When Lynn Raskin googled Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown, she ended up clicking on an ad for Republican Senator Scott Brown. Screenshot: GoogleLynn Raskin, a Washington D.C. realtor, and her husband, Marcus, a cofounder of the Institute for Policy Studies, have routinely contributed to progressive candidates in tight congressional races during this election cycle. They’ve donated to Rep. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisc.), Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.), and Elizabeth Warren, the Democrat running for Senate in Massachusetts. They’ve also given money to Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio).

When Lynn Raskin googled Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown, she ended up clicking on an ad for Republican Senator Scott Brown. Screenshot: GoogleLynn Raskin, a Washington D.C. realtor, and her husband, Marcus, a cofounder of the Institute for Policy Studies, have routinely contributed to progressive candidates in tight congressional races during this election cycle. They’ve donated to Rep. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisc.), Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.), and Elizabeth Warren, the Democrat running for Senate in Massachusetts. They’ve also given money to Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio).

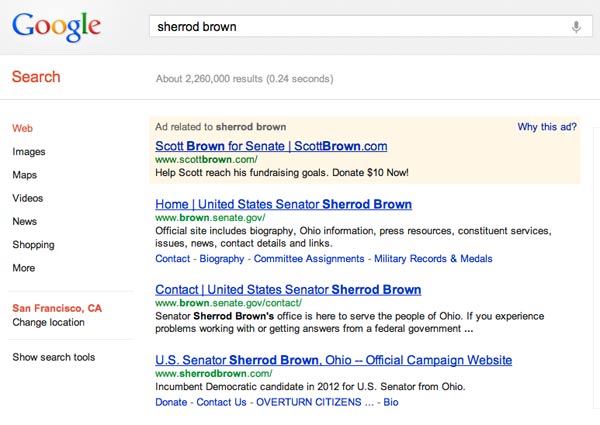

Late Saturday evening, Raskin typed “Sherrod Brown” into Google to make another campaign contribution. She clicked the first link populating her search results, a Google ad that took her to an innocuous-looking campaign fundraising page. She entered her Visa digits, hit submit, and just like that, she’d forked over $50 to a Republican in one of this season’s most hotly contested Senate races: Sen. Scott Brown of Massachusetts.

Raskin realized her mistake the next day when she read the automated thank-you email from Scott Brown’s campaign. She says she takes “full responsibility for not paying attention” when she clicked on Scott Brown’s Google ad, but she still feels like she was duped. After all, why should a search for Sherrod Brown, Ohio Democrat, bring up an ad for Scott Brown, Massachusetts Republican?

When I told Sherrod Brown’s communications director Justin Barasky about Raskin’s story, he says he’d never heard of anything like it before, though it seemed “pretty shady.” Raskin also found it shady. “Obviously, it’s a way to try to get mistaken contributions from people like me who are not paying attention,” Raskin theorizes. “It’s a way to divert money from people who are supporting progressive candidates.”

But is it?

Google’s algorithms, not a sneaky Scott Brown operative, are likely to blame. Scott Brown spokesperson Alleigh Marré says that the campaign did not pay to have the keyword phrase “Sherrod Brown” trigger its Google ads. She declined to comment further on the campaign’s online strategy.

But Clay Schossow, a cofounder of web-development firm New Media Campaigns, has a pretty good idea of what happened. “You can see where the mix up is,” Schossow says. “They both have the same last name and the same first letter of their first name…As someone who has been there, I have seen our political clients get traffic to their website based on specific terms we don’t want to target.”

That’s because most advertisers who sign up for AdWords, Google’s flagship pay-per-click advertising platform, target specific keywords (e.g. “Scott Brown”) and allow Google to run their ads around searches loosely related to those words (e.g. “Massachusetts senator”) in order to reach as many eyes as possible. AdWords uses a sophisticated algorithm to match ads with search terms based on the amount of money advertisers are willing to spend, as well as the ads’ relevance to users’ searches. But the Google gods aren’t infallible, so not all queries generate pertinent ads, as Schossow pointed out. It’s important, he says, for advertisers “to keep a close eye on what terms they’re paying for and how those terms are converting folks.”

On Tuesday, a Scott Brown ad popped up when I googled “Sherrod Brown.” (See image above.) But as of yesterday, a search for Sherrod Brown no longer called up a Scott Brown ad.

Scott Brown’s use of Google ads is not new. In his 2010 Senate bid, Brown, a long-shot candidate with a shoestring budget, defeated state Attorney General Martha Coakley in part because he ran “one of the most aggressive” Google AdWords campaigns ever. The Scott campaign reportedly used AdWords to reach users searching for both his and Coakley’s names. So impressed was Google that the search engine behemoth invited Brown’s chief web strategist to give a talk at its Washington, D.C. headquarters.

Ordinarily, online ads funded by political candidates must state that they’ve been paid for by the candidate. Two years ago, the Federal Election Commission voted to permit Google to run short text-based politcal ads without disclaimers. However, there’s nothing about the Scott Brown ad that suggests it might be an ad for another candidate.

In the aftermath of the mix-up, the Scott Brown campaign has issued Raskin a full refund and she has donated successfully to her preferred Sen. Brown.