<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/truthout/4150828177/">Truthout.org</a>/Flickr

This story first appeared on the ProPublica website.

The Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision opened the way for unlimited corporate spending on politics and has led to the proliferation of nonprofit political groups that do not have to disclose the identities of their donors. But corporations may be getting another benefit from anonymous donations to these groups: a break on their taxes.

It all starts with the so-called social welfare groups that have become bigger players in the political world in the wake of Citizens United, which knocked down restrictions on campaign activity by such groups.

Tax experts say it’s possible that businesses are using an aggressive interpretation of the law to wring a tax advantage out of their donations to these groups.

It’s almost impossible to know whether that’s happening, partly because the groups—also known by their IRS designation as 501(c)(4)s—aren’t required to disclose their donors. (That’s why the contributions have been dubbed “dark money.”)

This state of affairs is not entirely new; social welfare groups have long been involved in politics. In 2000, for example, the NAACP National Voter Fund, which is a social welfare group, ran hard-hitting ads just days before the election criticizing George W. Bush for his opposition to hate-crime legislation. What’s new is the scale of such groups’ election involvement, which has expanded dramatically in the wake of Citizens United and helped feed the increasing flood of money in elections.

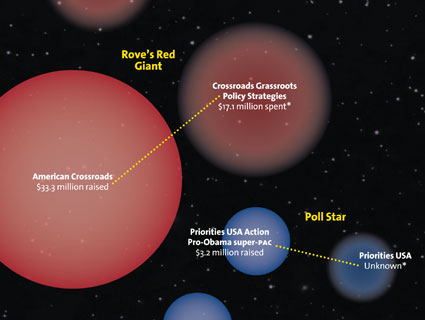

The most prominent of a new crop of these groups is the Karl Rove-affiliated Crossroads GPS, which raised $43 million for the 2010 midterm elections and is expected to become an even bigger force this year. It has pledged to raise and spend $300 million with its sister super PAC, American Crossroads. Democrats also are expanding their use of these groups, led by the pro-Obama Priorities USA, which raised $2 million last year.

Precisely because they offer anonymity, such groups may be attractive vehicles for companies that want to spend money electing a favored candidate or pushing an issue. In 2010, Target generated a national backlash after giving $100,000 to a Minnesota group that ran ads supporting a candidate who opposed gay marriage. Liberal activists seized on the donation after it was revealed in state filings. If Target—or any other public or private corporation—gave to Crossroads GPS or Priorities USA, the public would never know.

Companies also may be deducting from their taxes the undisclosed donations to these groups.

“There has always been this suspicion, but I can’t prove it,” says Frances Hill, a tax law professor at the University of Miami who first floated the concept in a brief mention in The New York Times earlier this month. “It could be put into the advertising budgets, which for many companies are very large dollar amounts.”

This is where the aggressive interpretation of the tax code would come into play.

Corporations are allowed wide latitude in deducting business expenses from their taxes—everything from workers’ salaries to marketing expenses of all kinds. But one thing they’re explicitly barred from deducting is political expenditures.

As the law puts it, companies are not allowed to deduct money spent on “intervention in any political campaign” or “any attempt to influence the general public, or segments thereof, with respect to elections, legislative matters, or referendums.”

But tax experts say a company could argue that money given to “social welfare” groups isn’t political spending at all and that the donations are instead “ordinary and necessary” business expenses.

The company might argue, for example, that ads by a social welfare group would favorably influence opinion on a public policy issue that affects the company’s business. Thus, say, an oil company would claim a business expense deduction on a donation to a social welfare group that was running ads criticizing President Obama’s policies on domestic drilling.

The company also would have to argue that the money wasn’t being used by the groups on political expenditures. So, it comes down to where the IRS draws the line on defining a political expenditure, and whether ads run by such groups as Crossroads GPS or Priorities USA cross the line.

Defining a political expenditure is a matter of intense dispute. The IRS has historically looked at various factors in assessing nonprofit spending, such as whether an ad mentions a candidate for public office or is aired close to an election. But wiggle room remains.

“It’s a smell test,” says Lloyd Hitoshi Mayer, a Notre Dame professor who specializes in election and tax law. Donor corporations’ lawyers “could take the position that unless an ad is express advocacy, it’s not across the line for tax purposes.” Under this argument, an ad praising Obama’s stance on foreign policy wouldn’t be classified as political unless it explicitly told viewers to “vote for Obama.”

The social welfare groups themselves also have an interest in classifying their work as issue-based or educational since they risk losing their tax status if their primary purpose is political campaign activity. Campaign-finance reformers have been pressing the IRS to crack down on the new social welfare groups that, they argue, are abusing their tax status.

“The organizations themselves may be arguing that their expenditures are not political, they are issue advocacy. If you accept that characterization, you would get a deduction,” says Marcus Owens, a partner at Caplin & Drysdale and former director of the IRS’ Exempt Organizations Division.

Crossroads GPS and Priorities USA did not respond to requests for comment about the proportion of their work that they classify as political. The proportion matters because if corporations are, in fact, deducting donations as business expenses, they cannot deduct the part of the donation that was used for political purposes.

So, where does all this leave us? If a company gave $1 million to Crossroads GPS or Priorities USA and claimed the donation was a business expense, that would be $1 million of the company’s revenue not subject to taxes. If the company was paying a 30 percent tax rate, that would mean savings of $300,000.

But this is entirely hypothetical because we can’t be sure whether this tax strategy is occurring. First, the social welfare groups don’t reveal their donors. So, we don’t know which companies to ask about the deduction issue. And if companies are taking the deduction, it would be detailed in tax returns that are confidential.