<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/49264754@N00/5122789120/">TheRealMichaelMoore</a>/Flickr

If you happened to be in downtown San Francisco on the eve of the 1906 earthquake and were in the mood for booze, seafood, and other vices, you couldn’t do much better than coming to the future home of Mother Jones. Today, our building on Sutter Street houses other respectable outfits including an upscale bakery, Loehmann’s, and Craigslist. But back before the great fire obliterated it exactly 106 years ago, this spot epitomized the city’s old, seamy ways.

In 1877, a couple of Canadian brothers, Frank and Jesse Gobey, opened Gobey’s Saloon in the Rose Building at 228 Sutter Street. When Frank Gobey died suddenly at age 56 in 1895, the Chronicle stated that his bar and restaurant was “a notable gathering place for the inhabitants of the ‘tenderloin,’ but as it was always conducted in a quiet and orderly manner it was never the scene of any trouble.” Whether the reporter did not wish to speak ill of the dead or was being sarcastic isn’t clear, but it seems that Gobey’s was anything but staid.

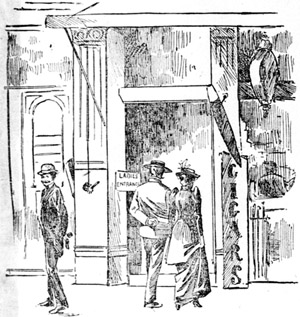

Men could enter Gobey’s Saloon via the door on the far left. Women and their chaperones had to sneak in the back. San Francisco Public LibraryJust a year before Frank Gobey’s death, the saloon was the site of a celebrated incident following the annual “big game” between Stanford and UC Berkeley. As football fans packed the bar, a young swell shot and wounded Stanford player Louis “Brick” Whitehouse and another patron. When the reporters arrived, Gobey was heard telling his staff to “say nothing to no one” about the shooting, much to the chagrin of the police. In 1895, Gobey’s was found to be serving counterfeit champagne, though only the distributor was charged. In 1897, Jesse Gobey was accused of running a nickel slot machine, but was let off.

Men could enter Gobey’s Saloon via the door on the far left. Women and their chaperones had to sneak in the back. San Francisco Public LibraryJust a year before Frank Gobey’s death, the saloon was the site of a celebrated incident following the annual “big game” between Stanford and UC Berkeley. As football fans packed the bar, a young swell shot and wounded Stanford player Louis “Brick” Whitehouse and another patron. When the reporters arrived, Gobey was heard telling his staff to “say nothing to no one” about the shooting, much to the chagrin of the police. In 1895, Gobey’s was found to be serving counterfeit champagne, though only the distributor was charged. In 1897, Jesse Gobey was accused of running a nickel slot machine, but was let off.

Other unsavory goings-on at Gobey’s were hinted at in the press. “There are upper and rear rooms at Gobey’s that could make strange and starting revelations if gifted with speech,” The San Francisco Call winked.

In a July 1893 article titled “Pitfalls for Women. Scenes of Gilded Vice and Squalid Sin,” Call correspondent Marie Evelyn recounted a tour of saloons with a male colleague identified only as “Mr. Y.” At the time, the city’s many drinking establishments were considered off-limits to proper women, yet female companions could enter by way of the “ladies entrances” usually hidden in plain sight. Once inside, patrons could retreat to private, locked booths where men might lead women down “the flowery paths of vice,” as Evelyn put it. “Small wonder if a weak woman’s moral sense grows confused when such perversions are allowed by law,” she wrote.

Evelyn’s descent into the intemperate underworld concluded at Gobey’s:

“What a change from those wretched bars,” I could not help saying with a sigh of relief; “this is quite respectable by contrast.”

“Yes?” replied Mr. Y in a tone of mild interrogation, “you make a distinction between gilded vice and squalid sin? Those rooms have not doors with bolts. If you look through the curtain you will see what nice women are passing in and out to rooms at the back that have doors.”…

“These dens look rather like the staterooms of a first-class steamer,” said Mr. Y. “Don’t you think we should be about right in calling this a cabin passage to the lower regions, and the squalid saloons a steerage one?”

“Nice women are passing in and out to rooms at the back that have doors.” San Francisco CallHer account is echoed in Clarence E. Edwords’ Bohemian San Francisco: “Gobey ran one of those places which was not in good repute, consequently when ladies went there they were usually veiled and slipped in through an alley.” At a police commission meeting in 1900, Gobey’s lawyer “contended that the best people of the town, men with their families and all who wanted a little privacy, patronized these places.” Perhaps he wasn’t entirely exaggerating; as Edwords adds, “the enticement of Gobey’s crab stew was too much for conventionality and his little private rooms were always full.”

“Nice women are passing in and out to rooms at the back that have doors.” San Francisco CallHer account is echoed in Clarence E. Edwords’ Bohemian San Francisco: “Gobey ran one of those places which was not in good repute, consequently when ladies went there they were usually veiled and slipped in through an alley.” At a police commission meeting in 1900, Gobey’s lawyer “contended that the best people of the town, men with their families and all who wanted a little privacy, patronized these places.” Perhaps he wasn’t entirely exaggerating; as Edwords adds, “the enticement of Gobey’s crab stew was too much for conventionality and his little private rooms were always full.”

Gobey’s was also credited as the source of the oyster loaf (sorry, New Orleans*)—a thick hunk of crusty bread hollowed out and stuffed with breaded and fried oysters. Noting that San Franciscans who had emigrated from the Atlantic seaboard had a “hankering for succulent and enormous bivalves,” a 1926 article in The San Franciscan explained that “after a night with the boys, they felt the urge to placate the lady of their heart with a tid-bit and the Chinaman at Gobey’s saloon thought up a oyster loaf.” (The dish was also rumored to be an ideal “peacemaker” for delinquent husbands to offer to annoyed wives: “The deliciously flavored steam ascends like sweet incense until it reaches her rigid nostrils, and then her stern features relax into something like a smile.”)

The ladies’ entrance to Gobey’s likely opened onto Mary Lane, one of several alleys behind the Rose Building. One of them, the serendipitously named Clara Lane, may have been an even more colorful (and tragic) site than the saloon:

May 1867: The owner of a building on the corner of Sutter and Clara Lane writes the Daily Alta California to clarify that an illegal liquor still had not been found on his property, but in an adjacent building. He insisted that the alleged distiller claimed to be setting up a “vinegar factory.”

August 1884: Eleven-year-old Philomena Fry falls into Clara Lane while trying to pick some flowers from a window box three stories above.

April 1886: An item in The Call reports that “Wallace McCreary, an old-time opera singer, allowed his feelings to overcome him about 8 o’clock yesterday morning and took a tumble from a second-story window in the rear of the building occupied by Sam Sample’s saloon, on Kearney street. McCreary landed on the stone pavement of Clara lane and sustained a severe contusion on the back of his bead, but nothing of a serious nature.”

January 1887: A man who absconded with another’s five-gallon can of gasoline is apprehended in the alley and positively identified as “Smoothy, the cocaine fiend.” The same month, one Clara Mason of Clara Lane is admitted to the hospital for “an overdose of strychnine self-administered.”

Cocaine fiends, falling bodies, and stabbings: Just another day in Clara Lane David Rumsey Map Collection

April 1887: Sixteen-year-old George Murphy survives being shot at after a quarrel with some men leaving the Fern Leaf Saloon. The suspect makes his escape down Clara Lane to Sutter Street.

November 1887: The Call briefly recounts the tale of Celso Garcia, a bootblack who said he’d been cut on the nose when “Arvilo Venartiar, a tamale peddler, had entered his house at 6 Clara lane and started in to carve him and his wife Maria up because Venartiar’s attentions to Garcia’s daughter did not meet the parental approbation.”

January 1888: Carrie (Clara?) Mason of Clara Lane is reported to have been hospitalized “suffering from a dose of chloral hydrate.” The Call notes, “This is the second time within a few months that the woman has attempted to solve the problem of how much chloral it would take to kill her. Abusive treatment on the part of her husband is stated to be the cause of her attempted suicide.”

September 1904: A newspaperman is attacked while walking down Clara Lane late at night. The Call reports: “He was cut over the left eye, across the bridge of the nose and over the right ear. The wounds were apparently inflicted by a dull instrument.”

The 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed 490 square blocks of the city, including this stretch of Sutter Street. Gobey’s reopened nearby, but was said to be a shadow of its former self. Clara Lane became Claude Lane; Mary Lane is now Mark Lane. Smoothy the coke fiend and trigger-happy football fans have been replaced by 9-to-5ers and shivering tourists. But the MoJo building still has a rear door, possibly in the same spot where the ladies’ entrance to Gobey’s once welcomed anyone looking for a drink, a date, or a bite of oyster loaf.

* The New Orleans Times-Picayune‘s Brett Anderson convincingly counters this crusty claim: “There is proof New Orleanians were eating sandwiches called oyster loaves and peacemakers before Gobey’s ever hosted its first scene of gilded vice and squalid sin.