At 5:20 a.m. on Monday, four hours before the Boston Marathon’s elite runners took off, a group of 15 active-duty soldiers from the Massachusetts National Guard gathered at the starting line in Hopkinton. Each soldier was in full combat uniform and carried a “ruck,” a military backpack weighing about 40 pounds. The rucks were filled with Camelbacks of water, extra uniforms, Gatorade, changes of socks—and first-aid and trauma kits. It was all just supposed to be symbolic.

“Forced marches” or “humps” are a regular part of military training, brisk walking over tough terrain while carrying gear that could help a soldier survive if stranded alone. These soldiers, participating in “Tough Ruck 2013,” were doing the 26 miles of the Boston Marathon to honor comrades killed in Iraq and Afghanistan, or lost to suicide and PTSD-related accidents after coming home.

It took about eight hours for all of the soldiers to cross the finish line, some cruising nearly at a 13-minute mile, others coming in at a little slower pace. They were gathered near the medical tent behind the finish line, waiting for the elite runners to come in. That was the contingency plan in case anything went wrong—meet by the medical tent.

“You never think you’re gonna need it, but you always have to have a contingency plan,” says Lieutenant Stephen Fiola of the 1060th Transportation Company, who worked with the Military Friends Foundation to organize the march. Two soldiers stationed in Afghanistan also participated in the ruck from afar, according to Fiola, marching in circles around their base for 26 miles in remembrance of fallen comrades.

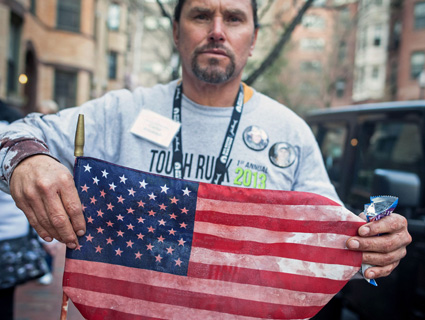

One soldier in the Boston group walked the marathon in honor of Lance Cpl. Alexander Arredondo, who was 20 years old when he died in action in Iraq in 2004. Arredondo’s father, Carlos, was waiting at the finish line to greet the ruckers, wearing a cowboy hat and a Tough Ruck T-shirt, and carrying pictures of his two deceased sons, the second of whom succumbed to depression and suicide after his brother was killed. Fiola was also there, handing Arredondo a bunch of small American flags to pass out to the crowd of spectators in the bleachers. “Everyone was so happy,” says Fiola. “People were cheering, there was music playing, it was almost a surreal experience. A beautiful day.”

When the explosion went off, Fiola and his group immediately went into tactical mode. “I did a count and told the younger soldiers to stay put,” Fiola says. “Myself and two other soldiers, my top two guys in my normal unit, crossed the street about 100 yards to the metal scaffoldings holding up the row of flags. We just absolutely annihilated the fence and pulled it back so we could see the victims underneath. The doctors and nurses from the medical tent were on the scene in under a minute. We were pulling burning debris off of people so that the medical personnel could get to them and begin triage.”

Once the victims were transported away for further medical care, Fiola and the others stood guard around the blast area. “We switched to keeping the scene safe, quarantining the area and preventing people from entering. There was a guy behind me covered, just covered, in his own blood, and I started to smell some smoke. I turn around to look and he’s actually on fire, from a piece of whatever caused the explosion. I saw the smoke coming from his pocket so I reached in and pulled it out. It was his handkerchief, on fire.”

Fiola saw Carlos Arredondo in the distance, assisting more victims. One of Monday’s most harrowing images shows Arredondo, with his cowboy hat and long dark hair, and two others frantically wheeling a young man who appeared to have lost parts of both his legs.

In a video shot by a bystander moments later, Arredondo trembles visibly and grips one of the American flags Fiola had handed to him, now drenched in blood, and explains what he saw and did after the explosions. The right sleeve of his Tough Ruck T-shirt is crimson up to the elbow.

On Tuesday, Fiola said his priority is checking in on the members of Tough Ruck 2013, asking how they’re doing in the aftermath of the tragedy and getting them connected with the Massachusetts National Guard’s support system of mental-health providers, chaplains, and fellow soldiers. He’s encouraging them to talk about what happened with a focus on the help they were able to provide during the chaos.

“We had some sort of an influence, at least in helping the nurses get to the wounded and helping calm people down,” he says. “It’s one of those things that makes you go home and kiss everyone in your family.”