Illustrations by Steve Brodner

“There are two things that are important in politics. The first is money and I can’t remember what the second one is.“—Mark Hanna, 19th-century mining tycoon and GOP fundraiser

I. NIXONLAND

Bill Liedtke was racing against time. His deadline was a little more than a day away. He’d prepared everything—suitcase stuffed with cash, jet fueled up, pilot standing by. Everything but the Mexican money.

The date was April 5, 1972. Warm afternoon light bathed the windows at Pennzoil Company headquarters in downtown Houston. Liedtke, a former Texas wildcatter who’d risen to be Pennzoil’s president, and Roy Winchester, the firm’s PR man, waited anxiously for $100,000 due to be hand-delivered by a Mexican businessman named José Díaz de León. When it arrived, Liedtke (pronounced LIT-key) would stuff it into the suitcase with the rest of the cash and checks, bringing the total to $700,000. The Nixon campaign wanted the money before Friday, when a new law kicked in requiring that federal campaigns disclose their donors. Maurice Stans, finance chair of the Committee for the Re-Election of the President, or CREEP, had told fundraisers they needed to beat that deadline. Liedtke said he’d deliver.

Díaz de León finally arrived later that afternoon, emptying a large pouch containing $89,000 in checks and $11,000 in cash onto Liedtke’s desk. The donation was from Robert Allen, president of Gulf Resources and Chemical Company. Allen—fearing his shareholders would discover that he’d given six figures to Nixon—had funneled it through a Mexico City bank to Díaz de León, head of Gulf Resources’ Mexican subsidiary, who carried the loot over the border.

Winchester and another Pennzoil man rushed the suitcase to the Houston airport, where a company jet was waiting on the tarmac. The two men climbed aboard, bound for Washington. They touched down in DC hours later and sped directly to CREEP’s office at 1701 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, across the street from the White House. They arrived at 10 p.m.

It was the last gasp of a two-month fund-raising blitz during which CREEP raked in some $20 million before the new disclosure law took effect. A handful of wealthy donors accounted for nearly half of that haul; insurance tycoon W. Clement Stone alone gave $2.1 million, or $11.4 million in today’s dollars. Hugh Sloan, CREEP’s treasurer, later described an “avalanche” of cash pouring into the group’s coffers—all of it secret.

At least it was secret until some of that Mexican money ended up in the bank account of a one-time CIA operative named Bernard Barker, one of the five men whose bungled burglary at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex lit the fuse on the biggest political scandal in modern American history.

Over the next two years, prosecutors, congressional investigators, and journalists untangled a conspiracy involving a clandestine sabotage campaign against Democrats, hush-hush cash drops for CREEP surrogates in phone booths, and millions in illegal corporate contributions. As the slow drip of revelations continued, public outrage boiled over. Nixon’s approval rating sunk below 25 percent, worse than Lyndon Johnson’s during the darkest depths of the Vietnam War. Picketers marched on the White House demanding his impeachment. College campuses erupted in protest over the Watergate abuses.

Almost 40 years later, that outrage is back. Mass movements like the tea party and Occupy have channeled popular anger at a political system widely seen as backward and corrupt. In the age of the super-PAC, Americans commonly say there’s too much money in politics, that lobbyists have too much power, and that the system is stacked against the average citizen. “Our government,” as one Occupy DC protester put it, “has allowed policy, laws, and justice to be for sale to the highest bidder.”

For many political observers, it feels like a return to the pre-Watergate years. Rich bankrollers—W. Clement Stone then, Sheldon Adelson now—cut jaw-dropping checks backing their favorite candidates. Political operatives devise ways to hide tens of millions in campaign donations. And protesters have taken to the streets over what they see as a broken system. “We’re back to the Nixon era,” says Norman Ornstein of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, “the era of undisclosed money, of big cash amounts and huge interests that are small in number dominating American politics.” This is the story of how we got here.

Watergate aside, the issue of campaign finance historically has not resonated with Americans. Those few reporters who do concentrate on it—Mother Jones has made it a focus since our post-Watergate inception—struggle to breathe life into stories based on government documents and obscure regulations. But the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision—freeing corporations and unions to spend unlimited outside money on elections—jolted the public, prompting hundreds of protests and inspiring a nationwide grassroots campaign to, as the group Public Citizen puts it, “reclaim our democracy.”

Teddy’s Trust Issues Dark-money disaster: During the 1904 campaign, New York Life Insurance secretly gave $48,000 ($1.25 million today) to the Republicans.

Teddy’s Trust Issues Dark-money disaster: During the 1904 campaign, New York Life Insurance secretly gave $48,000 ($1.25 million today) to the Republicans.

Key figure: President Teddy Roosevelt, who ran as a trustbuster while soliciting corporate cash on the side. “He got down on his knees for us,” one tycoon recalled.

Backlash: Reformers howled. TR signed the 1907 Tillman Act, which banned companies from giving directly to candidates. We’ve been here before. The basic pattern emerging from the last century of campaign finance can be summarized as: scandal, then reform. The Tillman Act’s ban on corporate donations to candidates passed after Teddy Roosevelt was caught shaking down big New York City businesses. Watergate spurred the historic 1974 amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act. And the 1996 Democratic fundraising abuses paved the way for the passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, better known as McCain-Feingold. “Congress,” says Democratic election lawyer Joseph Sandler, “is always fighting the last war.” And whenever new reforms take effect, Washington’s brightest minds turn to finding clever new ways to circumvent them.

Political money, campaign finance watchers say, moves much like water, always looking for an opening to flow through—and political operatives are only too eager to muddy those waters with anonymous, untraceable cash. “It’s like holes in a dike: You block one hole, it’s going to find its way out another way,” says Democratic attorney Neil Reiff.

For decades, the campaign finance wars have pitted two ideological foes against each other: one side clamoring to dam the flow while the other seeks to open the floodgates. The self-styled good-government types believe that unregulated political money inherently corrupts. A healthy democracy, they say, needs robust regulation—clear disclosure, tough limits on campaign spending and donations, and publicly financed presidential and congressional elections. The dean of this movement is 73-year-old Fred Wertheimer, the former president of the advocacy outfit Common Cause, who now runs the reform group Democracy 21.

On the other side are conservatives and libertarians who consider laws regulating political money an assault on free markets and free speech. They want to deregulate campaign finance—knock down spending and giving limits and roll back disclosure laws. Their leaders include Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), conservative lawyer James Bopp Jr., and former FEC commissioner Brad Smith, who now chairs the Center for Competitive Politics, which fights campaign finance regulation.

In this ongoing battle, the upper hand shifts regularly. Wertheimer and his allies scored historic victories in the 1970s in the wake of Watergate and again in the early aughts. Yet more recently, the deregulation camp has won a series of court decisions—FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life, SpeechNow.org v. FEC, and, of course, Citizens United—that have toppled more campaign finance regulations in less time than ever before. Even the Tillman Act’s century-old corporate contribution ban is under siege by conservative interest groups.

Meanwhile, money is flooding the political system like never before. This has forced lawmakers, as many of them will forlornly admit, onto an endless fundraising hamster wheel in which they spend more and more time beating the bushes for campaign cash and less and less time actually legislating. In the 2012 election, experts project spending could top a staggering $11 billion—more than double the 2008 total.

What few people realize is how close Wertheimer and Congress came to blocking the deluge.

II. “That Bald-Headed Bastard”

The phone call that launched Fred Wertheimer’s four-decade crusade against corruption and corporate money in politics came, of all times, during a nap.

It was May 1971, and Wertheimer, then 32, was unemployed. After four years working for Rep. Silvio Conte (R-Mass.), Wertheimer had quit his job on the Hill and entered into what he now calls “semiretirement.” He slept late, browsed the newspapers, took long walks around Washington, and napped each afternoon. Having bills to pay, his wife, Linda, took a job at a fledgling news organization called National Public Radio. (She went on to a long career at NPR as a political correspondent and host of All Things Considered.) Wertheimer himself had applied for a handful of jobs, but he hadn’t heard back.

* Includes primaries when known. Sources: Center for Responsive Politics; George Thayer, Who Shakes the Money Tree?Then, one afternoon, he awoke to a phone call. Wertheimer, groggy, reached for the receiver. It was the good-government group Common Cause, where he had applied for a lobbying position. They wound up hiring him to focus on two issues: ending US involvement in the Vietnam War and reforming the nation’s weak campaign finance laws.

* Includes primaries when known. Sources: Center for Responsive Politics; George Thayer, Who Shakes the Money Tree?Then, one afternoon, he awoke to a phone call. Wertheimer, groggy, reached for the receiver. It was the good-government group Common Cause, where he had applied for a lobbying position. They wound up hiring him to focus on two issues: ending US involvement in the Vietnam War and reforming the nation’s weak campaign finance laws.

In a recent interview at his Dupont Circle office, the walls adorned with Mark Rothko prints, framed news clips (“Ethics Watchdog Fred Wertheimer: When He Barks, Congress Listens”), and photos inscribed by the politicians he’s worked with (Barack Obama: “Keep fighting the good fight”), Wertheimer, a Brooklyn native with a crown of silver hair, recalled the warning he received from Common Cause founder John Gardner: “Reform is not for the short-winded.” Even so, Wertheimer quips, “He never told me it was 41 years and counting.”

Luckily for Wertheimer, he had an early taste of victory to keep him going. Watergate and the abuses of the 1972 presidential campaign had left the public agitating for reform, and both Democrats and Republicans in Congress scrambled to introduce new legislation overhauling the nation’s campaign finance laws. By 1974, there were five different campaign finance bills bouncing around in the Senate, four with GOP cosponsors. The point man on one of them was none other than the Senate minority leader, Pennsylvania Republican Hugh Scott.

For much of 1974, Wertheimer shuttled around the ornate Russell Senate Office Building, his loafers clicking on the polished marble floors. He was the top lobbyist in the reform push, the broker between lawmakers working on various versions of the historic campaign finance legislation. The five bills were soon boiled down into one that included limits on campaign spending and donations, the creation of a new elections watchdog, and public financing programs for presidential and Senate races. The legislation also left open the possibility of public financing for House campaigns. It was as close to the Common Cause ideal as Wertheimer could’ve hoped for. The House and Senate passed their own versions of the bill with bipartisan support, then headed into conference to iron out the differences.

Wertheimer’s enemies seethed. One was Rep. Wayne Hays (D-Ohio), a sour bull of a politician who chaired the House Administration Committee and loathed campaign finance reform. Like many old-school pols, Hays saw the reforms as a threat to his seat. (Hays would later resign after it was revealed he’d paid his mistress to work in his office.) He’d fought Wertheimer—the “skunk”—every step of the way, stalling or killing campaign finance legislation. One of the 1974 conferees, Hays once spotted Wertheimer lingering outside the meeting room, seemingly twisting lawmakers’ arms. Wertheimer says another member of Congress relayed Hays’ snarling, behind-closed-doors reaction: “What’s that bald-headed bastard doing here?”

Watergate Dark-money disaster: President Richard Nixon’s 1972 reelection campaign raked in $20 million in secret donations; some went to fund the Watergate break-in. Nixon told his chief of staff to inform donors, “Anybody who wants to be an ambassador must at least give $250,000.”

Watergate Dark-money disaster: President Richard Nixon’s 1972 reelection campaign raked in $20 million in secret donations; some went to fund the Watergate break-in. Nixon told his chief of staff to inform donors, “Anybody who wants to be an ambassador must at least give $250,000.”

Key figure: Herbert Kalmbach, Nixon’s personal attorney and the deputy finance chair for the Committee for the Re-Election of the President, who destroyed evidence of the hushed donations. He was fined $10,000 and served six months in prison.

Backlash: Congress imposed new limits on campaign gifts and set up the Federal Election Commission.Hays and the other conferees ultimately denied Wertheimer his grand slam of reforms by scrapping congressional public financing. Still, the limits on campaign spending and donations and the creation of the Federal Election Commission made for a stunning victory. In the final vote, 75 percent of House Republicans backed reform, as did 41 percent of Senate Republicans. On October 15, 1974, President Gerald Ford signed into law the amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), the bedrock of modern campaign finance law.

The amendments took effect on January 1, 1975. The very next day, Sen. James Buckley (R-N.Y.)—older brother of conservative icon William F. Buckley—sued the secretary of the Senate, Francis Valeo, in an all-out attack on the constitutionality of FECA. Buckley v.Valeo reached the Supreme Court in September 1975, and four months later the high court handed down a bittersweet ruling for Wertheimer. In a complex and at times impenetrable opinion—one thought to have been written by as many as five justices—the court upheld the law’s contribution limits, presidential public financing program, and disclosure provisions. But it struck down the limits on spending, including so-called independent expenditures—money spent by individuals or outside groups “totally independent” of campaigns. Buckley deemed political money a form of speech and sought to balance two interests: the First Amendment’s free speech protections and what the justices termed “corruption and the appearance of corruption.” Money given straight to candidates could corrupt, the court argued, but independent expenditures did not and thus couldn’t be limited.

Buckley not only wiped out chunks of the 1974 law—it has shaped most major campaign finance court decisions ever since. The Roberts court drew heavily on Buckley in its Citizens United decision, which opened the door to unlimited third-party spending and radically reshaped the political playing field. “Buckley,” says Michael Toner, a former chairman of the FEC and onetime chief counsel to the Republican National Committee, “is a seed that has sprouted a thousand blossoms.”

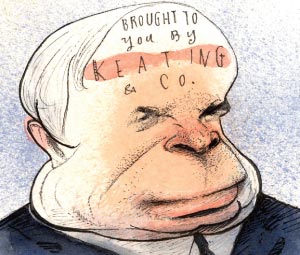

The Keating Five Dark-money disaster: After receiving a combined $1.3 million in donations, five Democratic and Republican senators met with banking regulators on behalf of Charles Keating’s failing S&L.

The Keating Five Dark-money disaster: After receiving a combined $1.3 million in donations, five Democratic and Republican senators met with banking regulators on behalf of Charles Keating’s failing S&L.

Key figure: Mildly rebuked by the Senate Ethics Committee in 1991, a chastened Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) said, “I’m sure that my political obituary will always have something about the Keating Five in it.”

Backlash: In a roundabout way, the 2002 McCain-Feingold Act.

III. PAC ATTACK

“It was reported I once called George McGovern a grossly overeducated SOB.” Pause. “I’ve never called him educated.” Laughter filled the Riverview Room at the Watergate Hotel. It was May 18, 1983, and the 200 or so guests, among them congressmen and senators and luminaries of the Reagan Revolution, doubled over their $110-a-plate dinners and glasses of wine. At a roast in his honor, John T. (“Terry”) Dolan had stolen the show.

The guests had every reason to celebrate Dolan. A Reagan disciple and brash political operative, Dolan was the founder of the National Conservative Political Action Committee, known as NCPAC (pronounced “nick pack”). Freed by the Buckley decision, which shot down fundraising and spending limits on independent groups, Dolan forged NCPAC into a formidable political machine. He raised and spent as much money as he could, and he helped pioneer the dark art of the attack ad. One ad bashing McGovern, the South Dakota senator, showed a basketball player dribbling a ball as an announcer said: “Globetrotter is a great name for a basketball team, but it’s a terrible name for a senator. While the energy crisis was brewing, George McGovern was touring Cuba with Fidel Castro.”

NCPAC famously spent $1.2 million in the 1980 election relentlessly attacking six Democratic lions of the Senate; four of them—McGovern, Birch Bayh of Indiana, Frank Church of Idaho, and John Culver of Iowa—would lose. On just one day during the ’80 campaign, NCPAC ran 150 anti-Church ads on Idaho radio stations. NCPAC also spent $2 million to help Reagan beat President Jimmy Carter. In the 1984 presidential election, it dropped another $2 million hammering Walter Mondale. The country had never seen anything like Dolan’s outside attack machine—and he knew it. “We’re on the cutting edge of politics,” he told the Washington Post in 1980.

Dolan made no bones about his brass-knuckles style. “A group like ours,” he once said, “could lie through its teeth, and the candidate it helps stays clean.” Democrats branded Dolan a lying “extremist,” while patrician Republicans sneered at his smashmouth tactics. Yet when they weren’t bashing Dolan, his enemies scrambled to catch up. Strategist Peter Fenn urged fellow Democrats to “get down in the gutter with NCPAC” if they wanted to win.

Slim and mustachioed, Dolan loved telling biting jokes and encouraged a loose atmosphere around the NCPAC office, where water gun fights were common and hamsters roamed the halls. Dolan also groomed future Republican operatives, including message guru Frank Luntz, conservative media watchdog L. Brent Bozell III, political strategist Mike Murphy, and PR man and political historian Craig Shirley.

Thanks in part to Dolan’s audacious brand of politics, Reagan was twice elected president. Dolan, however, didn’t live to see the end of the Reagan era. A closeted gay man, he died from AIDS-related complications in 1986, at the age of 36. His friends, who never spoke of his illness, hailed him as a pillar of the New Right movement and a canny tactician who changed the way politics was played—if not always for the better.

NCPAC, which faded away in the years after Dolan’s death, illustrated a larger trend in post-Buckley politics: the rise of the political action committee. At the end of 1974, there were 600 registered PACs; nine years later, there were 3,500. PACs spent $23 million on congressional races in 1976; by 1982, it was $80 million.

NCPAC, which faded away in the years after Dolan’s death, illustrated a larger trend in post-Buckley politics: the rise of the political action committee. At the end of 1974, there were 600 registered PACs; nine years later, there were 3,500. PACs spent $23 million on congressional races in 1976; by 1982, it was $80 million.

PACs came in all varieties: independent committees like NCPAC, trade association PACs, party PACs, and more. There were PACs representing whole industries, like the mighty Business Industry Political Action Committee (BIPAC), formed by the National Association of Manufacturers, which grew so large and cash-flush that in the 1980s it rivaled the parties as the true power broker in Washington.

The presidential candidates started their own committees. Reagan’s Citizens for the Republic PAC, for instance, acted as a campaign-in-waiting between his ’76 and ’80 presidential bids. The group held on to leftover donations and safeguarded valuable mailing lists while quietly laying the groundwork for his successful 1980 election campaign.

The rise of business and corporate PACs—and also innovations like direct mail—helped the Republican Party dominate the arms race of the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1980 campaign, for instance, the GOP spent $5 million in support of Senate candidates, compared to the Democratic Party’s $590,000. Two years later, the Republican National Senatorial Committee doled out $9 million to candidates, while the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee gave just $2.3 million.

Yet the explosion of new PACs soon ended, and though they remain a fixture of electoral politics to this day, their luster faded. As the ’80s wore on, a loophole opened by the FEC gave rise to soft money—unregulated, undisclosed, unlimited money given to parties (as opposed to candidates) by unions, corporations, and wealthy individuals. At first, the FEC let the parties raise and spend soft money solely for “party-building activities”: building a new office, say, or a TV studio. But election lawyers and savvy strategists soon widened the loophole.

Politicos remember 1988 as the first election when soft money figured in a big way. Joseph Sandler, then a lawyer at the Democratic National Committee (and later its general counsel), recalls soft money from unions and corporations pouring into the party’s coffers after Michael Dukakis seized the nomination. “We thought, ‘What do we do with it?'” Sandler says. “So we invented new uses for soft money for general party stuff to get out the vote.” That included phone banks, surveys, direct mail, and other administrative costs.

The parties raised $45 million in soft money in 1988; in 1992, it was $86 million. By then Wertheimer, the reformers, and newspaper editorial boards around the country were decrying what they saw as a perversion of the campaign finance laws. In May 1993, a newly elected President Bill Clinton paid lip service to banning soft money, but a bill to do just that died in conference, after passing both the House and Senate.

The bill’s demise would prove a blessing and a curse for Clinton. Soft money would power his reelection campaign two years later—yet it would also trigger the biggest campaign finance scandal since Watergate.

IV. “The White House Is Like a Subway”

On September 7, 1995, Bill Clinton joined his top aides and advisers for a strategy session in the White House’s second-floor Treaty Room. It was here, on a muggy August day in 1898, that William McKinley had presided over the signing of a treaty that had ended hostilities in the Spanish-American War. Now, Clinton and his lieutenants faced a war of a different kind: winning reelection in the face of vicious GOP attacks and a hobbled US economy.

The loudest voice in the room that day belonged to Dick Morris, the charismatic and controversial political strategist. “It’s complicated” was the best way to describe the relationship between Clinton and Morris. The president had hired, fired, and rehired Morris throughout his two-decade ascent from obscure Arkansas official to governor to leader of the free world. Shortly after the Democrats’ midterm hammering in November 1994, Clinton turned to Morris once again to chart a course to victory in the 1996 election.

Morris, as usual, had a plan.

The party, he said, needed to saturate the airwaves with TV ads starting now, 14 months before Election Day, in Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, and other swing states. Advertising early and often, getting out in front of the GOP, was key to winning the ’95 budget fight and the ’96 election. “If we win now, we’ll win later,” Morris said at the meeting. “If we lose now, we’ll be dead no matter what we do.”

The Democrats’ weapon of choice were so-called issue ads slamming the GOP and its leader, House Speaker Newt Gingrich, for a budget that cut funding for Medicare, Medicaid, and Head Start. The ads would also tout Clinton’s pledge to cut taxes on the middle class, beef up environmental protections, and balance the budget without axing popular programs. In reality, the ads were campaign spots. All that was missing was the “Vote for Bill Clinton” tagline. Why the feint? As long as Democrats claimed they were running issue ads, they could fund them with soft money.

Clinton signed off.

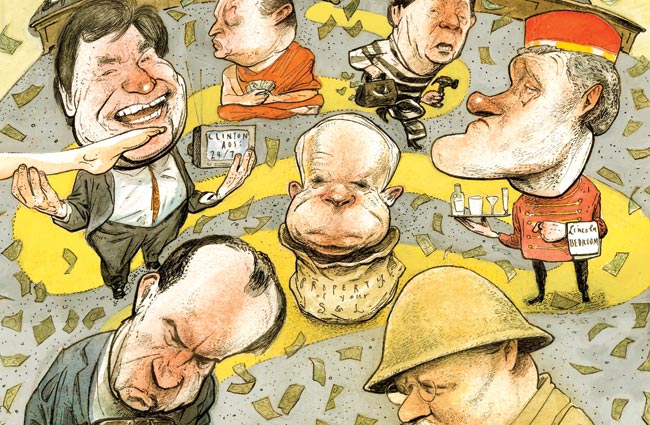

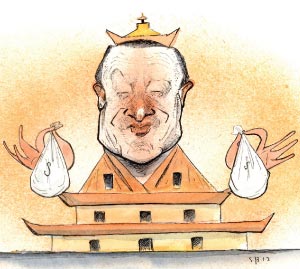

The Clinton Years Dark-money disaster: In 1996, a California Buddhist temple illegally funneled $65,000 to the Democrats at an event attended by Vice President Al Gore. The Dems eventually returned nearly $3 million in illegal donations, some from foreign donors. Meanwhile, big donors were offered Lincoln Bedroom sleepovers, coffees, golf outings, or morning jogs with President Bill Clinton.

The Clinton Years Dark-money disaster: In 1996, a California Buddhist temple illegally funneled $65,000 to the Democrats at an event attended by Vice President Al Gore. The Dems eventually returned nearly $3 million in illegal donations, some from foreign donors. Meanwhile, big donors were offered Lincoln Bedroom sleepovers, coffees, golf outings, or morning jogs with President Bill Clinton.

Key figure: Fundraisers Charlie Trie, John Huang, Johnny Chung, Maria Hsia, and James Riady, an Indonesian businessman who was fined $8.6 million.

Backlash: Spurred passage of McCain-Feingold in 2002, which banned unregulated soft money to parties.There was just one problem: The DNC was broke. Democrats would need to raise tens of millions of dollars, fast; thankfully, they had the ultimate rainmaker in Clinton. The president hated asking for money, a former aide recalls, yet no one schmoozed a room full of rich people like Clinton. “He was a master at talking to them about what he was doing and where he wanted the country to go—and by the way, we need some money to get there,” the aide says.

In the months that followed, the White House and DNC sent a clear message to donors: Bring your checkbooks; we’re open for business. Clinton attended more than 230 fundraising events in the 10 months before the election, sometimes five or six a week. “Every minute of my time is spent at these fundraisers,” the president griped. Donors, meanwhile, knew access was just a six-figure check away. “The White House is like a subway,” said one contributor. “You have to put in coins to open the gates.”

And how those coins added up. The DNC raised more than $122 million in soft money during the ’96 cycle. The RNC did even better, raking in $141 million. Together, the two parties unleashed $120 million in soft money on faux issue ads.

Yet Morris’ strategy put the Democrats’ soft money to far more devastating use. One issue spot, crafted by ad man Marius Penczner, depicted a patient’s beeping EKG monitor slowly flatlining as a narrator read the GOP’s proposed health care cuts. In another, a little girl played in her crib while the narrator rattled off GOP-backed education cuts. And the ads ran relentlessly: By Election Day of November 1996, the average TV viewer in targeted states saw one Democratic issue ad every three days.

The barrage was later credited with opening a wide lead for Clinton nearly a year before the election. Although the RNC caught on to Morris’ strategy and mimicked it, GOP candidate Bob Dole never closed the gap. Looking back on his ad strategy and the ’96 election, Morris later wrote, “There has never been anything even remotely like it in the history of presidential elections.”

Then, after Election Day, the details of the Democrats’ fundraising scheme exploded into a full-blown scandal. Sen. Fred Thompson (R-Tenn.), who had worked on the Senate’s Watergate investigation two decades earlier, launched a probe that eventually forced the Clinton administration and the DNC to admit to plying donors with coffee klatches with the president, sleepovers in the White House’s Lincoln Bedroom, rides on Air Force One, and other exclusive perks. It emerged that John Huang, a major Democratic fundraiser and the DNC’s vice chairman of finance, had laundered nearly a million dollars in illegal foreign contributions to the DNC from an Indonesian conglomerate and a Korean electronics company, among other sources. Democrats also accepted $65,000 in illegal donations at a now-infamous luncheon at a Los Angeles-area Buddhist temple. The DNC would later return about $3 million.

For Fred Wertheimer and the reformers, Clinton’s soft money operation marked a return to the dark-money days of Watergate. “Though still on the books, campaign finance laws have been replaced by the law of the jungle,” Wertheimer fumed at the time.

The pendulum was swinging back to reform.

V. “LEGISLATIVE SLEDGEHAMMER”

A few days after Republicans recaptured the Senate in the 1994 midterm elections, Russ Feingold was driving through Wisconsin in his used, blue, wood-paneled Buick Roadmaster station wagon. Before the “tsunami of ’94,” Feingold had ranked last in seniority in his party, but at least Democrats controlled the Senate. Now he had even less clout on the Hill. Somewhere outside Madison the wagon’s hulking car phone rang. The ensuing conversation changed Feingold’s life.

On the line was Arizona’s John McCain. The veteran Republican senator praised Feingold’s work, his independence, and his determination, and suggested that the two men team up on legislation. Feingold—knowing that McCain had remade himself as a reformer after getting ensnared in the 1989 Keating Five banking scandal—suggested campaign finance.

Thus began one of the unlikeliest yet most influential partnerships in the history of money in politics.

In the decade before, reformers in Congress had introduced new campaign finance laws every session. Each time the legislation perished on the floor or met the veto of the president. McCain and Feingold would face the same pattern until, in the wake of the ’96 scandal, a window for reform opened once again.

A pivotal moment came in 1997. The two senators had watched in horror at the explosion of soft money in the previous year’s election. At a meeting in Feingold’s Senate office, McCain pressed to scrap their existing bill and replace it with a straightforward soft money ban, which he believed held the best hope of passing. Fein-gold wouldn’t hear of it, since doing so would entail jettisoning measures dear to his heart, including one that would abolish PAC contributions. McCain left Feingold’s office furious. McCain-Feingold almost died right then and there.

The next day, the two met in the Republican cloakroom just off the Senate floor. Feingold could see that McCain was still unsettled by their argument. “Russ, I was up all night,” he said. “I was so upset.”

“I think you’re right, John,” Feingold told him. “We gotta get this. We gotta pass the soft money ban.” The men hugged.

Following the ’96 election, Wertheimer had predicted that Congress had only a 90-day window to pass a soft money ban before the public’s anger dissipated. In fact, it took more than five years, by which point McCain had begun calling himself Sen. Quixote.

McCain and Feingold had plenty of help. Wertheimer, who’d moved on to Democracy 21, lobbied relentlessly. More crucial was a decadelong influx of money from the nation’s biggest charities and foundations that started in the mid-’90s—upward of $140 million—to fund reform groups and underwrite new campaign finance research. “The idea was to create an impression that a mass movement was afoot, that everywhere [politicians] looked—in academic institutions, in the business community, in religious groups, in ethnic groups, everywhere—people were talking about reform,” Sean Treglia, who led Pew Charitable Trusts’ campaign finance program, later said.

But it was serendipity as much as money or momentum that nudged McCain-Feingold over the edge. On May 24, 2001, Jim Jeffords, Vermont’s junior senator and a lifelong Republican, defected from the GOP and declared himself an independent. For the first time in history, control of the Senate changed hands without an election. Sen. Trent Lott (R-Miss.), a staunch opponent of McCain-Feingold, relinquished the title of majority leader to Sen. Tom Daschle (D-S.D.). “Jeffords flips, Daschle comes into control, and we can see the finish line,” recalls Bob Schiff, Feingold’s top lieutenant on campaign finance.

But it was serendipity as much as money or momentum that nudged McCain-Feingold over the edge. On May 24, 2001, Jim Jeffords, Vermont’s junior senator and a lifelong Republican, defected from the GOP and declared himself an independent. For the first time in history, control of the Senate changed hands without an election. Sen. Trent Lott (R-Miss.), a staunch opponent of McCain-Feingold, relinquished the title of majority leader to Sen. Tom Daschle (D-S.D.). “Jeffords flips, Daschle comes into control, and we can see the finish line,” recalls Bob Schiff, Feingold’s top lieutenant on campaign finance.

The rest of 2001 saw McCain, Feingold, and their fellow reformers fight off an onslaught of amendments aimed at kneecapping their bill. Finally, in the winter of 2002, after the House passed its version of the legislation by a 51-vote margin, the Senate easily green-lighted the bill. McCain-Feingold headed to the desk of President George W. Bush.

At 7 a.m. on March 27, 2002, the duo’s seven-year campaign ended as it began: with a phone call. A Bush White House aide phoned McCain at his home in Arizona to inform him that the president had signed McCain-Feingold into law that morning. There was no signing ceremony, no Rose Garden press conference. A commemorative pen would be delivered shortly to McCain’s Capitol Hill office.

That same morning, a few blocks east of the White House, a staffer from a law firm representing the National Rifle Association stood shivering on the front steps of the US District Court and holding a sheaf of papers. The staffer’s instructions were to file the NRA’s lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of McCain-Feingold the minute the courthouse opened. With the ink still wet on the two senators’ crowning achievement, the assault began.

By beating the other challengers to the court that morning, the NRA earned the naming rights to what promised to be a blockbuster case destined for the Supreme Court. National Rifle Association v. FEC, the legal textbooks would read.

Then Sen. Mitch McConnell, one of Washington’s fiercest foes of campaign finance laws, stepped into the fray.

A stiff, jowly conservative born in Tuscumbia, Alabama, McConnell was known mostly for two things: his encyclopedic knowledge and mastery of congressional procedure, and his First Amendment zealotry. McConnell slammed McCain-Feingold as a “legislative sledgehammer” that would smash the First Amendment’s free speech protections to bits. The law, he argued, “constitutes the most threatening frontal assault on core First Amendment values in a generation.”

On the day Bush signed McCain-Feingold, McConnell filed a suit of his own challenging the new law’s constitutionality. He’d already assembled a murderer’s row of lawyers to argue his case, among them then-Stanford Law dean Kathleen Sullivan, First Amendment guru Floyd Abrams, and James Bopp Jr., a shrewd attorney who had built a career out of demolishing campaign finance laws. Though McConnell had filed his suit after the NRA, he wanted his name on the case. And so in a rare move, McConnell brokered a backroom deal with the NRA to swap the group’s name for his. The case would be called McConnell v. FEC. “He wanted it; he was the leader,” recalls Cleta Mitchell, an attorney for the NRA on the McConnell case. “The NRA knew it would be foolish to make a mortal enemy of a powerful senator over something like naming rights.”

It wasn’t the first time McConnell had set out to gut the nation’s campaign finance laws. Long before he challenged McCain-Feingold, McConnell had trained his sights on the FEC. If he couldn’t get rid of campaign finance regulations altogether, he knew defanging the nation’s elections watchdog would weaken enforcement.

In 1998, after the FEC launched probes of Newt Gingrich’s political slush fund, GOPAC, and Pat Robertson’s Christian Coalition, McConnell took aim at the commission’s top lawyer, a fast-talking Queens native named Larry Noble. Noble was an FEC lifer who’d joined the commission soon after it opened in 1975. No fan of Noble or his aggressive style, McConnell wrote an amendment essentially firing him and slipped it into a $27 billion funding bill for the Treasury Department, Postal Service, and other federal agencies. Democrats howled in protest; the New York Times published four editorials in Noble’s defense, calling McConnell’s amendment an “attempted lynching.” (McConnell denied specifically targeting Noble.)

Republicans on the House side kept up the fight McConnell had started. On the evening of October 1, 1998, their attack on Noble burst into public view on the House floor when Democrats vowed to block the Treasury and postal bill until Noble was safe. Millions in funding for anti-cybercrime efforts, the DARE anti-drug campaign, and an entire fleet of Black Hawk helicopters were in limbo.

Noble watched wide-eyed as this drama played out on his TV back home in Maryland. “Wow, Dad,” Noble’s 11-year-old son marveled. “I can’t believe you’re worth 16 Black Hawk helicopters.”

Throughout the 2000s, McConnell also reshaped the six-member FEC by exerting control over the nominating process. Former commissioner Brad Smith, whom McConnell tapped for the post, recalls, “He essentially said, ‘We need to put Republicans on the FEC who favor our point of view on regulation.'” McConnell leveraged his Senate clout to install ideologues hostile to campaign finance law. One of them, Donald McGahn, later told a group of students at the University of Virginia Law School that he simply would not enforce the laws he’d been hired to uphold. “I plead guilty as charged,” he said.

Eventually, McConnell’s FEC strategy would pay off. The number of 3-to-3 deadlocks on enforcement actions averaged 1 percent between 2003 and 2007; it shot up to 16 percent in 2009 and was 11 percent in 2010. For much of 2008, the FEC was so tangled that the commission lacked the minimum four-person quorum to even function. Political outfits have capitalized on the commission’s hobbled state. The percentage of groups disclosing their donors dropped by more than 43 percent between 2004 and 2010.

But while McConnell succeeded in his behind-the-scenes maneuver, the fight he’d put his name on didn’t go so well. Conventional wisdom suggested the Supreme Court would side with McConnell in the challenge to McCain-Feingold. Instead, the high court’s 5-to-4 decision, handed down on December 10, 2003, upheld nearly the entire law, humbling McConnell and his legal team. McConnell v. FEC is now remembered as a high-water mark for the reform community.

VI. In the Hands of the Court

James Bopp Jr. read the 300-page McConnell decision in disbelief back at his law office in Terre Haute, an old southwest Indiana mining town of 70,000 on the banks of the Wabash River.

An unassuming Hoosier with neatly parted silver hair and a cool, measured demeanor, Bopp was a central figure in the conservative movement to deregulate campaign finance that, in the 2000s, took the fight to Wertheimer and the reformers, brought the Citizens United case, and helped usher in super-PACs. Before, conservatives and libertarians had struggled to organize themselves on money in politics. “You had the ACLU, a few cranky libertarian sorts, a stray report from the Cato Institute, and some lackeys in the fight trying to preserve their own interests,” Smith says. “That began to change after McConnell.” At the heart of that pushback was Bopp.

An unassuming Hoosier with neatly parted silver hair and a cool, measured demeanor, Bopp was a central figure in the conservative movement to deregulate campaign finance that, in the 2000s, took the fight to Wertheimer and the reformers, brought the Citizens United case, and helped usher in super-PACs. Before, conservatives and libertarians had struggled to organize themselves on money in politics. “You had the ACLU, a few cranky libertarian sorts, a stray report from the Cato Institute, and some lackeys in the fight trying to preserve their own interests,” Smith says. “That began to change after McConnell.” At the heart of that pushback was Bopp.

Bopp’s crusade dates back to his early childhood. Born into a conservative Midwestern family, the conversation at home often revolved around politics and government, he recalls, and young Jim devoured books on conservative and libertarian philosophy. At Boy Scout camp in rural Indiana, Bopp remembers reading the works of Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, a founding father of the libertarian movement, by flashlight in his tent. “I never had a heart,” Bopp jokes today. “I only had a brain.”

Bopp attended Indiana University (he still has basketball season tickets) and law school at the University of Florida, and then, in 1978, he got hired as general counsel for the group National Right to Life. The turning point in his legal career came in 1993. Ten days before a statewide election, a Democratic judge blocked two Virginia anti-abortion groups from distributing voter guides on the basis that the pamphlets violated electioneering laws. Outraged at what he saw as a body block on the organizations’ free speech rights, Bopp got the judge to lift the injunction the day before the election. But the damage to their campaign had been done. At the next meeting of National Right to Life’s state chapters, Bopp urged the groups’ leaders to go on the offensive. “Sue ahead of time,” he advised them. “Get rid of these laws so [you’re] not victimized like that.”

Bopp has been in attack mode ever since. With anti-abortion groups as ready-made standard bearers, he has challenged and defeated more than 150 campaign finance laws. In recent years, he’s represented same-sex marriage opponents in California and Washington state in a broader effort to topple donor disclosure laws. (See Mother Jones‘ May/June 2011 issue for an in-depth profile of Bopp.)

Paul S. Ryan, senior counsel at the pro-reform Campaign Legal Center, says Bopp’s use of the culture wars to attack political money regulations is central to understanding his influence and success. “Bopp recognizes something that few on the left recognize: that campaign finance law underlies all other substantive law,” Ryan says. “If you can deregulate money in politics, you can buy the policy outcomes you prefer.”

Hammer Time Dark-money disaster: GOP Majority Leader Tom “The Hammer” DeLay snuck around a ban on corporate donations by funneling them through the Republican National Committee back to Texas Republicans.

Hammer Time Dark-money disaster: GOP Majority Leader Tom “The Hammer” DeLay snuck around a ban on corporate donations by funneling them through the Republican National Committee back to Texas Republicans.

Key figure: DeLay, who was convicted of money laundering and sentenced to three years in prison, all while condemning “the criminalization of politics.” He’s currently out on bail while appealing.

Backlash: DeLay lasted just three weeks on Dancing With the Stars.In 1997, Bopp created the James Madison Center for Free Speech, which once counted McConnell as an honorary chairman, to give fellow conservatives a platform in the political money trenches. Sometimes that meant battling members of their own party—including Ken Mehlman, who as RNC chairman called for a ban on outside 527 groups during the 2004 election. Elected as an RNC delegate in 2005, Bopp pressed the party to embrace a deregulatory position on campaign finance. Freedom to raise and spend campaign money without restrictions, he says, should be “a central part of our philosophy.”

Bopp brushes aside questions about the wisdom of wanting more cash sloshing around politics when most of the public wants less of it. He doesn’t buy the argument that more campaign giving erodes public trust in government—and if it did, he says, that would be a good thing: “People should rely less on government anyway. The less government there is, the better off we all are.”

By the mid-2000s, the campaign finance deregulation movement had fully blossomed. Brad Smith had left the FEC and formed the Center for Competitive Politics, a rival to Common Cause and Wertheimer’s campaign finance reform group Democracy 21. The Institute for Justice, a libertarian law firm, waded into campaign finance legal fights in hopes of knocking down regulations. And Bopp was plowing ahead with his right-to-life cases and other election-related lawsuits. “All of this created a new esprit de corps,” Smith says. “For the first time, it was okay to walk around Washington and say it’s respectable to oppose campaign finance reform.”

Bopp and his allies also saw their fortunes radically improve with the arrival of John Roberts and Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court during George W. Bush’s second term. Reformers and legal experts argue, in fact, that the switch from Sandra Day O’Connor to Alito marked the single most crucial moment in the past decade of the money wars. In an instant, the key fifth vote in McConnell was replaced by Alito, a reliable conservative with a libertarian streak.

The effect was near-instantaneous. In 2007, Bopp argued in FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life that McCain-Feingold’s ban on running issue ads 30 days before a primary and 60 days before an election was unconstitutional. The court had upheld this very provision four years earlier; the Roberts court killed it. Then, in January 2010, the court ruled 5-to-4 in Citizens United—another case brought by Bopp (though he didn’t argue it before the court)—that corporations and labor unions are entitled to the same free speech protections as people and so can spend directly from their general treasuries on unlimited independent expenditures. Citizens United had arrived at the court as a minor case with few implications for campaign finance. But Roberts and his fellow conservative justices used the case to issue a ground-shaking decision that demolished decades of precedent. (Later that year, a DC appeals court relied on Citizens United in a case called SpeechNow.org v. FEC, argued by Brad Smith’s Center for Competitive Politics, which ushered in super-PACs.)

Citizens United Dark-money disaster: In a January 2010 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that limits on outside political spending by corporations and unions violate the First Amendment. Paved the way for the creation of super-PACS.

Citizens United Dark-money disaster: In a January 2010 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that limits on outside political spending by corporations and unions violate the First Amendment. Paved the way for the creation of super-PACS.

Key figure: Chief Justice John Roberts; justices Samuel Alito, Anthony Kennedy, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas; and legal mastermind James Bopp.

Backlash: Increasing calls for a constitutional amendment to undo Citizens United. (See our DIY guide to undoing Citizens United.)Wertheimer called Citizens United “a disaster for the American people” and “the most radical and destructive campaign finance decision in Supreme Court history.” The American Enterprise Institute’s Norman Ornstein says the decision was as misguided as the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford ruling denying slaves the right to citizenship. “The Roberts court is going to go down in history in the same way [Chief Justice] Roger Taney and his court went down in history with Dred Scott,” Ornstein says. In his 2010 State of the Union, President Obama himself lambasted the high court for having “reversed a century of law that I believe will open the floodgates for special interests.”

The Roberts court’s hostility to limiting money in politics has forced the reformers to overhaul their strategy. The Campaign Legal Center’s Paul S. Ryan says groups like his now struggle to fund legal defenses of what’s left of campaign finance law. Donors see any legal strategy dead-ending at the Supreme Court—and Ryan agrees. “With the Supreme Court the way it is,” he says, “why bother?”

The reformers have instead taken the fight to Congress with legislation bolstering disclosure in campaign giving and political ads, but they have little to show for it. The 2010 DISCLOSE Act died in the Senate after Republicans, led by McConnell, filibustered the bill. A slimmed-down version of the legislation, introduced in March, faces similarly long odds. It’s a tough time, Wertheimer admits, to be a reformer in Washington.

Stymied in the courts and in Congress, the fight against super-PACs and dark money in politics is now being waged in the streets. Buoyed by the Occupy movement, activists nationwide are knocking on doors, lobbying state lawmakers, and rallying at courthouses in an effort to ensure campaign finance is not a back-burner issue.

On December 15, in 83 towns and cities, from Burlington, Vermont, to Anchorage, Alaska, people gathered in living rooms and kitchens to discuss Citizens United and a constitutional amendment to neutralize its effects. In a recent poll, 6 in 10 people said they disagreed with Citizens United; 8 in 10 said there was “too much big money” in politics.

Reformers know the success of their long-shot campaign means tapping into that sentiment. Short of a constitutional convention, passing an amendment, for example, requires the support of two-thirds of the House and Senate and the assent of 38 state legislatures. “The challenge is overcoming that skepticism about the amendment,” says Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen. “The only way to do that is to build a movement.”

At the same time, Bopp and his allies continue their push to dismantle the remaining campaign finance laws. Their latest target: the century-old Tillman Act, which bans corporations from donating directly to candidates. Should Tillman fall, companies won’t need PACs, super-PACs, or shadowy nonprofits; they’d simply hand checks to the candidates themselves and could theoretically create innumerable shell companies to skirt the existing $2,500 donation cap.

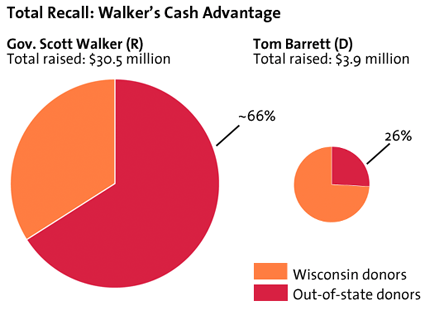

Absent from this struggle is President Obama. After condemning super-PACs, he bent to the post-Citizens United political reality and urged his supporters to give not only to his campaign but to the super-PAC supporting him, Priorities USA Action. (Despite Obama’s blessing, Priorities has come nowhere close to raising as much money as the pro-Romney super-PAC Restore Our Future or Karl Rove’s American Crossroads.) And with his decision to rely solely on private donations in 2008 and 2012 in order to get a leg up on his opponent, Obama has undercut the public financing system created in Watergate’s aftermath. To compete with Obama and appease Republican allies during the last presidential race, John McCain also backtracked on his campaign finance convictions (but ultimately ended up accepting public financing).

Super-PACs, seven-figure checks, billionaire bankrollers, shadowy nonprofits: This is the state of play in what will be the first presidential election since Watergate to be fully privately funded. Faced with this money-drenched system, reformers respond: It won’t last. The pendulum is poised to swing once again. “I promise you, there will be huge scandals,” McCain said in March, “because there’s too much money washing around, too much of it we don’t know who’s behind it, and too much corruption associated with that kind of money.” Russ Feingold, McCain’s longtime legislative partner, agrees. “When this kind of money is changing hands secretly, it’s almost automatic that there will be a scandal,” Feingold says. “And this scandal could be the mother of all scandals.”