill aide told me, “every time we would schedule a meeting or do anything, anybody who got wind of it would have a meeting with someone from the pharmaceutical industry. They got scared of it.”

When I called CHPA spokeswoman Emily Skor, she said: “It really comes down to balancing what is the best way to stop criminal activity while enabling consumers to buy the medicines when and where they need them. That sums up our overall approach through time.”

Kentucky was the first state to adopt the NPLEx system—it was piloted in Laurel County. “We wanted it to work,” says Dan Smoot, the vice president of a drug enforcement and prevention organization called Operation UNITE who helped implement NPLEx in southeastern Kentucky. But the number of meth labs has tripled in Kentucky since NPLEx went into effect across the state in 2008. Nationwide, many states that adopted NPLEx have also seen their meth lab numbers increase. (Advocates for NPLEx say this is because the tracking system is helping police find more of them.) Today Smoot is one of the major law enforcement backers of prescription legislation.

Rob Bovett has a lot of sympathy for Kentucky. “They are in that same position” Oregon law enforcement was in a decade ago, he says: “They are frustrated. They want real solutions. They’ve tried things that haven’t worked; they’ve bought the industry’s line. They are done with that.”

In 2012, Belcher introduced her bill once again. When it went before the House Judiciary Committee, chairman John Tilley estimates he received more than 1,000 calls, emails, and letters. Most came from the major media markets of Louisville and Lexington, not his constituents.

In the end, the Legislature passed an industry-approved measure that barred people with prior drug offenses from buying pseudoephedrine for five years. Despite stiff opposition from CHPA, lawmakers also included reductions in the maximum amount of pseudoephedrine Kentuckians can purchase—limits that law enforcement says have halted the three-year run of record-breaking meth lab numbers in the state. Kentucky finished 2012 with 1,060 meth labs, the fourth most in the nation.

Amanda’s teen years were upended by her parents’ meth arrest. Her father was sent to a federal prison in northern West Virginia for two and a half years. Her mother spent six months in jail on a lesser charge. At school ugly rumors spread, and soon Amanda dropped out. She and her sister stayed with their ailing grandparents, who died while the girls’ father was still in jail.

After being released from jail, Mary went to rehab, and eventually Barry came home and found work at a car wash. Today, Amanda is back in the family home. When I visited, her mother cooed over Amanda’s new baby, Logan, while at the front of the trailer, Amanda and her husband, Joey, showed off their new bedroom—teal walls, a queen bed, a crib in the corner. You wouldn’t know it, but this was where Amanda’s parents cooked meth. Barry still has a hard time talking about the events that tore his family apart. “It usually ends up with Dad about to cry,” says Amanda.

But the pain of separation has brought the family closer. That’s why Barry and Joey spent two weeks fixing up that bedroom, once corroded and filled with junk. They tore the walls down to the studs and put in all new carpet and drywall. “They don’t want me to leave,” Amanda says.

This story was supported by the Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute.