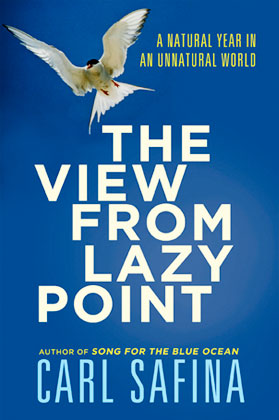

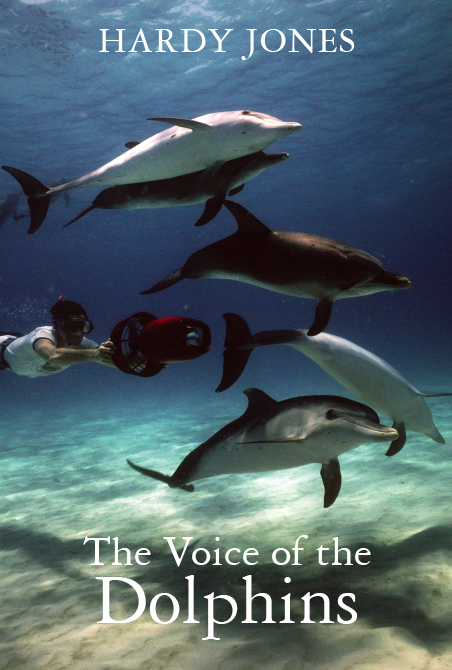

In his newly released book, The Voice of the Dolphins, filmmaker Hardy Jones reports his story of a life spent working with dolphins—working to understand them and working to save them.

Ultimately, and with a sad irony, this dolphin work proves important to Hardy’s own survival. He writes:

This memoir covers three phases of my more than thirty years spent among dolphins and other sea creatures: my initial, exhilarating encounter with friendly dolphins; my subsequent discovery that these creatures are mortally threatened by both slaughter and the chemical contamination of our oceans; and, finally, my diagnosis with a form of blood cancer that has clear links to the same chemical toxins that are causing disastrous consequences among dolphins.

Like all love stories, Hardy’s story with the dolphins—Atlantic spotted dolphins in the Bahamas, spinner dolphins in Hawaii and Tahiti, orca in the Pacific Northwest and Norway, to name a few—is full of beauty, discovery, and wonder. The book resonates with these passages. Here Hardy describes swimming for the first time in the wild with dolphins who did not flee him… a feat even Jacques Cousteau considered impossible in 1978 when Hardy pulled it off.

Dolphins raced at me from all directions, their eyes wide and bloodshot with excitement. The sea was a cacophony of breaking waves, my own gasping, yells, outboard motors, and the creaky-door buzzing of dolphin sonar. Whenever I surfaced, I tried to get some idea of how the filming was going, but no one was even remotely coherent. Words tumbled out of ecstatic faces…

I made a surface dive and swam down among a mixed group of juvenile and adult dolphins, blending into their formations, banking and turning in mid-water. It seemed I had no need to breathe, that I’d assumed properties of a dolphin just by being among them. When my air did run out, I clawed my way back to the surface and gasped for breath, often to find a trio of dolphins accompanying me.

Atlantic spotted dolphins. Credit: Bmatulis via Wikimedia Commons.

Atlantic spotted dolphins. Credit: Bmatulis via Wikimedia Commons.

But like many love stories, Hardy’s with the dolphins is also full of pain and sickness. In 1979 he went to Japan to film the slaughter of dolphins. This was the first of many trips to talk, listen, and argue with the fishermen in defense of the dolphins—all done decades before The Cove filmmakers got there. Hardy writes of being haunted by the two irreconcilable dolphin worlds he’d come to know:

Again and again, especially in early morning hours when I couldn’t sleep, my thoughts returned to the brutal images of dolphins piled on the beaches of Iki… I placed an aerial photograph of the dead dolphins littering the beach at Iki on my desk. Next to that photograph, stood a framed print of two dolphins, looking at me as we swam side by side in the turquoise waters of the little Bahama Bank.

His first film on the dolphin slaughter in Japan was called Island at the Edge—a masterpiece of restrained, elegant reporting. But that was only the beginning. He writes:

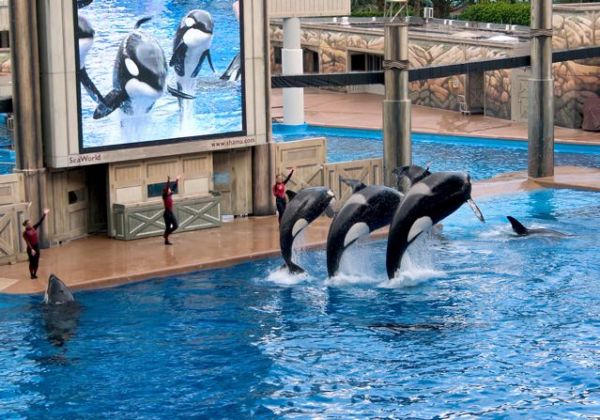

In the course of my travels to Japan, I’d come to realize that… a major part of the incentive to local fishermen to pursue and kill dolphins is cash put on the table by international dolphin traffickers who come to Taiji to pick out “show-quality” dolphins. They pay enormous amounts, as much as $150,000 for a dolphin trained in Taiji. The service includes trainers who will accompany the locally trained dolphin to its final destination in one of the many dolphinaria in Japan, as well as to China, Korea, French Polynesia, Turkey and Egypt. For dolphins, this must be the equivalent of an alien abduction. The captive dolphins eventually end up in a cement tank performing for fish in aquarium shows and “swim-with-dolphins” programs around the world.

Shamu Stadium, SeaWorld. Credit: David Bjorgen via Wikipedia.

Shamu Stadium, SeaWorld. Credit: David Bjorgen via Wikipedia.

From stories of the brutal dolphin entertainment industry, Hardy was eventually drawn into other problems, including the monumental tragedy of six million dolphins drowned in tuna nets. His film If Dolphins Could Talk helped tip that story in a new direction.

When the show hit the air, the results were explosive. The emotional impact of the footage was amplified by a short PSA hosted by George C. Scott that included a 900 number, produced for the show by Stan Minasian of the Marine Mammal Fund. The result was a pile of six thousand telegrams hitting the desk of the chairman of Starkist tuna demanding an end to catching tuna by setting nets on dolphins. Within weeks, Starkist announced that it would no longer accept tuna caught on dolphin. The dolphin-safe label was born and is today overseen by Earth Island Institute and the Marine Mammal Fund. My film synergized with years of hard work by several organizations and was a major conservation victory.

Credit Okeanis, courtesy Hardy Jones.

Credit Okeanis, courtesy Hardy Jones.

In 2003, Hardy was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a rare blood cancer. A few weeks later, he was offered an exciting film project with the PBS series Nature. The film that would eventually come to define him was called The Dolphin Defender.

In follow-up conversations with [PBS], we mapped out the general shape of the film that would be an episodic journey through my career of making films about dolphins. It would combine archival footage shot over a period of several decades with newly shot footage that would fill in gaps in the story and bring it up to date… I hadn’t looked at a lot of that old film for years, and as I started to screen bits and pieces, memories flooded back with a combination of exhilaration, nostalgia, and not a few thoughts of how young I looked. The reaction was, no doubt, intensified by my new-found sense of mortality.

Amazingly, Hardy eventually discovered that his rare disease was not rare in dolphins. Investigating further, he found that places where dolphins were suffering were also myeloma hot-spots for people.

But I’ll leave the rest of that amazing chapter of Hardy’s story for you to read.

Mother and calf bottlenose dolphins. Photo by M. Herko, courtesy NOAA, via Wikimedia Commons.

Mother and calf bottlenose dolphins. Photo by M. Herko, courtesy NOAA, via Wikimedia Commons.

There are a lot of old friends in Hardy’s book, and many facile sketches of others in that strange realm where dolphins, diving, and filmmaking intersect. I’m there too, because Hardy and I worked together for 20 years making nature documentaries. I shared many of the adventures and some of the horrors he describes in The Voice of the Dolphins.

After more than three decades, Hardy’s relationship with the dolphins he loves and admires has mellowed. You can get a sense of that in this clip (below) from BlueVoice.org—Hardy’s nonprofit dedicated to fighting to end the slaughter of dolphins and to exposing levels of toxins in the marine environment harmful to marine mammals and humans. Hardy included.

So buy the book. It’s vivid, vibrant, impassioned, generous, inspirational, and packed with one good sea yarn after another. Best of all The Voice of the Dolphins is loaded with dolphins—old friends with names and personalities and great stories that only Hardy can tell on their behalf.

Among Dolphins from BlueVoice.org on Vimeo.