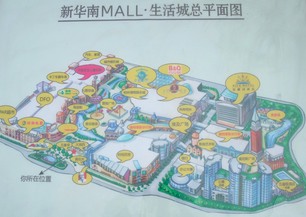

<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SouthChinaMall_map.JPG">South China Mall Artist's Rendering: Swoolverton/Wikimedia Commons</a>

THE CHINESE BORDER OUTPOST of Erenhot is part boomtown, part ghost town. Residents are seldom seen in much of this Gobi Desert location, where little that’s green grows on its own. Strips of trees that workers have planted along the roads are buttressed with plywood or have toppled over, their roots blown free of dirt.

But there’s activity aplenty on the town’s construction sites. Over the past decade, scores of empty strip malls and apartment buildings have sprouted from the sand—an eerie skyline visible for miles across the flatlands. At dusk, construction workers headed home on bikes and mopeds are sometimes just about the only traffic on the wide, freshly paved streets, illuminated by shiny new lampposts.

In recent years, economists have raved about China’s double-digit growth—which dropped to a still-impressive 9 percent in 2008 and 2009, even as much of the world slouched through the recession. But this turbocharged expansion is less about the invisible hand than the iron fist: the enormous engine of the state geared to drive GDP at the expense of everything else.

China’s obsession with economic metrics hearkens back to the Mao days, when industrial production stats took center stage. Nowadays, careers of Chinese bureaucrats hinge on two things—growth and lack of social unrest—that are often in conflict. Pollution has been a major cause of dissent, and China’s poor are struggling with rising costs, especially in health care and education. Literacy rates took a dip recently, and some data (pdf) suggest that incomes of the poorest citizens have lagged compared with the rest of the nation.

Despite this, the country has entombed its new wealth in concrete and steel. You can see it in Dongguan, in Guangdong province, where the world’s largest mall stands empty, save for a few hamburger chains. And in Beijing’s tallest building, a year old and still unopened. It is evident in six-lane boulevards where most of the traffic is bicycle carts. And in cities like Erenhot, where the relentless construction continues, oblivious to a dearth of demand.

There is a certain desolate beauty in the barren, windswept desert steppe that surrounds Erenhot. But the empty strip malls with their storefronts all bearing the same surreal sign—”Careful!”—and the uninhabited buildings looming gray and solitary make the place feel as alien as a video-game backdrop. Over tofu soup, I commiserate with a restaurateur who can’t explain exactly what possessed her and her husband to come here a year ago, leaving the kids with their grandparents in Sichuan. Propping her head listlessly on one elbow, she can barely hide the melancholy of having sunk the family savings into an eatery surrounded by vacant storefronts. As for the construction spree, she, too, is at a loss. “Corruption,” she shrugs.

A better explanation, perhaps, stands not far from the restaurant—a sculpture of shiny arrows swirling around vertical bars, projecting up into the desert sky. It is a recent genre of public art that can be seen all across China: a state-commissioned depiction of progress and prosperity.