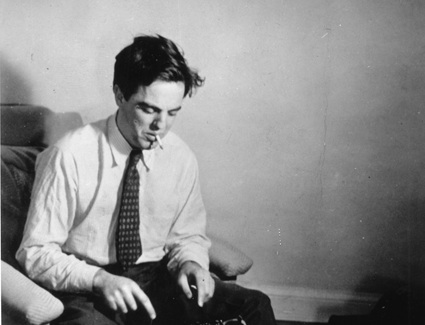

Alan Lomax, circa 1942.Courtesy of the Association for Cultural Equity

In an age where Justin Bieber can skyrocket to the highest heights of pop consciousness thanks to a couple well-placed YouTube videos, we’ve forgotten how hard it once was to spread popular music to the populace it described. In the 1930’s and ’40’s, while Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, and others were crafting the folk songs that laid the foundation for uniquely American styles like rock and roll and the blues, they mostly sang in obscurity to local audiences in the country quarters where they lived. Recording equipment was bulky, fragile, and expensive, and those who could afford access to recorded music were listening mostly to European imports and early jazz. Thus, the music that best captured the lives of workaday Americans could only be heard by lucky locals in small-town dance halls and living rooms.

Enter Alan Lomax, an upstart folklorist who in his early teens began to accompany his father John on expeditions across the country, recording the songs of poor farmers, prisoners, bar musicians, and others whose music would otherwise have faded like a melody in the wind. Lomax’s road stories are captured in a book by Columbia University musicologist John Szwed’s Alan Lomax, to be released in paperback tomorrow.

Courtesy Penguin

Courtesy Penguin

Lomax was born on the outskirts of Austin in 1915, into a family that worked on the fringes of Unversity of Texas academia; his father made his career collecting the songs of Texas cowboys. Until his death in 2002 at the age of 87, Alan Lomax produced thousands of field recordings, many specifically destined for the Library of Congress, and was the first to “discover” Guthrie, Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Jelly Roll Morton, and Son House, among other folk musicians revered today. They were progenitors of the singer-songwriter type we know so well today, leaving an incalcuable impact on everyone from Bob Dylan to Kurt Cobain to Jack White.

But the real import of Lomax’s work goes beyond bringing backwoods folk singers into the limelight. At the heart of his mission was a fervent belief in the democratizing effect of folk music. The real point of lugging recording equipment over praries, swamps, and mountains was to capture the voices of “miners, lumbermen, sailors, soldiers, railroad men, blacks, and the down-and-outs, the hobos, convicts, bad girls, and dope fiends,” and bring their stories, wrapped in song, to the ears of middle- and upper-class whites. America “was hungry for a vision of itself in song,” Szwed writes, and Lomax was determined to feed it.

Lomax bounced between the University of Texas and Harvard for a few years, but mostly learned his craft on the road with John, who had imbued his son from birth with a love of and respect for folk music. Their tour schedule was demanding: in a tiny car packed to the gills with blank records and a mess of recording equipment, they drove from town to town across the country, especially the South, for months at a stretch. At each stop they would beeline for the local clerks, academics, and prison wardens and asked to be led to wherever music was being made in town: chain gangs, makeshift bars, logging camps, front porches. They faced malaria and shotguns, but often found music by simply walking through poor black neighborhoods and listening through open doors.

Most of their recordings were dispatched to the Library of Congress, which had funded much of the Lomax’s collection effort, sporadically employed Alan and granting him entee to the upper-crust circles he hoped to interest with his musical findings. In the beginning, the recordings were seen merely as curious artifacts, but soon recording companies began to take notice, and Lomax realized the potential of his recordings to build cultural appreciation and understanding between whites and blacks and rich and poor. He began to publish sheet music and records for a wider audience.

In Lomax’s philosophy, a more democratic society starts with the democratic creation of culture. Music created and distributed by the “folk,” he argued, was the direct line for oppressed groups to register their complaints with the powers-that-be. “We must show social conditions, not just songs,” Lomax said of his collection efforts (eventually landing on the FBI’s watch list for potential Communists). In this year of Occupy and the Arab Spring, where mass movements mushroomed across social media networks, it’s clear he was onto something (though some musicians have bemoaned the lack of a definitive protest song for the Occupy movement).

Moreover, the folk songs Lomax popularized (many of which were older tunes with updated, topical lyrics) gave political credence to the angst of the down-and-out by drawing a connection to “an American tradition of resistance and struggle that had been buried by time, neglect, and misrepresentation.” The songs delivered stories of hardship and oppression directly to Washington pols, New York intellectuals (including the popular salon at Lomax’s Greenwich Village apartment), and others who would never have listened otherwise.

In 1934, Lomax got word that Lead Belly, a skilled guitarist with a rolling, unsettling tenor who later became a close friend and roadie for Lomax, was being released from the Louisiana prison where he’d been serving long, hard time for an ancient (and probably trumped-up) murder conviction. Lomax had first heard Lead Belly on a chain gang there years before, and had always prized the recording he’d made as one with the most power to turn the heads of white elites. Lomax sent him a note that, in his philosophy, serves as the ultimate advice to anyone wanting to right some wrongs and earn some well-deserved respect: “Come prepared to travel. Bring guitar.”