<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/francois_michonneau/">francois.michonneau</a>/Flickr

Update (9/7/12): Another person was confirmed to have died from hantavirus after spending time in Yosemite, bringing the death toll to three and infection count to eight. And in a pattern shift for the outbreak, a man who had recently stayed in the High Sierra Camps in Yosemite tested positive for the virus, so officials widened the scope of the potential outbreak to include areas outside of the Curry Village tent cabins and now believe that 22,000 park visitors might have been exposed over the summer.

Whenever I stay in backcountry huts in Northern California’s Sierra mountains, I fight back paranoia spurred by posted signs describing the ominous hantavirus, a rare but deadly sickness spread by rodents who nest in cabins and congregate around likely sources of food and shelter. This year, my paranoia is even more founded: Two people have died and four more are recovering from the virus in what’s being described as an unprecedented outbreak this summer in Yosemite. Park officials have traced the cases back to a cushy tent compound called Curry Village where those afflicted stayed at some point over the summer, and have alerted 3,000 visitors via email of potential exposure to the virus.

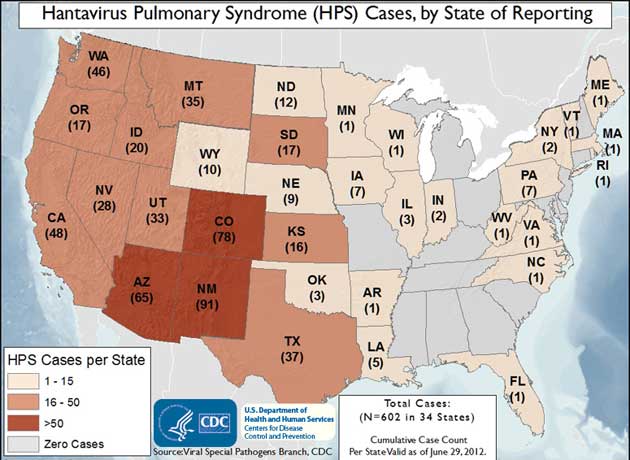

US wilderness outfits and public health officials have been warning about hantavirus for years, ever since an outbreak of the “Sin Nombre” virus, a type of hantavirus, was newly identified in the Four Corners region of the country in 1993. Since then, 602 cases of hantavirus pulminary disease, the fatal sickness asssociated with the virus, have been reported in 34 states. So why all the fuss about the six confirmed cases in Yosemite?

There are several strains of hantavirus around the world, and a few of them cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), a flu-like respiratory illness that results in death almost 40 percent of the time. The Sin Nombre virus that made headlines in the nineties is carried by deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus), which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls a “deceptively cute animal, with big eyes and ears.” They live pretty much all over the US, mostly in woodlands or deserts but sometimes in urban areas. “There have been deer mice found in even Washington, DC and New York City,” Yosemite National Park spokesperson Kari Cobb tells me. Contact with a deer mouse’s fresh urine, feces, or saliva causes the virus to spread to humans, commonly through the inhalation of dust particles that have mixed with animal feces. This tends to happen in rural buildings like barns, cabins, and sheds–where deer mice nest and might poop.

There’s no cure and no virus-specific treatment for the illness, so public health officials just warn people to avoid rodents and thoroughly clean areas where these animals nest. And even though 15-20 percent of deer mice are infected with hantavirus, Cobb explains, it’s a rare disease for humans to contract, mostly because the virus dies shortly after contact with sunlight, and it can’t spread from one person to another. HPS is more prevalent in the Southwest, but over half of all cases have occurred elsewhere, mostly in rural areas.

The fact that three to four people came down with HPS after staying in one specific location makes the Yosemite outbreak rather unusual. “Usually it’s random and happens in different places and doesn’t affect multiple people in the same place,” Cobb says. The sudden uptick has park visitors pretty freaked. Once Yosemite established a hantavirus hotline last Tuesday, 700 people called to inquire about possible exposure and symptoms within 24 hours, reports ABC News. Meanwhile, the park has launched an investigation into the deer mouse population and percentage of mice carrying the virus in order to try and figure out why so many people may have contracted the illness.

I wondered whether changes in climate could have expanded the deer mouse population and therefore incidence of hantavirus. “Usually it’s the wetter years that affect the mice and make populations increase,” says Cobb. This year was actually pretty dry in Yosemite, with only 50 percent of normal snowpack. But, Cobb adds, “last year we had a 200 percent increase in snowpack.” Potentially, a wetter 2011 may have caused deer mice colonies to grow. This scenario would mirror events described in a recent study out of the University of Utah, which mentions that increased precipitation from El Niño two to three years prior was to blame for more dense deer mouse populations in the Southwest around the time of the 1993 Sin Nombre outbreak.

Janet Foley, an epidemiologist at University of California-Davis who examines how changes in biodiversity and climate impact infectious diseases, says that the deer mouse is a very common mammal no matter the weather. But she questions what might be making the mouse become more of a pest: “Is it need for more access to a food source?” The drought this year has caused bears to become a huge hassle as they seek food; maybe the mice are also more likely to search for vittles in human shelters, Foley posits. “Everything that affects the ecology of the deer mouse could affect hantavirus,” she says.

There’s some indication that a changing climate could affect incidence of the virus. A 2009 study by a Slovakian virologist found that higher temperatures in Western and Central Europe have been associated with more frequent hantavirus outbreaks as vole populations increase (though voles carry Puumala hantavirus, not Sin Nombre). The Utah study mentioned above reasons that El Niño and climate change “enhance hantavirus prevalence when host population dynamics are driven by food availability.” But the paper also attributes increases in hantavirus to human disturbances to the land in areas like farms (or touristy tent cabins) where human traffic increases a deer mouse’s access to food. Climate change affects hantavirus patterns, the Utah researchers claim, though the changes vary depending on location, rodent species, and landscape alterations, and it’s still a little early to predict what might happen with hantavirus over the next few decades as tools to diagnose the illness have only been around for 15 years or so. Researcher Denise Dearing, who co-wrote the Utah study, tells me that after eleven years of collecting data, unfortunately funding for her hantavirus study was cut last year; as she sees it, the virus will be unpredictable “unless we have a large surveillance set up” to continue studying the disease.

The hantavirus warning posters I’ll confront next time I’m in the Sierra backcountry huts will likely continue to give me the heebie jeebies. And speaking of warning signs, Yosemite never posted any in its tent cabins; the park is now under fire for allegedly neglecting to heed warnings from California public health scientists to educate visitors about the disease, a California Watch investigation discovered. Indeed, Cobb told me there were no signs hanging in Curry Village before the outbreak. “It is just so rare, there were no known cases in Yosemite Valley before this,” she said, though there were two known cases linked to Tuolumne Meadows nearby. Now the park has closed an area of Curry Village indefinitely, and plans to be pretty agro about passing out pamphlets and training employees on safe ways to clean cabins and avoid contamination; as well it should, if you consider Slovakian researcher Boris Klempa’s 2009 warning that “hantaviruses will undoubtedly remain a significant public health threat for several decades to come.”