Courtesy of the Sangji family

Sheri Sangji was on fire instantly. The 23-year-old research associate had accidentally pulled the plunger out of a syringe while conducting an experiment in a UCLA laboratory. In the syringe was a solution that would combust upon contact with air. It spilled onto Sangji’s hands and body.

She wasn’t wearing a lab coat; no one had told her to. The fire burned through her gloves, then her hands. She inhaled toxic, superheated gases given off by her burning polyester sweater, a process that accelerated as she ran and screamed.

It was the afternoon of December 29, 2008. Campus was mostly quiet for the holidays, but chemistry professor Patrick Harran’s team was at work. He was in his office, one floor up from Room 4221 of the Molecular Sciences Building, where at his direction Sangji had been trying to produce a chemical that held promise as an appetite suppressant. She was unsupervised.

Two postdoctoral fellows were nearby when Sangji caught fire. One ran upstairs to summon Harran; the other tried to smother the fire with his lab coat. He didn’t think to put Sangji under an emergency shower a few feet away. By now, deep burns covered almost half her body.

Harran found Sangji “sitting on the floor,” her clothes “either caked to her or burned off,” he later told an investigator. Eighteen days later, on January 16, 2009, Sangji died from her wounds.

“Sheri was a young girl who was working in a laboratory in one of the largest and most prestigious universities in the world,” says Sangji’s older sister, Naveen, now a surgical resident in Boston. “There should be no safer place for someone to go to work. Instead, she never got to come back home.”

An unprecedented prosecution

In December 2011, the Los Angeles County district attorney filed a criminal complaint against Harran and the regents of the University of California alleging “willful violation of an occupational safety and health standard causing the death of an employee”—the first time an American university professor had been accused of a felony in connection with the death of a worker.

On Friday, the criminal case against the university regents was dropped after they agreed to establish a $500,000 scholarship fund in Sangji’s name at the University of California-Berkeley. They also promised to implement new safety measures, including requiring all of UCLA’s principal investigators, such as Harran, and their lab employees to complete a safety training program within 60 days. The criminal case against Harran, who faces up to 4 1/2 years in jail, continues; his arraignment was postponed until September 5.

But Sangji’s death has had effects far beyond those court cases. Faculty members, department heads and deans across the country have followed the developments with consternation: Might they, too, be criminally liable if something happened in one of their labs? “The district attorney got the attention of every research institution in the United States,” says Harry Elston, editor of the Journal of Chemical Health and Safety.

Harran, 42, did not respond to interview requests from the Center for Public Integrity and the Center for Investigative Reporting. In a 2009 statement to the Los Angeles Times, he called Sangji’s death a “tragic accident” and explained, “Sheri was an experienced chemist and published researcher who exuded confidence and had performed this experiment before in my lab. Sheri had previous experience handling pyrophorics, chemicals that burn upon exposure to air, even before she arrived at UCLA…However, it seems evident, based on mistakes investigators tell us were made that day, I underestimated her understanding of the care necessary when working with such materials.”

UCLA officials declined interview requests, pointing to a written statement issued by university Chancellor Gene Block in January. “Sheri Sangji’s death was strongly felt by everyone at UCLA, and we were deeply saddened by the loss of a member of our community,” Block wrote. “I made a pledge then that we would go above and beyond existing policies and regulations to become a model of campus safety. And we have.”

Documents used to build the criminal case against Harran and the regents paint a vivid picture of the events leading up to the accident at UCLA. And investigations undertaken since Sangji’s death raise questions about safety at academic laboratories across the country. The American Chemical Society, a professional association for chemists, recently unveiled a draft report recommending ways to change the “safety culture” in academia, where labs are stocked with students and other young workers. The study, its authors wrote, was prompted by “devastating incidents in academic laboratories and observations, by many, that university and college graduates do not have strong safety skills.” Last fall, following a serious 2010 accident at Texas Tech University, the US Chemical Safety Board released a report stating that it was “greatly concerned” by the frequency of such accidents. The board said it had documented 120 in university labs since 2001, and identified “safety gaps” that threatened more than 110,000 graduate students and postdoctoral researchers in the US.

“A scientist’s scientist”

Sheri Sangji was raised in Karachi, Pakistan, and graduated from Pomona College in Southern California in May 2008. A superior student and athlete, she earned a degree in chemistry but had no plans to make a career in the field. “She was a very dynamic person with lots of interests, a lot of spark,” says her sister Naveen, 29, also a Pomona graduate. “She was interested in the environment, women’s rights, minorities’ rights.”

Sheri took a job with a pharmaceutical company outside of Los Angeles, hoping to save money for law school. She was intrigued by an ad Harran placed for a research associate at UCLA. The idea of working for a “rising star” in organic chemistry appealed to her, Naveen says.

When Sangji interviewed for the job in September 2008, Harran was impressed. Sangji “was very familiar with analytical instrumentation of the type that I really wanted her to focus on, which was great,” Harran later told Brian Baudendistel, who investigated the accident for California’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA). “I asked her if she was comfortable with general techniques and properties of organic chemistry. And I asked her if she worked with air-sensitive materials…Just how generally comfortable she was in the laboratory. That’s what we spent most of our time on, and she left. And, you know, I loved her. I thought she was fabulous.”

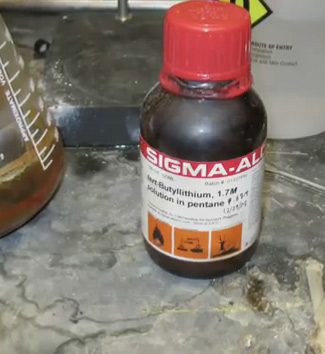

Sangji began work on October 13. Four days later, Harran watched her perform a small-scale experiment using tert-Butyllithium solution, a chemical its manufacturer, Sigma-Aldrich, describes as follows: “Reacts violently with water. Contact with water liberates extremely flammable gases. Spontaneously flammable in air. Causes burns.”

Sangji did a “great job” on the experiment, Harran told Baudendistel, and had knowledge of chemistry beyond her years. “She had published in top peer-reviewed journals with very well-known researchers…She stood out.” Harran acknowledged, however, that Sangji did not receive generalized safety training. “I believe my assistant told me that it was not offered for her category per se, although we were going to follow up on that.” He also said that no fire-resistant clothing was available to lab employees at the time of the accident.

Harran had been recruited to UCLA from the University of Texas-Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, where he’d spent nearly 11 years and won a number of honors. According to Steven McKnight, chairman of the biochemistry department at UT Southwestern, Harran “built a very strong laboratory and proceeded to make a number of really nice discoveries in the field of synthetic chemistry.” Harran and a colleague, Xiaodong Wang, developed a chemical that causes cancer cells to kill themselves. They published a paper on the breakthrough in Science magazine.

A graduate of Skidmore College and Yale, Harran was “a scientist’s scientist,” McKnight says. “He really wanted to dig in and make discoveries of consequence. When he went to UCLA it was a heartbreaker.”

A violent reaction

UCLA pursued Harran aggressively, offering him a budget of $3.2 million to set up a state-of-the-art organic chemistry lab on the fifth floor of the Molecular Sciences Building. He and his team were given temporary space on the fourth floor while renovations were made upstairs.

On October 30, 2008, UCLA chemical safety officer Michael Wheatley conducted an annual inspection of the fourth-floor labs. Wheatley found a number of deficiencies, one particularly relevant to events that would soon unfold: “Eye protection, nitrile [synthetic rubber] gloves and lab coats were not worn by laboratory personnel.”

In an email on November 5, Wheatley asked Harran when they could meet to discuss the findings. “Is it possible to wait until we get settled on the 5th floor?” Harran replied a week later. “That would make for a better meeting—our labs on 4 are overcrowded and disorganized. I wasn’t planning to be in temporary space for this long.” Wheatley agreed to the delay.

On December 29, a Monday, Sheri Sangji reported for work on the fourth floor. Harran wanted her to replicate a chemical reaction she’d performed on October 17, but on a scale three times larger. Around 1 p.m., Sangji was using a 60-millileter plastic syringe with a 2-inch needle to transfer tert-Butyllithium from a bottle. The bottle Sangji held during the accident CPI

The bottle Sangji held during the accident CPI

The needle was too short; the manufacturer recommends using one at least a foot long. Cal/OSHA’s Baudendistel theorized that the smaller needle forced Sangji to tilt or lay the bottle on its side, awkwardly withdrawing the liquid with one hand while holding the bottle with the other. Had the needle been long enough, she could have clamped the bottle, upright, to the workbench, a less risky procedure. Safer still would have been the “cannula technique,” where an inert gas like nitrogen is used to push a liquid through a tube from one container to another.

Sangji accidentally pulled out the plunger of the syringe, spilling the solution and triggering a flash fire. Had she been wearing a fire-resistant lab coat, her burns might have been less severe. In fact, she was wearing no lab coat, not even a cotton one.

At the time there was no university policy requiring such protection. “That policy has been put in place since the accident,” Harran told Baudendistel. Requisition forms from the UCLA Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry show that fire-resistant lab coats were, in fact, ordered after the accident, at a cost of $45.05 each.

In an interview with a deputy UCLA fire marshal, Harran described what he saw before the paramedics arrived: Sheri “was, you know, she was in shock…she was shaking. I asked her what happened. She didn’t tell me much. She just said there was a fire, and she just kept asking, ‘Where are they, where are they, where are they?’…She wanted water on her arms, and she was holding her hands out like this, and the skin was separating. It was awful.”

Sangji was taken to the hospital. Shortly after 4 p.m. Pacific time, Naveen Sangji’s cellphone rang in Boston. Then a medical student at Harvard, she assumed her sister was calling to tell her about another law school acceptance letter. They had been coming regularly.?

It was a hospital social worker, using Sheri’s phone. Naveen caught a flight to Los Angeles early the next morning and went straight to the burn center to which her sister had been transffered. “Her arms were suspended from the ceiling to keep them in a certain position, all wrapped with bandages,” Naveen says. “The only part of her that I could see was her face.” Her sister would die less than three weeks later.?

“Willful violation”

?In the months to follow, Naveen pressed UCLA officials for details on the accident. She found the responses wanting. The university, she felt, was trying to make it appear that Sheri was an experienced chemist, and that the fire was her fault.

Cal/OSHA began one investigation shortly after the accident but before Sheri’s death; it resulted in four citations and a $31,875 fine against UCLA in May 2009. ?

On June 17, 2009, a month after the citations, Chancellor Block replyed to an email from Naveen. He recalled “the elegant and successful way” Sheri had performed the tert-Butyllithium experiment the previous October.? Block wrote that the “campus believes…that many corrective measures ordered by our inspectors were taken before the tragic accident, though they were not properly documented.” Cal/OSHA, he noted, “found no willful violations of regulations or laws by UCLA personnel. Neither [chemistry department chair Al] Courey nor Dr. Harran were in the lab the day of the tragedy and did not have the opportunity to remind Sheri to put on her lab coat.”

?In his interview with the deputy fire marshal, however, Harran—the lab’s principal investigator, or PI—admitted that his safety policies were less than rigid. Harran said he “never explicitly” told his senior employees, such as postdoctoral fellows, to make sure subordinates were wearing protective equipment.?

Sangji is not the only UCLA lab worker who suffered serious burns in recent years. In November 2007, a graduate chemistry student named Matthew Graf caught fire after spilling a bottle of alcohol near an open flame. He also wasn’t wearing a lab coat and sustained second-degree burns to his hands and torso. He spent a week in a burn center, and underwent surgery to repair his hands. Cal/OSHA didn’t learn about the accident until nearly two years after the fact and cited UCLA for failing to report it; the university is contesting the citation.?

And on December 22, 2008, one week before Sangji was burned, another graduate chemistry student, Jonah Chung, sustained burns and cuts when the equipment he was working on “detonated, causing glass, hot oil, and chemicals to strike his face and torso,” investigator Baudendistel wrote. Chung, who sustained burns and cuts “was not wearing a lab coat, gloves, nor appropriate eye protection…at the time of the incident.”?

UCLA Professor Patrick Harran in court CPIIn Naveen Sangji’s view, the fine in her sister’s case was sorely insufficient. So she was relieved and gratified when Baudendistel issued his 95-page report in December 2009, concluding that “the laboratory safety policies and practices utilized by UCLA prior to Victim Sangji’s death, were so defective as to render the University’s required Chemical Hygiene Plan and Injury and Illness Prevention Program essentially non-existent.” There had been “a systemic breakdown of overall laboratory safety practices at UCLA,” he wrote.?

UCLA Professor Patrick Harran in court CPIIn Naveen Sangji’s view, the fine in her sister’s case was sorely insufficient. So she was relieved and gratified when Baudendistel issued his 95-page report in December 2009, concluding that “the laboratory safety policies and practices utilized by UCLA prior to Victim Sangji’s death, were so defective as to render the University’s required Chemical Hygiene Plan and Injury and Illness Prevention Program essentially non-existent.” There had been “a systemic breakdown of overall laboratory safety practices at UCLA,” he wrote.?

“Dr. Harran,” Baudendistel concluded in the report, “permitted Victim Sangji to work in a manner that knowingly caused her to be exposed to a serious and foreseeable risk of serious injury or death.”

?Baudendistel referred the Harran case to criminal prosecutors, as is Cal/OSHA’s practice when it believes it has evidence of gross employer misconduct. ?While about a third of such referrals result in charges, Harran wasn’t a foreman on a trenching job or the owner of a roofing company. He was an award-winning chemistry professor with the backing of a powerful university.? He could be expected to fight back—vigorously.

Baudendistel recommended that Harran and UCLA be charged with involuntary manslaughter and felony labor code violations. But when the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office did file its felony complaint, this past December, the manslaughter charge was absent, leaving only willful violation of the state labor code.

Hard questions

?Chemists and safety consultants were stunned.? Across academia and private industry, the Sangji case had already set off debate; bloggers and journal editors had written about it. The filing of the complaint took the discussion to another level.? Uncomfortable questions followed: Were some principal investigators so obsessed with publishing papers, securing grants, and winning prizes that they’d lost sight of their responsibility to keep employees and students from being hurt??

“Each lab is like an island where the PI is king,” says Paul Bracher, a postdoctoral researcher in chemistry at Caltech who writes a blog called ChemBark. ?”He provides for the lab, brings in grants, decides how the money is spent. There are a lot of demands on their time, and the safety stuff a lot of times gets lost in the shuffle.

“I’ve never heard of anyone getting fired for being unsafe,” adds Bracher, whose trachea was pierced by flying glass in an undergraduate lab accident 12 years ago.

The US Chemical Safety Board has identified academic “fiefdoms” as being partly to blame for accidents like the one that killed Sangji. Its fall 2011 report concluded that at “academic research institutions, PIs may view laboratory inspections by an outside entity as infringing upon their academic freedom.” The board recommended that the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration revise its lab standard, which focuses on dangers from exposure to hazardous chemicals, to make clear that physical hazards also must be controlled. ?

UCLA, for its part, has created a Center for Laboratory Safety which, Chancellor Block said in his January statement, will “identify and institute best practices in safety, going beyond the minimum requirements of outside agencies so that we can hold our laboratories to even higher standards. We also dramatically increased the number of lab inspections, strengthened our policy on the required use of personal protective equipment and developed a hazard-assessment tool that labs must update annually or whenever conditions change.”

?The real-world impacts of these changes remain to be seen. “I think the university is trying,” says Rita Kern, a staff research associate in the UCLA Department of Medicine who sits on the health and safety committee of University Professional and Technical Employees, Communications Workers of America Local 9119 (UPTE), the union to which Sheri Sangji belonged. “Some things have changed, but it’s like turning a big boat in the middle of the ocean. It doesn’t turn very fast.”?

Indeed, after two inspections in the 14 months following Sangji’s death, Cal/OSHA cited UCLA for 16 lab safety violations. Five were classified as “serious” and one as “repeat serious.” The university paid a $36,690 fine.?

Ryan Marcheschi, a postdoctoral fellow in the UCLA chemical and biomolecular engineering department who works with flammable and explosive compounds, says the university has “tightened up” on safety since the Sangji accident, though much of this has come in the form of increased paperwork.? When he learned that the criminal complaint had been filed against Harran, “I thought it was extreme,” Marcheschi says. “But then I thought, maybe that’s what’s needed to make policies change.”?

UPTE’s health and safety director, Joan Lichterman, gives the district attorney’s settlement agreement with the UC regents a mixed rating. Lichterman likes the fact that PIs at UCLA no longer will be able to operate labs or supervise anyone without first completing safety training. But she doesn’t understand why the agreement ends after four years.

“Why only four years and not in perpetuity?” she asks.

The Center for Public Integrity is a non-profit, non-partisan independent investigative news outlet. For more of its stories go to www.iwatchnews.org. This story was done in collaboration with the Center for Investigative Reporting.