Five months ago, the people of South Ossetia, a Georgian breakaway province, cast votes for their next president. Russia—the territory’s controlling nation—had endorsed a candidate, but the majority went instead to former education minister (and anti-corruption advocate) Alla Dzhioeva. But her presidency was short-lived: The Supreme Court declared the election invalid, citing polling violations, and set a do-over election date—from which Dzhioeva was barred from participating. This week, Leonid Tibilov, a former KGB agent, won the new election.

South Ossetia is one of three contested republics in the Caucasus region. Its election chaos illustrates the impasse faced by these territories: All are trying to form autonomous nations, yet they can’t build government without a stamp of approval from one of the only countries in the world that recognizes their nationhood. Their independence depends on Russia’s support.

The Caucasus region, which straddles the Europe/Asia border, houses a medley of religions and ethnicities, from the Indo-European Ossetians to the Christian Armenians and the Muslim Azerbaijanis. During the USSR era, all that barely mattered; the Soviet identity subsumed regional and sectarian differences. But since the Soviet Union’s fall in 1991, rival factions, finally able to assert their singularity, have clashed over competing claims to overlapping homelands.

The first to rise up was Nagorno-Karabakh. The Azerbaijani territory, which is populated largely by Armenians, declared its independence in the thick of the USSR’s December 1991 dissolution. A few months later, South Ossetia—where several Indo-Iranian dialects are spoken—won partial autonomy from Georgia in a bloody war. And they prevailed mostly because Georgia was distracted by the separatist movement in Abkhazia, another breakaway province, which gained independence in a 1992 conflict that claimed nearly 10,000 lives and displaced a quarter million people.

Today, these territories exist in a legal no-man’s land, largely unrecognized by other nations, and often dependent on neighboring states, primarily Russia, for survival. Over two decades, they’ve balanced self-protection with haphazard nation-building. Armed clashes with anti-secessionist forces are frequent, though rarely publicized in Western media.

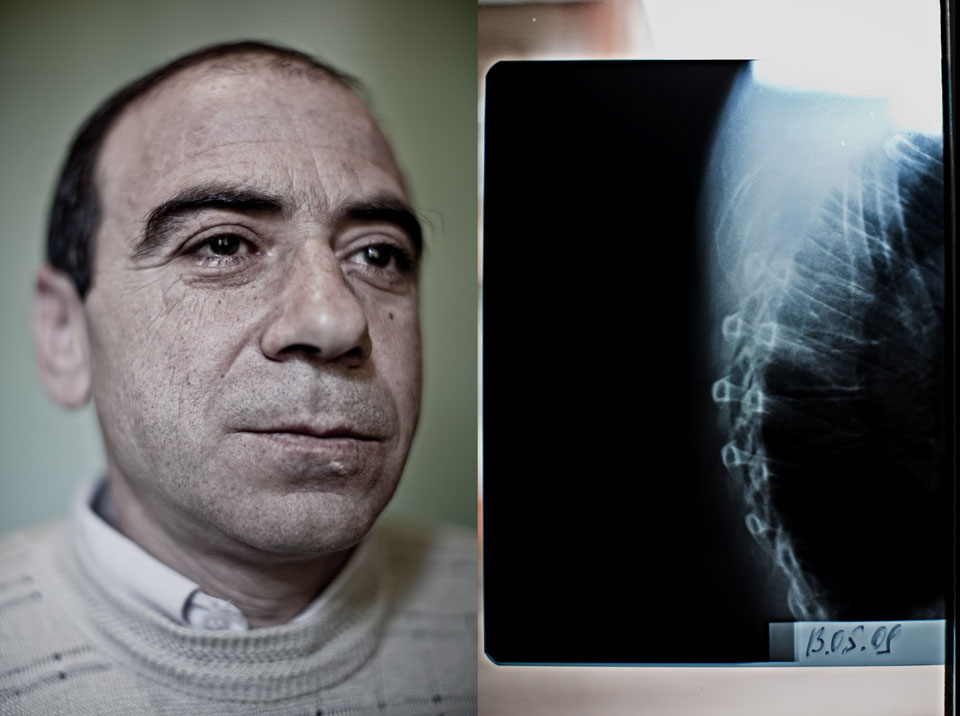

Photographer Karen Mirzoyan spent three years exploring these territories, to expose and understand their singular struggles.

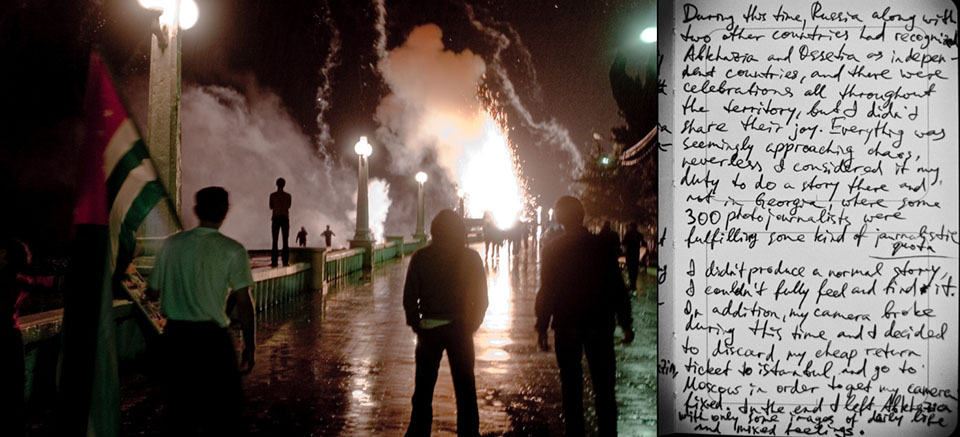

“My aim was to document the transitional state of these unrecognized republics in the region,” he explains. “In the beginning, my task seemed simple. What I did not take into account was that over a period of three years, not only my story, but my way of seeing, was subject to transformation.” He continues:

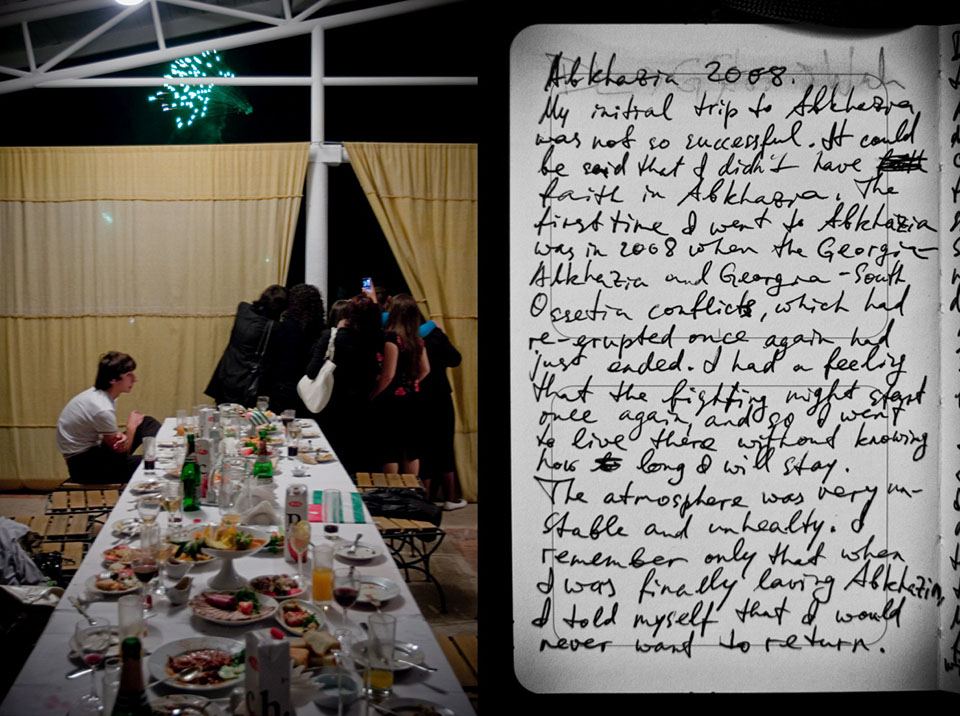

Most frequently I was simply sitting with people over a table, drinking, sharing food and the stories of our lives. I often told them about my family, my aspirations, of my upcoming wedding…in return, they loved and understood me as much as I’d come to love and understand them.

I did not want to compromise a single detail, the smallest nuance of the stories shared for the privilege of turning on a microphone, reaching for my camera or even taking out a pen. So, I was not working, I was not acting as a photojournalist…because when interaction is so warm and intimate, I feel it would be unfair to just take these heart-told stories and package them for retail.

Nevertheless, Mirzoyan did take occasional photographs. But he didn’t depend on them: Mirzoyan also recorded sounds, wrote in notebooks, or sketched subjects who didn’t want to be photographed. “I confess to photography being my excuse, my rationalization for these repeated trips,” he explains. “[But] my aim is not to document. I just wanted to see for myself, to listen and understand.”

This photo essay presents an excerpt of Mirzoyan’s attempt at understanding life in the Caucasus’ transitional pockets.

Part One: The Nagorno-Karabakh War: Past, Present, and Future

Part Two: Abkhazia

Part Three: South Ossetia

Part Four: Karabakh

This project was developed with support from the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund, in partnership with Mother Jones. The Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund supports experienced photographers with a commitment to documenting social issues, working long-term, and engaging with an issue over time.