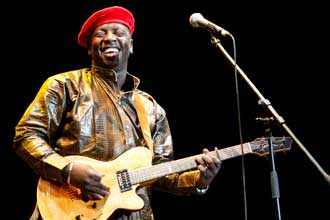

Photo by Andrew Glaser

Tinariwen sound-checks like any other band: Musicians filter onstage one at a time, adjust knobs, tune up, play little melodies. It’s a scene of subdued chaos, like the pleasant cacophony that precedes a classical orchestra performance. But the last musician to step into the soft blue stage lights of Bimbo’s 365 Club in San Francisco isn’t noodling. A faded old Fender Telecaster hangs from frontman Ibrahim Ag Alhabib’s shoulder, but for now it’s silent. His dark eyes stare absently out at the empty hall from under a shaggy Jimi Hendrix mane. The look says, “I’m here, but I’m a million miles away.”

Really, it’s more like 6,000 miles: Tinariwen hails from the harsh, windswept deserts of northern Mali, and despite a decade touring the world the band is still fixed—musically, spiritually, politically—to that spot. Watching the group perform early this month was like experiencing a hallucinatory mirage; intellectually I knew I was in San Francisco, but all my senses told me I had landed somewhere deep in the Sahara. This is the central irony of Tinariwen: that a band that so keenly communicates a sense of place could be formed by members of the nomadic Tuareg people, who have for centuries (and still today) wandered restlessly through the desert with nothing but a few belongings and a fierce disdain for anything remotely static—including the Malian government.

It was that disdain that first brought the musicians together in a 1980s Libyan military training camp (sponsored by now-fugitive dictator Moammar Qaddafi), which prepared them to take up arms in an early-’90s Tuareg rebellion against the Malian state. It’s been years since they traded guns for instruments, but bassist Eyadou Ag Leche told me the band sees itself as the voice of a people who still feel marginalized.

“Music is a way for us to share our story with people around the world,” Ag Leche said, in French. (The band members speak no English; they sing in French and Tamashek, their native tongue.)

It’s the painful story of a distressed culture, but over the years Tinariwen has become deft at telling it. They were given a 2005 BBC World Music Award, and have garnered praise from the likes of Robert Plant (who described the band as “the music I’d been looking for all my life”), as well as Carlos Santana. This week, the band’s fifth album, Tassili, comes out on the Anti- label. It features collaborations with members of TV on the Radio, Wilco, and the Dirty Dozen Brass Band. The album is gorgeous, with everything from stirring, ghostly ballads like “Walla Illa” to signature thumping dance numbers like “Tenere Taqhim Tossam” (see video), where TV on the Radio vocalist Tunde Adebimpe’s high-pitched wails cut through a sound that is usually dense and bass-heavy.

In San Francisco, Tinariwen opened its set gingerly, as if afraid to pull out all the stops in front of a small audience. It felt almost like waking up, or watching the sun slowly rise over a crusty desert outcrop. That feeling lasted about three songs, at which point percussionist Mohammed Ag Tahada shattered the stillness with a resounding djembe slap, using a force that would split most hands. The drumming was joined by a chorus of claps and ululations that kicked off what would become a three-hour musical trance. It was still impossible to tell what continent I was on, and it didn’t matter.

Tassili is the group’s the first album that includes contributions from non-Tuaregs, but that doesn’t mean the band is straying from its roots. Quite the opposite: The album was recorded in the desert, with all acoustic instruments and portable generators for the recording equipment. Not surprisingly, there were some technical difficulties: There were sand-choked amplifiers, power was spotty, and keeping the wind noise off the tracks was damn near impossible.

Ag Leche told me that the band took it in stride; after all, this where they’ve been playing music all their lives. “For us, it’s the same to organize this in the desert as it is for anyone to record in a big studio,” he said. “We know the conditions in the desert.”

Those conditions forced the recording operation to relocate frequently; the band would set up, try a spot out, then move on. Sounds like a pain, but moving around is what the Tuareg do best. Even in music, it seems, phylogeny recapitulates ontology: To tell the story of a nomadic people, the music must be nomadic as well. Here’s Tinariwen in action:

Click here for more music features from Mother Jones.