THE RUMORS ABOUT MARGARITA CRISPIN started soon after her first day as a customs officer in El Paso, Texas. In March 2003, Crispin started working the line at the Paso Del Norte bridge, across from Ciudad Juárez. Nearly one-fifth of all drugs seized coming across the border enter through the El Paso-Juárez area, and the region is viciously contested by Mexican cartels. So when Crispin waved off the dogs that sniff out drugs in the long line of cars waiting to enter the United States, saying she didn’t like them around her, it raised a few eyebrcows.

Corruption among border agents is nothing new. But what makes Crispin’s case different is that investigators from the Department of Homeland Security suspect she’d been recruited by a friend with ties to the Juárez cartel before she took the job. Almost immediately after completing her training and putting on her badge, she began to help traffickers “cross loads.” As many as three vans stuffed with drugs would pass through her inspection lane several times a week. By the time she was arrested in July 2007, Crispin is thought to have let more than 2,200 pounds of marijuana into the United States. In return, DHS agents say, she received millions in bribes, much of which remains unaccounted for. Last April, she pled guilty and was sentenced to 20 years and ordered to forfeit as much as $5 million, plus jewelry and a truck.

At least two other recently arrested agents are suspected of being drug cartel plants. And as Customs and Border Protection continues its biggest hiring surge ever, investigators see infiltration as a growing threat. By this fall, CBP expects to have more than 20,000 agents, twice what it had in 2001. “We’re seeing fewer reports by agents of being approached by traffickers,” says James Smith, special agent in charge of the DHS inspector general’s El Paso office, which investigates corruption and misconduct cases. “We’re not just seeing disgruntled employees going bad. We’re seeing more cases where agents are already employed by the drug-trafficking and alien-smuggling organizations before they go to work for CBP.”

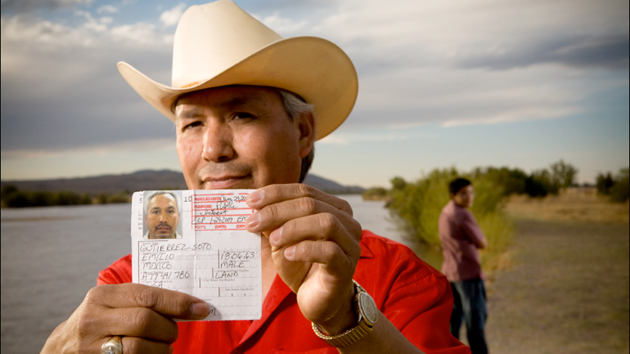

Speaking Spanish is a required skill for agents, and many have family and other ties to Mexico. Though agents are subjected to extensive background checks, it is a challenge to indentify red flags in applicants’ personal histories or connections across the border. Since the agency began giving polygraph tests to potential hires last year, investigators have found four applicants planted by the cartels. Still, they’re concerned that others may have already slipped through.

Some officials worry that the screening program may not be able to keep up with the pace of recruitment. But James Tomsheck, CBP’s assistant commissioner for internal affairs, says the agency hasn’t cut corners. Rather, he thinks the increased risk of cartels’ penetrating its ranks is an unintended consequence of the successful efforts to secure the border with fencing and more agents. “The threat, as it emanates from the cartels, is a real one,” he says. “Our concern is, what is it that we don’t know? Who is in our workforce that we have not yet detected?”