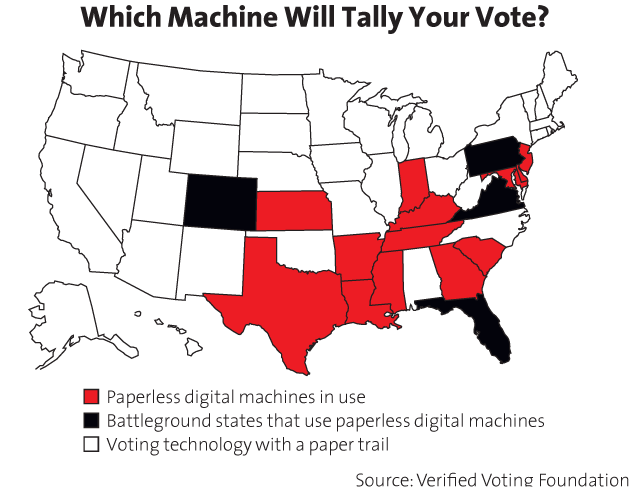

Update, November 6, 2012 (Election Day): At least one touch-screen voting machine in Pennsylvania was taken out of service because it was flipping votes for Obama to Romney.

This November, 25 percent of voters will cast ballots on digital voting machines that won’t leave a verifiable paper trail. Paperless voting machines are in use in four battleground states that account for 71 of the 270 electoral votes it takes to win.

What happens when paperless voting machines fail? Best case: Election results are delayed by a few hours or days. Worst case: The machine over- or undercounts votes, and there’s no way to verify the tally. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, such failures have caused the miscount or loss of anywhere from a few dozen to tens of thousands of votes in nine states. In 2006, the touch-screen iVotronic system in Florida’s Sarasota County recorded 13 percent of the 140,000 votes cast as blanks.

Can’t voting machines be hacked? There are no known cases. But investigations in California and Ohio, as well as independent studies, have shown that it’s not only possible but also would be hard to distinguish tampering from software or operational errors. A 2007 Princeton University study concluded, “Many computer scientists doubt that paperless [digital voting machines] can be made reliable and secure, and they expect that any failures of such systems would likely go undetected.”

Weren’t digital voting machines supposed to prevent these kinds of mistakes? Yes. The 2000 Florida recount catalyzed federal lawmakers to pass the Help America Vote Act in 2002. hava set aside some $4 billion to replace old punch card machines with digital ones. But there was little quality control as counties scrambled to deploy the new machines.

Who makes the machines? HAVA’s passage precipitated a “feeding frenzy” in the voting machine industry, according to Douglas Jones, a computer science professor and the co-author* of Broken Ballots, a new book on voting technology. In 2002, there were about a half-dozen major voting system vendors. Today there are two, Election Systems & Software and Dominion Voting Systems, which together control an estimated 70 to 90 percent of the market. (Diebold’s voting machine unit, once synonymous with doubts about digital voting, is now part of Dominion.)

So why aren’t voting machines more reliable—like ATMs? Simple, Jones explains: cost. If voting machines were built like medical and avionic equipment they’d cost around 10 times more than their current $4,000 price tag. “Truth is,” he says, “our democracy is at stake, but frankly we’re not prepared to pay that kind of money.”

Correction: The original version of this story stated that Douglas Jones is the author of Broken Ballots; he coauthored the book with Barbara Simons.