<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/13484951@N00/4839739320/">Eric Parker</a>/Flickr

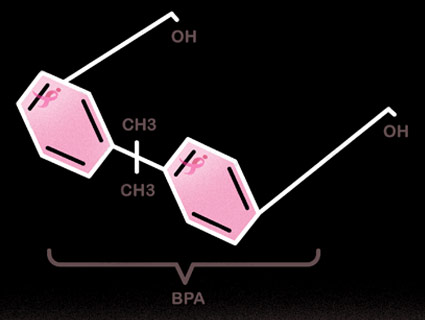

For an industrial chemical released into the environment at more than 1 million pounds a year, it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that bisphenol A also shows up in humans. Four years ago, researchers discovered that BPA, which is used in plastic manufacturing, was present in nearly 93 percent of the US population’s urine.

So it’s disturbing that a growing body of scientific literature suggests that BPA disrupts the body’s hormones. Exposure to the chemical has been associated with risk for obesity, breast cancer, prostate cancer, cardiovascular disease, infertility, diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, and neurological problems.

But the worst part for researchers can be trying to narrow down confounding factors and figure out how BPA makes its way into the body. If these chemicals are everywhere at once—in can linings, soft plastic, as well as leaching into the air and food—how can we even begin to study exposure?

One way is to study people whose lives are isolated from the normal barrage of potential sources. Today, University of Rochester and Mount Sinai Medical Center researchers published a pilot study in journal Neurotoxicology that was conducted with 10 pregnant women from an Old Order Mennonite community in upstate New York. Researchers hypothesized that because Old Order Mennonites—who, similar to the Amish, eschew modern technology—eat more fresh, home-grown foods, don’t use pesticides, and keep personal-care-product and automobile use to a minimum, their levels of industrial chemical exposure would be lower. They were right: Results showed that the median BPA level in the women’s urine was nearly four times lower than the national number.

There are lots of ways to look at these results. One of them, as the Rochester researchers concluded, is the need to emphasize home environment and lifestyle factors in the discussion about exposure to industrial chemicals. Avoiding canned and prepackaged foods, they argue, would be helpful. So would eating organic.

Of course, preaching organic alone hardly addresses the larger issues of social inequality and outsized environmental harms. Earlier this year, a study published in Environmental Health found that concentrations of BPA were 54 percent higher for children who came from families that received emergency food support than for children from families that didn’t. Under circumstances like these, telling people to quit cans and eat organic seems about as effective as telling people living near the equator to quit T-shirts and wear more sweaters. Banning BPA, on the other hand, seems like it could significantly decrease exposure. It’s too bad the FDA still thinks it’s okay to keep BPA in your food.