<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/rauchdickson/554694403/">RauchDickson</a>/Flickr

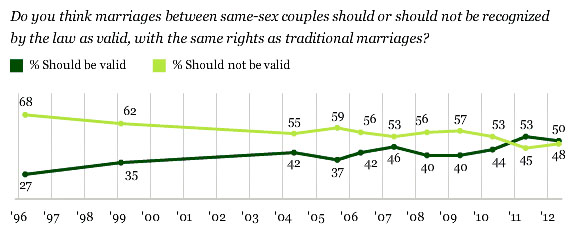

President Obama may support gay marriage, but virtually every time the issue has been put to voters, it’s lost. The most recent example, of course, is North Carolina, where voters overwhelmingly approved a constitutional amendment to define marriage as between one man and one woman. Including North Carolina, 32 states have passed initiatives to ban same-sex marriage in some fashion. But below the surface, the politics of gay marriage are changing. (See chart below.) The ballot initiatives are winning by smaller margins. And gay-marriage ballot measures coming to voters this fall are more likely to be coming from gay rights activists rather than from anti-gay groups like the National Organization for Marriage (NOM).

Gallup polling dataSame-sex marriage activists are putting opponents on the defensive and pushing the issue where attitudes have been changing fast, sometimes in places that just made gay marriage illegal. In Maine, the state legislature legalized gay marriage in May 2009, only to have the law overturned through a ballot initiative six months later. Now, marriage activists are promoting an initiative for the fall that would overturn the overturning. The prospects actually look good, with polls showing that the public generally supports the initiative as written.

Gallup polling dataSame-sex marriage activists are putting opponents on the defensive and pushing the issue where attitudes have been changing fast, sometimes in places that just made gay marriage illegal. In Maine, the state legislature legalized gay marriage in May 2009, only to have the law overturned through a ballot initiative six months later. Now, marriage activists are promoting an initiative for the fall that would overturn the overturning. The prospects actually look good, with polls showing that the public generally supports the initiative as written.

Likewise, in February, the state of Washington passed a law legalizing same-sex marriage but thanks to opposition from groups like NOM, it must go to the voters in a November referendum before taking effect. This year, Minnesota is the only state with a constitutional amendment on the November ballot to ban gay marriage.

Even so, all the activity around the issue, which prompted an unexpected endorsement of same-sex marriage from the president, may be producing a political situation that was all but designed by NOM and its allies to complicate Obama’s reelection strategy. In March, a trove of documents were unsealed in a federal lawsuit filed by the state of Maine against NOM alleging that the group had violated state ethics laws by failing to disclose the donors behind its 2009 ballot-initiative campaign. The docs included a confidential NOM memo explaining that the organization hoped that its “not a civil right” branding could drive a wedge through the Democratic base, dividing black voters and gay liberals, two key constituencies for Obama.

NOM hoped to recruit African American leaders for its campaign and then to provoke gay activists into overreaching and calling those leaders bigots. That’s sort of what happened in North Carolina. NOM funneled lots of money to black churches, whose prominent ministers became leading voices for the passage of Amendment 1. One of the loudest voices came in the form of Patrick Wooden, a notoriously homophobic minister of a 3,000-member black church in Raleigh. (Wooden is obsessed with anal sex and has given some eye-popping interviews on the subject.)

Black voters indeed came out in favor of the anti-gay-marriage amendment, but according to one poll, their support for it actually fell by 10 points, to 51 percent, in the last month of the campaign. This was a sign, perhaps, that the anti-gay forces’ campaign to enlist them might not be entirely successful in the long run. Sharon Lettman-Hicks, a gay activist and executive director of the National Black Justice Coalition, told the Atlantic recently that while “some black clergy have been pulled into this debate, our black churches are smarter than that. They won’t simply be used as pawns to push NOM’s hate.”

Obama can only hope that’s the case. Still, though, it seems unlikely that black voters, 96 percent of whom supported Obama in 2008, would suddenly drop him because of his support of gay marriage, which many of them must have known was coming eventually. After all, the alternative is Mitt Romney, and while he may be an adamant foe of gay rights—Romney donated $10,000 to support NOM’s race-baiting projects—he hasn’t given African Americans many other reasons to vote for him.