Tipping the scalesMaggie Caldwell/Photo Illustration; Photos from <a href="http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6e/Brass_scales_with_cupped_trays.png">Wikimedia Commons</a>, <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/46183897@N00/5235994270/">Gurdonark</a>/Flickr

In 2012, Rep. Ander Crenshaw (R-Fla.) and his colleagues in the Republican-led House of Representatives put forward a record number of legislative items that would directly impact the environment for good or ill—but mostly for ill. The acts ranged from mandating drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to defunding the federal government’s efforts to prohibit use of fuels that emit high levels of greenhouses gases to completely gutting the Clean Air Act. Out of the more than 100 bills, riders, and amendments advanced by the House, the League of Conservation Voters in its 2012 Congressional Scorecard highlighted 35 bills that had the greatest ramifications for the environment and public health. On those 35 bills, Crenshaw voted against the environment 33 times.

It might not seem that surprising considering Republicans’ record on conservation initiatives in recent years is spotty at best, but Crenshaw sits as one of the chairmen of a group of 140 lawmakers* who joined together to advance initiatives for the protection of natural resources around the world: the International Conservation Caucus.

The ICC is the congressional arm of the International Conservation Caucus Foundation, a group that takes a “Teddy Roosevelt approach” to environmentalism, which its founders define as protecting natural resources while also pursuing ways to extract their greatest potential for the profit of mankind. (Corbin Hiar, a former Mother Jones intern, wrote about the foundation in the March/April issue. His story was published online this morning.) In doing so, the ICCF makes strange bedfellows out of organizations such as the Nature Conservancy and ExxonMobil.

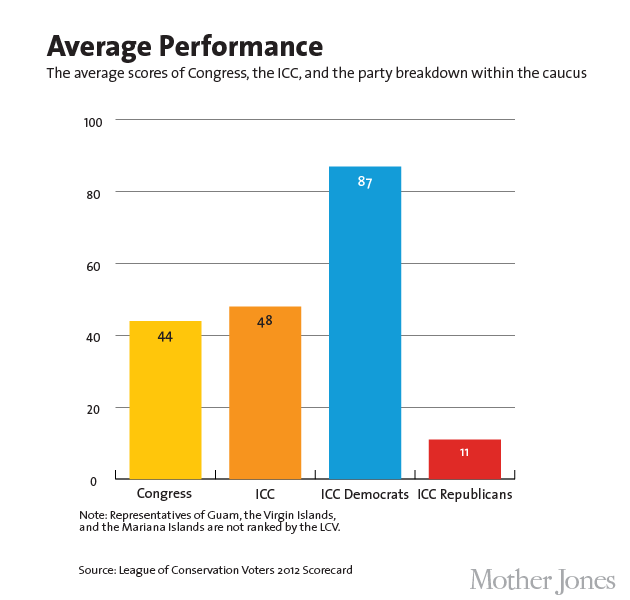

Every year since 1970, the LCV has released a scorecard for members of Congress rating their voting record on important environmental legislation on a scale of 0-100. The voting records from 2012 show that members of the ICC were slightly more ecofriendly than members of congress on whole, but that’s not saying much. Congress averaged a score of 44 on the LCV spectrum. Members of the ICC averaged a score of 48, voting against the environment more than half the time.

But the averages don’t paint the whole picture. Democratic members of the caucus increase its average score (or, if you’re a glass-half-empty kind of person, the Republicans drag the average down). Democrats in the ICC are only slightly more environmentally friendly on average than congressional Democrats, with average scores of 87 and 83, respectively. For Republicans, being in or out of the caucus makes little difference. Republican members of the ICC and Republicans as a whole both have average LCV scores of 11.

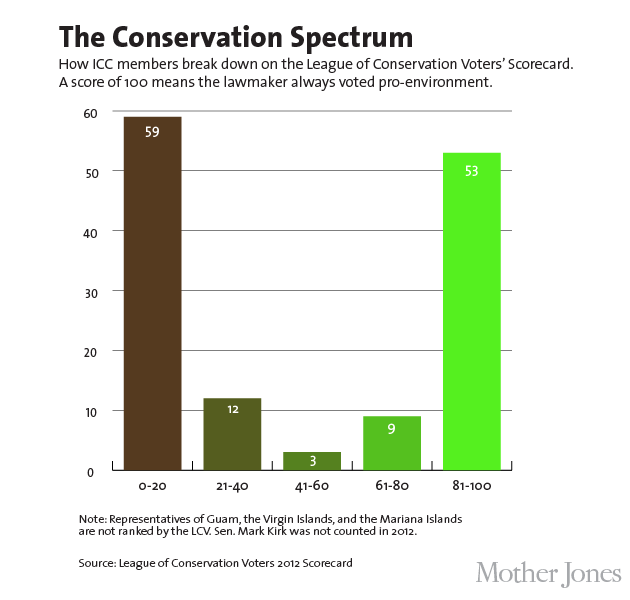

The ICC has a truly mixed bag of partners on Capitol Hill, counting among its members environmental champions like Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) who scored 93, and then those like Rep. Crenshaw who, along with 40 others members of the ICC, received scores of 10 or less, including Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), who scored a big, fat goose egg.

There’s very little middle ground on the conservation spectrum. You’re either with the environment or against it. But what is the point of a conservation caucus that includes many members whose voting records show they directly oppose the basic tenets of the organization?

Maybe it’s the little victories that count.

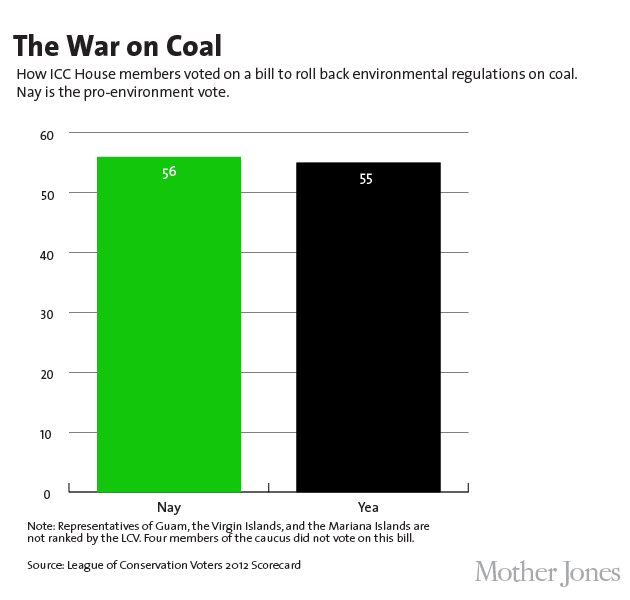

One vote that tested the whole Teddy Roosevelt school of conservation was the House’s so-called Stop the War on Coal Act of 2012. The act, advanced by House Republicans, was an attempt at rolling back fundamental environmental protections to open up streams and waterways to coal mining. It was meant to deregulate the industry by limiting the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, halting Clean Air Act protections, and gutting the core of the Clean Water Act. The LCV called the bill a “broad environmental assault.”

The House members of the ICC were nearly evenly divided over the vote with 56 voting against it and 55 voting for it (with four abstentions).

The Teddy Roosevelt approach, it would seem, is open to some interpretation. Although the 26th president brought nearly 230 million acres of land under federal protection during his time in office, half the members of a caucus working in his name are trying to undo many of those same protections.

There is an additional member of the caucus who is a chaplain, bringing the total to 141, but he is not counted in the charts because he is not a voting member. Return to text