In January, Mother Jones‘ human rights reporter Mac McClelland and I went to Haiti to report on the rebuilding effort a year after the big earthquake. Two days before we were scheduled to return home, Haiti’s notorious dictator Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier made a surprise appearance in Port-au-Prince after 25 years of exile. Why was he there? Would riots break out? On the ground, no one knew, and we extended our stay to cover the ex-president’s return. What follows is a photographer’s diary of events.

Obama and Duvalier keychainsIn Haiti. We stop at a gas station on a low-key day. Plastic Obama and Duvalier keychains dangle next to Slam condom boxes and cheap razors. One keychain sports double Docs: Baby Doc’s face on one side, Papa Doc’s on the other. Worth a quick shot. A foreshadowing of what’s to come?

Obama and Duvalier keychainsIn Haiti. We stop at a gas station on a low-key day. Plastic Obama and Duvalier keychains dangle next to Slam condom boxes and cheap razors. One keychain sports double Docs: Baby Doc’s face on one side, Papa Doc’s on the other. Worth a quick shot. A foreshadowing of what’s to come?

Sunday evening. I’m sitting on our hotel porch after a slow, hot day trolling for photos, when a dazed-looking waiter walks by carrying a transistor radio. Excited Creole chatter and static rattles out of the speaker. “Baby Doc just landed,” the waiter says to no one in particular. Wait. After 25 years, Haiti’s murderous ex-president is here? Or is this just another rumor? Just in case, I run upstairs, get Mac, call our driver, and try to figure out what the hell is going on. Is Baby Doc really here in Port-au-Prince? Has he left the airport? Will people riot? Shit.

Supporters wait for a glimpse of Jean-Claude Duvalier at the Port-au-Prince airport.

Supporters wait for a glimpse of Jean-Claude Duvalier at the Port-au-Prince airport.

The streets of Port-au-Prince are completely choked with traffic: cars, motorbikes, buses, people. Fortunately Sam, our driver, is a former AP photographer who knows how to hustle his way through. We arrive at the airport; it’s dark, chaotic. Is he still here? By now, we know he’s definitely back in the country.

UN and Haitian police blocking a gate at the airport

UN and Haitian police blocking a gate at the airport

A local kid tells us he knows where Baby Doc’s motorcade is. We follow him to a gate blocked by UN and Haitian police. Nearby, a crowd is chanting, cheering, yelling. I can see journalists on the other side of the gate, but the police won’t budge. They point back the way we came and say there’s a gate 100 meters away where we can enter. We run back, 100 meters and then some. Then we finally say “fuck it” and climb the tall, spiked fence; I rip my jeans and cut my hand in the process. We run back toward the UN soldiers only to find ourselves in front of another locked gate. A guy in the crowd suggest I just climb over it like the other journalists did. I’m out of shape and I have three cameras dangling around my neck; this could go badly. I climb to the top of a brick pillar and drop 10 feet down, landing with a dull thud. A few people in the crowd cheer. They probably thought I was gonna eat it. I know I did.

Suddenly, UN police open the gate. It was a decoy! We run to where we think the motorcade is actually going to pass. Sam pushes me to the front of a tightly packed crowd of supporters, journalists, and police. And then—Duvalier’s motorcade passes. Wham. Wham. Wham. I fire off a handful of shots. He’s smiling, waving out of the window of an SUV. Did I get the shot?

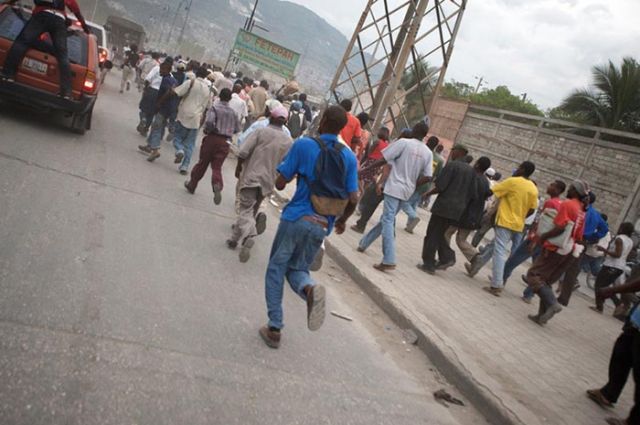

Baby Doc’s motorcade makes its way past us, followed by cops on motorbikes, ATVs, trucks. The throngs run behind his entourage. Mac and I get back in Sam’s car and drive around searching for the motorcade, protests, or celebrations. Sam calls his leads to find out where Baby Doc went. After not turning up anything, we go back to the hotel. I file photos and sleep.

Supporters chase Duvalier’s motorcade.

Supporters chase Duvalier’s motorcade.

Monday morning. Duvalier is now holed up at a luxury hotel in Petionville called the Karibe. We’ve heard rumors of a press conference at 9 a.m., 10 a.m., or 12 p.m., but no one knows anything for sure, so we go to the Karibe for stakeout duty and wait. Nine o’clock passes, then 10, then 12. Nothing. Finally, a man in a suit arrives at the hotel and goes up to Baby Doc’s room. The man turns out to be Haiti’s former ambassador to France, Henry Robert Sterlin, who then comes out and tells the media swarm that the press conference has been postponed. Tomorrow, there will be a press conference to announce when Duvalier’s press conference will take place. Great.

Henry Robert Sterlin and the press

Henry Robert Sterlin and the press

Tuesday morning. During breakfast in our hotel restaurant, a number of journalists jump up and head out. Word comes that Duvalier is going to be arrested. Shit! Mac and I call a taxi; it seems cheaper and faster than having our driver come get us and take us to where Baby Doc is staying. But the cab shows up late and the driver is slow. His old station wagon rattles, huffs, and puffs at it climbs to Petionville. More than once I almost jump out and start running; I’m sure we’ll get to the Karibe long after the police have whisked Baby Doc away.

The media swarm at the Karibe Hotel

The media swarm at the Karibe Hotel Duvalier’s lawyer, Gervais Charles, talks to reporters outside the hotel. A lot of pushing to get a really simple shot. But when we get to the Karibe, Baby Doc’s still there—along with a huge contingent of police and media. We wait. Anyone who enters or leaves the hotel is mobbed. The chief of police. Duvalier’s lawyer. I stay close to the armored personnel carrier the Haitians have backed up to the hotel door and plant myself between Jonathan Torgovnik (who shot Mac’s recent Haiti piece) and one of my personal photographer heroes, Stanley Greene.

Duvalier’s lawyer, Gervais Charles, talks to reporters outside the hotel. A lot of pushing to get a really simple shot. But when we get to the Karibe, Baby Doc’s still there—along with a huge contingent of police and media. We wait. Anyone who enters or leaves the hotel is mobbed. The chief of police. Duvalier’s lawyer. I stay close to the armored personnel carrier the Haitians have backed up to the hotel door and plant myself between Jonathan Torgovnik (who shot Mac’s recent Haiti piece) and one of my personal photographer heroes, Stanley Greene.

Haitian police wait by the armored car that was supposedly taking Duvalier to the courthouse.

Haitian police wait by the armored car that was supposedly taking Duvalier to the courthouse. UN police push back against the crush of journalists.

UN police push back against the crush of journalists.

Suddenly, Duvalier starts making his way down the hotel stairs, stopping at each landing to wave. Journalists push in closer; UN and Haitian police push back. As Baby Doc approaches the ground floor, the crowd becomes a bruising, jostling, shoving herd. A TV camera smashes my watch. A photographer next to me gets knocked down. UN cops come in and start clearing a path with batons and clear plastic shields and then…wait, where’d he go? The police close the armored personnel carrier’s doors, empty. Shit, another decoy? I haul ass with the other photographers toward what I assume is the hotel’s back door, jumping off a generator over a bush, my three cameras slapping into each other. At this point I’m just part of the herd; I have no real idea where I was going. There’s nothing at the other entrance. He got away…but how? Where?

Duvalier supporters gather near the Karibe Hotel.

Duvalier supporters gather near the Karibe Hotel.

A group of supporters has gathered at the bottom of the hill from the hotel; I go down to photograph them. If I can’t get Baby Doc, I’ll at least get “reaction.” I shoot his supporters, people holding signs and chanting. Right when things are calming down, Baby Doc’s motorcade snakes its way down the hill towards downtown.

Duvalier’s motorcade

Duvalier’s motorcade Duvalier’s police escort clears the crowd.

Duvalier’s police escort clears the crowd.

I keep up on foot as long as I can, jostling with police and other photographers for decent shots of the motorcade. At one point the motorcade stops; the driver’s door of Baby Doc’s car opens. That doesn’t make sense. One of the rear windows gets cracked. The driver’s door closes again, but not before Duvalier sticks his hand out to wave to his supporters.

About a mile or so from the hotel, Duvalier’s car and the whole motorcade pull away, out of sight. I’m exhausted and unsure what else to do, so I start walking. I have no real idea where I’m going, and no money on me for any of the taxis that pull up to offer me a ride, but I keep walking. That’s when a random guy pulls up on a yellow motorbike.

He asks if I want to find the motorcade. I tell him yes and get on the back of his bike. We speed away. His name is François. My savior.

Baby Doc being led into the courthouse in Port-au-Prince.

Baby Doc being led into the courthouse in Port-au-Prince. Baby Doc supporters after he is taken into the courthouse

Baby Doc supporters after he is taken into the courthouse Haitian police with US SWAT members—and lots and lots of guns

Haitian police with US SWAT members—and lots and lots of guns

François weaves in and out of traffic and drops me off at the Port-au-Prince courthouse. I arrive just as Baby Doc is being led into court. There’s more jostling, pushing. I get a shot of the dictator as he’s getting out of his car. The police close the doors on the courthouse and, man, there are a lot of guns here. Some US SWAT guys give me some much-needed water. I call Mac to find out where she is. We lost contact as soon as I took off from the Karibe. I go out to shoot some of the crowds gathered in front of the courthouse.

Duvalier supporters wait outside the courthouse

Duvalier supporters wait outside the courthouse Duvalier supporters do a dance.

Duvalier supporters do a dance.

Since I didn’t really come to Haiti to file breaking news, I don’t have the equipment to file from the field, so I head back to the hotel to send pictures to Mother Jones HQ.

At the hotel, I down a Prestige beer and file photos. The rest of the day should be easier. Just then another photographer tells me that Duvalier is going to be taken back to his hotel at any minute. We jump on the back of her motorbike—three of us, including the motorbike driver—and head back to the courthouse.

Young Duvalier supportersBack at the courthous, the gates are closed, sealed with a heavy metal gate. No one’s getting in or out, so I mill around outside. No one’s quite sure what’s going to happen. Will the celebrations turn violent? Things could turn at any moment. Two tires were burned while I was at the hotel filing photos. The requisite burning-tire photo—I missed it. No loss.

Young Duvalier supportersBack at the courthous, the gates are closed, sealed with a heavy metal gate. No one’s getting in or out, so I mill around outside. No one’s quite sure what’s going to happen. Will the celebrations turn violent? Things could turn at any moment. Two tires were burned while I was at the hotel filing photos. The requisite burning-tire photo—I missed it. No loss.

Storming the courthouse gates…

Storming the courthouse gates… …and the police response

…and the police response

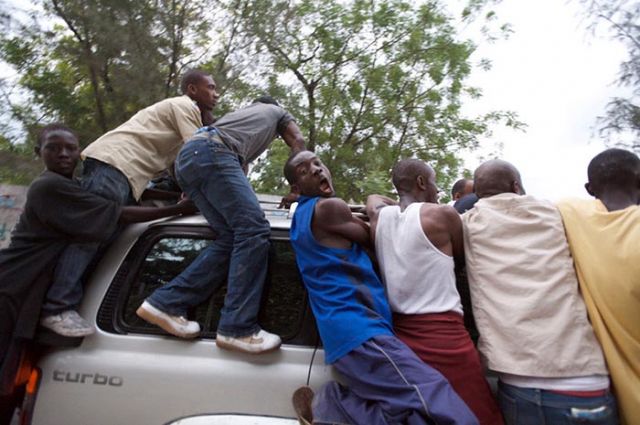

A little before 5 p.m., Duvalier’s motorcade finally emerges. I grab some shots of its departure, then jump on the back of François’ motorbike. He stays right next to Duvalier’s car, dodging other motorbikes, piles of rubble and trash, military vehicles, pigs, and pedestrians. Crowds of people cheer as Duvalier passes.

Duvalier’s motorcade leaves the courthouse. The chase is on again.

Duvalier’s motorcade leaves the courthouse. The chase is on again. Chasing Baby Doc’s motorcade

Chasing Baby Doc’s motorcade Supporters catch a lift to follow Duvalier.

Supporters catch a lift to follow Duvalier. Haitians cheering along the motorcade route

Haitians cheering along the motorcade route

It’s getting dark. Back at Baby Doc’s hotel, I scramble off the motorbike, run up the driveaway, and fall, landing on my elbow and one of my cameras and ohfuckithurts. I bend my arm to make sure it’s not broken. I get up, and run to Duvalier’s car. That spill cost me a great spot.

The media surround Duvalier at his hotel.Baby Doc enters his hotel. Inexplicably, security allows photojournalists to trail him inside. Duvalier looks totally dazed. He’s surrounded on all sides by TV and still cameras and reporters with recorders. He’s being led into a small, empty banquet room. I see where he’s headed, enter through another door, and perch myself against a wall. Finally, the photo hunt is over. I’m in a perfect position to shoot the dictator. And I fire off some shots right before he’s whisked through a door that closes and locks.

The media surround Duvalier at his hotel.Baby Doc enters his hotel. Inexplicably, security allows photojournalists to trail him inside. Duvalier looks totally dazed. He’s surrounded on all sides by TV and still cameras and reporters with recorders. He’s being led into a small, empty banquet room. I see where he’s headed, enter through another door, and perch myself against a wall. Finally, the photo hunt is over. I’m in a perfect position to shoot the dictator. And I fire off some shots right before he’s whisked through a door that closes and locks.

Duvalier and his companion, Veronique RoyI head back to the hotel to download, edit, caption and file. After fourteen hours, my day is done. I shot the dictator.

Duvalier and his companion, Veronique RoyI head back to the hotel to download, edit, caption and file. After fourteen hours, my day is done. I shot the dictator.