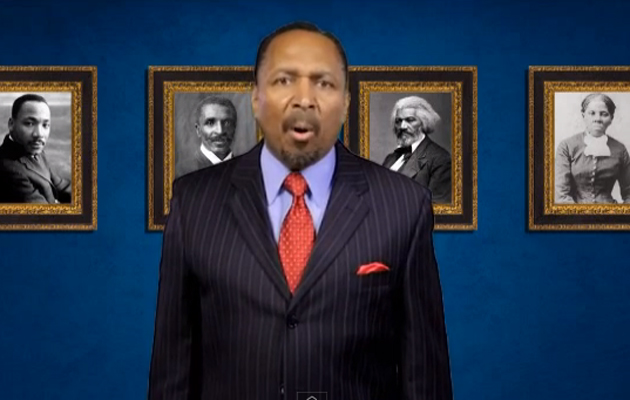

E.W. Jackson/YouTube

Last October, appearing on a radio show hosted by Americans for Truth About Homosexuality founder Peter LaBarbera, the Rev. E.W. Jackson lobbed the kind of incendiary device that has become his forte. By sanctioning homosexuality (which he associated with AIDS), Jackson alleged liberals had “done more to kill black folks whom they claim so much to love than the Ku Klux Klan, lynching and slavery and Jim Crow ever did.”

Jackson, the Republican nomination for lieutenant governor of Virginia, has quickly established himself as a uniquely polarizing politician. But when it comes to AIDS, Jackson has backed up his words with action. As an activist in Boston in the late 1980s and early ’90s, Jackson worked tirelessly to defeat programs designed to curb HIV transmissions and save lives. In his view, the only sure-fire way out of the AIDS crisis was abstinence; everything else simply encouraged the kind of immoral behavior he was against.

In 1987, as federal and local officials were first beginning to take preventative efforts, Jackson organized a group of 30 clergymen in opposition to a proposal from Boston’s superintendent of schools to place four public health clinics in city schools. He claimed any program that even mentioned condoms was promoting promiscuity. That same year, he held a candlelight vigil outside a local ABC affiliate, WCVB, demanding that the station pull sex education public-service advertisements that endorsed the use of condoms. As the Associated Press reported at the time, “Jackson said the commercial showed a 10- to 12-year-old girl saying, ‘I just learned to have safe sex.'” (The girl was actually either 16 or 17, according to the ad’s creator.)

He hardly mellowed with age. In 1990, after anti-AIDS activists like ACT UP had won a hard-won victory to get the state to launch a public education campaign, Jackson held a press conference to condemn Massachusetts Human Services Secretary Philip Johnston’s decision to promote condom use as a means of reducing the risk of HIV infection. “What will they do next?” Jackson asked, “give condoms to children instead of lollipops?”

His anti-anti-AIDS crusade extended beyond issues of abstinence and sex ed. In the early 1990s, Jackson helped lead the fight the against Boston Mayor Ray Flynn’s efforts to combat the spread of AIDS among drug users. Flynn proposed a program that would allow addicts to swap old, dirty needles for new, sterile ones at select centers across the city, without fear of prosecution.

The AIDS activism was part of Jackson’s larger campaign against the forces of immorality. Jackson’s years in Massachusetts were defined by an endless series of protests and controversies. At his most high-profile, he lobbied the state Legislature to block same-sex couples from becoming foster parents. He vowed to blast “to smithereens” a bill granting anti-discrimination protections to gays and lesbians. “If we need a gay rights bill, then we need an adulterers’ rights bill, we need a cohabitators’ rights bill, a pedophiles’ rights bill, and a sadomasochists’ rights bill,” Jackson said at the time.

“A reasonable person back then could’ve been opposed to the bill—it was the ’80s!” recalls Arline Isaacson, an LGBT lobbyist who clashed with Jackson on the nondiscrimination law. “People were less comfortable with gay folks back then, but there were clearly gradations of opposition, and Rev. Earl took the far-right over-the-top crazy opposition.”

During these years, Jackson appeared to always be on the hunt for a new front in his war on immorality. A 1988 Boston Globe piece featured Jackson among 70 protesters marching in circles outside Aga’s Highland Tap, a Roxbury strip club, which they hoped to shut down. A judge ruled that the club could stay open. “We are already beset by drugs, violence, crime,” he told the Globe. “We don’t need another negative element added to the mix.”

And when a local news anchor, Liz Walker, announced on air that she would have a child out of wedlock, Jackson channeled Dan Quayle. “At a time when we struggle in our community with teenage pregnancy and unwed motherhood…and we are trying to create proper values, this is precisely the wrong kind of signal to send,” he said. “What she’s doing is wrong.”

Jackson’s biggest platform was the airwaves, not the pulpit. Beginning in the mid-’80s, Jackson owned his own gospel radio station in Boston and hosted a nationally syndicated talk show. As The New Republic reported, Jackson never let his listeners forget where he came from: “the land of the freebies and the home of the gays—Barney Frank and Gerry Studds country.”

“There was a symbiosis because he was using this issue to create stature for himself, garner publicity, and get on TV,” Isaacson recalls. “He would never ever otherwise have found himself into the media market had it not been for his outrageous opposition to” the anti-discrimination bill.”

Jackson closed the book on Boston in 1998, when he moved to Chesapeake, Virginia, to start a new church. But his efforts to block those advances have not been forgotten in a state where gay rights activists have claimed victory after victory.

“When you talk to him,” Isaacson said, just before we hung up, “send him my love.”