Obama at a San Francisco campaign rally in 2011<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/barackobamadotcom/5655674841/">Barack Obama</a>/Flickr

This story first appeared on the ProPublica website.

Last Thursday, President Obama’s re-election campaign sent out an email blast to supporters. Former journalism professor Dan Sinker and his wife received their emails simultaneously, as they sat next to each other on their couch in Chicago. Both emails were from Julianna Smoot, the deputy manager of Obama’s campaign, and both asked for donations.

Sinker’s email asked him to help the campaign try out a “new, super-easy” online donation tool by giving $20.

The email to his wife, by contrast, described a 61-year-old mother and grandmother whose donation had just won her a seat at a dinner with the president. It asked for $25.

Sinker and his wife weren’t the only ones to receive similar but subtly different emails from the Obama campaign. Responding to a call on Twitter from Sinker (and another from us), 190 people from 31 states and Washington, DC, sent us the messages they received.

A look at those emails shows the campaign sent out at least six distinct versions of the fundraising appeal.

The reasons for the differences remain unclear. (The campaign hasn’t responded to our requests for comment.) It could be the campaign testing which phrasing gets the best response. The messages may also be tailored to individual voters based on the campaign’s extensive database of personal information.

Either way, it’s a glimpse into the detailed data work that rarely gets attention but is increasingly central to campaigns.

You can take a look for yourself. We have posted an interactive allowing you to track the differences among the emails.

The changes are small, but may highlight the ways that political campaigns are increasingly tailoring their messages—and their funding requests—using personal information about potential voters. While appeals to specific voters have long been a part of campaigns, politicians now have the ability to “microtarget” voters based on everything from their donation history to what religion they list on Facebook.

Voters have little way of knowing how much a campaign knows about them, how the messages they’re receiving differ from the messages a campaign is sending other voters—or what these differences might reveal about the campaigns’ priorities.

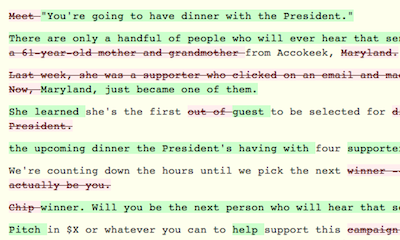

From ProPublica’s analysis of Obama campaign emails

From ProPublica’s analysis of Obama campaign emails

Sasha Issenberg, a journalist who has done extensive reporting on campaigns’ new uses of data and analytics, said the Obama campaign is leading the way. It takes a rigorous approach to testing the effectiveness of different messages, tracking results based not only on the message content, but also the name given as the sender of the email, the subject line, the format, even the date and time of day the messages are sent.

“People who don’t get an email on Thursday, might be because they didn’t respond to emails on Thursdays in the past,” said Issenberg, who is writing a book about campaign data use. “Every element of an email is a potential variable.”

While the Obama campaign is usually perceived as the most data-savvy, Mitt Romney‘s and Rick Perry’s campaigns have also used microtargeting tactics to reach specific voters through email, Facebook, and online ads and video.

“We’re all seeing different campaigns play out,” Sinker said.