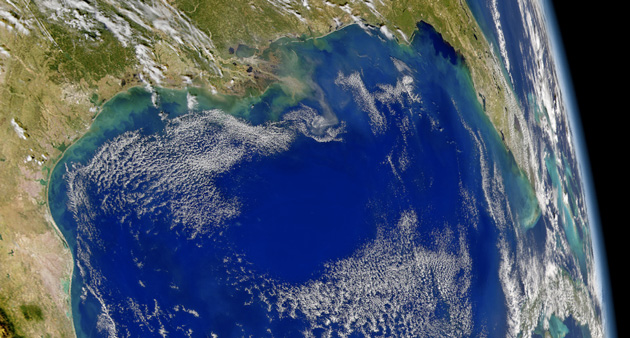

The Gulf of Mexico. NASAThis year’s hypoxia forecast forecast calls for the largest dead zone yet seen in the Gulf of Mexico. The report’s just been released by the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, aka LUMCON:

The Gulf of Mexico. NASAThis year’s hypoxia forecast forecast calls for the largest dead zone yet seen in the Gulf of Mexico. The report’s just been released by the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, aka LUMCON:

This [dead] zone continues to threaten living resources including humans that depend on fish, shrimp and crabs. Excess nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, cause huge algae blooms whose decomposition leads to oxygen distress and even organism death in the Gulf’s richest waters.

I thought it might be interesting to take a look at the full lineage of this unfolding disaster—starting with the polar jet stream.

![Compare the position of the polar jet stream [purple] in these images of a typical El Niño and a La Niña, with the jet further south for La Niña. : NOAA/Wikimedia Compare the position of the polar jet stream [purple] in these images of a typical El Niño and a La Niña, with the jet further south for La Niña. : NOAA/Wikimedia](https://motherjones.com/wp-content/uploads/images/2r.preview.jpg) Compare the position of the polar jet stream [purple] in these images of a typical El Niño and a La Niña, with the jet further south for La Niña. NOAA/Wikimedia

Compare the position of the polar jet stream [purple] in these images of a typical El Niño and a La Niña, with the jet further south for La Niña. NOAA/Wikimedia

There’s been an unusual La Niña-type jet stream dipping dip far south all through the spring. Jeff Masters at WunderBlog explains:

La Niña alters the path of the jet stream, making the predominant storm track in winter traverse the Midwest and avoid the South… La Niña’s influence on the jet stream and U.S. weather typically fades in springtime… However, in 2011, the La Niña influence on U.S. weather stayed strong throughout spring… with wind speeds more typical of winter than spring… A series of strong storms moved along the jet stream and pulled up warm, moist Gulf of Mexico air, which mixed with the cold air spilling south from Canada.

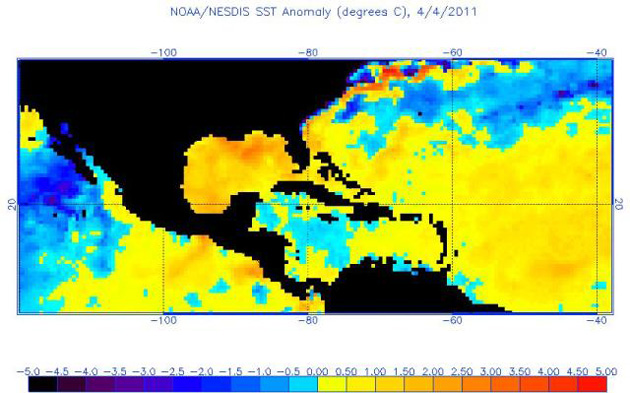

Sea surface temperature anomalies on 4 April 2011. NOAAThat collision of air masses spawned a lot of precipitation—particularly because of this year’s warmer-than-normal waters in the Gulf of Mexico. Masters continues:

Sea surface temperature anomalies on 4 April 2011. NOAAThat collision of air masses spawned a lot of precipitation—particularly because of this year’s warmer-than-normal waters in the Gulf of Mexico. Masters continues:

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Gulf of Mexico warmed to 1°C (1.8°F) above average during April—the third warmest temperatures in over a century of record keeping… These unusually warm surface waters allowed much more moisture than usual to evaporate into the air, resulting in unprecedented rains over the Midwest when the warm, moist air swirled into the unusually cold air spilling southwards from Canada. With the jet stream at exceptional winter-like strengths, the stage was also set for massive tornado outbreaks.

Above: North Dakota, 12 Dec 2010. Below: swollen lower Mississippi River, 1 June 2011. NASAIn the two images above, taken six months apart, you can see how winter’s heavy snows, pounded by spring’s heavy snowmelts and ongoing heavy rains, changed the Mississippi landscape… and—ultimately—the seascape.

Above: North Dakota, 12 Dec 2010. Below: swollen lower Mississippi River, 1 June 2011. NASAIn the two images above, taken six months apart, you can see how winter’s heavy snows, pounded by spring’s heavy snowmelts and ongoing heavy rains, changed the Mississippi landscape… and—ultimately—the seascape.

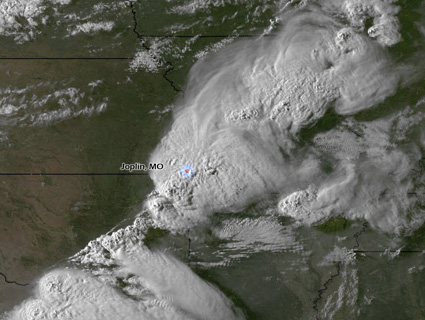

Mississippi River sediment in the Gulf of Mexico. NASAThe problem—as I wrote earlier—is all the stuff in the floodwaters that isn’t riverwater, namely fertilizers and other enrichers, like manure, which are the drivers behind the dead zone.

Mississippi River sediment in the Gulf of Mexico. NASAThe problem—as I wrote earlier—is all the stuff in the floodwaters that isn’t riverwater, namely fertilizers and other enrichers, like manure, which are the drivers behind the dead zone.

Put the weather, the floods, the farms, and the poo together and you get LUMCON’s particularly gloomy hypoxia forecast:

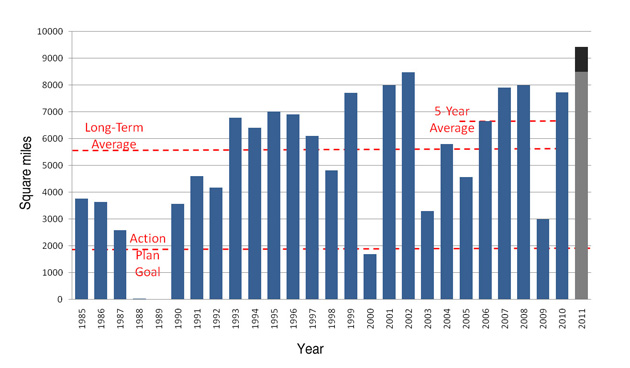

The June 2011 forecast of the size of the hypoxic zone in the northern Gulf of Mexico for July 2011 is that it will cover between 22,253 to 26,515 km2 (average 24,400 km2; 9,421 mi2) of the bottom of the continental shelf off Louisiana and Texas. The predicted hypoxic area is about the size of the combined land area of New Jersey and Delaware, or the size of Lake Erie. The estimate is based on the May nitrogen loading (as nitrate+nitrite) from the Mississippi watershed to the Gulf of Mexico estimated by the U.S. Geological Survey. If the area of hypoxia becomes this large, then it will be the largest since systematic mapping of the hypoxic zone began in 1985.

Long-term measured size of Gulf of Mexico hypoxic zone with 2011 forecast. Dark gray represents the range of ensemble forecast. Nancy Rabalais LUMCON/NOAAThus an initial problem with farmers incidentally fertilizing the ocean unto death is now compounded by a rapidly-shifting climate locked and loaded with unpredictable and wild extremes. As Jeff Masters writes:

Long-term measured size of Gulf of Mexico hypoxic zone with 2011 forecast. Dark gray represents the range of ensemble forecast. Nancy Rabalais LUMCON/NOAAThus an initial problem with farmers incidentally fertilizing the ocean unto death is now compounded by a rapidly-shifting climate locked and loaded with unpredictable and wild extremes. As Jeff Masters writes:

One thing we can say is that since global ocean temperatures have warmed about 0.6°C (1°F) over the past 40 years, there is more moisture in the air to generate record flooding rains. The near-record warm Gulf of Mexico SSTs this April that led to record Ohio Valley rainfalls and the 100-year $5 billion+ flood on the Mississippi River would have been much harder to realize without global warming.

The growing dead zone would be slower to realize without global warming too… Another entanglement in the double helix connecting land to air to sea.

Jerome Walker, Dennis Myts/Wikimedia Commons.

Jerome Walker, Dennis Myts/Wikimedia Commons.

Crossposted from Deep Blue Home.