Introduction by Tom Engelhardt

Recently, in a Washington Post op-ed, Mark Danner wrote: “However much we would like the [torture] scandal to be confined to the story of what was done in those isolated rooms on the other side of the world where interrogators plied their arts, and in the air-conditioned government offices where officials devised ‘legal’ rationales, the story includes a second narrative that tells of a society that knew about these things and chose to do nothing.” Danner, who did as much as anyone to help uncover what the Bush administration was up to in its secret prisons abroad, should know.

According to the latest Gallup Poll, a bare majority (51%) of Americans now favor some kind of major investigation “into the use of harsh interrogation techniques on terrorism suspects during the Bush administration.” On the other hand, 55% “still believe in retrospect that the use of the interrogation techniques was justified.” Of course, who knows what those percentages might have been if Gallup’s pollsters, in their questions, had used the word “torture,” rather than—like most of the mainstream—skittering away from it in favor of a variation on the chosen phrase of the Bush administration, “enhanced interrogation techniques.”

While Americans remain deeply divided on the use of, investigation of, and prosecution of Bush-era torture practices, at least the subject has now burst into the center of political discussion and debate. In the wake of the Obama administration’s release of yet more documents from a seemingly bottomless archive of Justice Department “torture memos,” writing on the subject has been fiery, argumentative, provocative, despairing, or some combination of the above. More important, though, it’s been pouring out in all its variety to remind us that what was done in our name can still be repudiated in a variety of ways.

Just a few suggestions, if you want to plunge in. You might start with international human rights lawyer Scott Horton’s No Comment blog at Harper’s Magazine on-line. The guy’s been all over the subject for a long, long time and his material is unimpeachably on target (and smart). Glenn Greenwald’s Unclaimed Territory column at Salon.com is also always worth a careful look, as is Nieman Watchdog, a site I value that has often focused on both torture and press coverage of it. (The site is run by Dan Froomkin, whose Washington Post column, White House Watch, is a daily must-read.)

At his AfterDowningStreet website, David Swanson has been writing passionately and brilliantly about why a special prosecutor should be appointed and Bush officials, right up to the former president, should be charged with crimes, while over at Truthout, Elizabeth de la Vega, has offered a provocative discussion of why a special prosecutor should not (yet) be appointed. (Both, by the way, have been TomDispatch regulars.) And don’t forget Mark Karlin, who edits Buzzflash.com, and has been penning powerful pieces lately on why Bush and Cheney (et al.) should someday be brought up on actual murder charges. And that’s just to scratch the surface of this explosive subject.

And then there’s Karen Greenberg, TomDispatch regular, Executive Director of the Center on Law and Security at the NYU School of Law, and author most recently of The Least Worst Place: Guantanamo’s First 100 Days. In a piece that is part analytic, part confessional, and totally original, she frames the torture debate in a larger way, in terms of the death of the human rights movement. (To catch an audio interview in which she discusses those “torture memos,” click here.) Tom

Kiss the Era of Human Rights Goodbye

What Bush Willed to Obama and the World

By Karen J. Greenberg

These days, it’s virtually impossible to escape the world of torture the Bush administration constructed. Whether we like it or not, almost every day we learn ever more about the full range of its shameful policies, about who the culprits were, and just which crimes they might be prosecuted for. But in the morass of memos, testimony, op-eds, punditry, whistle-blowing, documents, and who knows what else, with all the blaming, evasion, and denial going on, somehow we’ve overlooked the most significant victim of all. One casualty of the Bush torture policies—certainly, at least equal in damage to those who were tortured and the country whose laws were twisted and perverted in the process—has been human rights itself. And no one even seems to notice.

So let’s be utterly clear: The policies of the Bush administration were not just horrific in themselves or to others, they may also have brought to an end the human rights movement as we know it.

One need only glance at the recently released Justice Department memos, which have caused such a media storm of late, for the story of what has happened to human rights in American hands to become clearer. It is not just, as New York Times columnist Frank Rich recently wrote, that “our government methodically authorized torture and lied about it.” No less important, though hardly commented upon, is this fact: the United States succumbed to the exact patterns of abusive state action that the human rights movement was created to outlaw forever. What the Bush administration pursued, after all, was a policy of state-sponsored, legally codified dehumanization designed to torture (and in some cases destroy) individuals, which was to be systematically and bureaucratically implemented in the name of the greater good of the country, however defined.

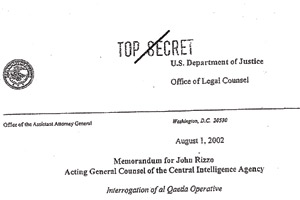

The documents that the Obama administration and Congress have just released make this conclusion impossible to avoid. These include four memos written by the Office of Legal Council between 2002 and 2005, the Senate Armed Services Committee Report on Interrogation Practices, and the Senate Select Committee Narrative on the Chronology of the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) Memos. Added to this must be the publication by Mark Danner in the New York Review of Books of a previously secret International Committee of the Red Cross report on abuse at Guantanamo Bay.

As a group, these documents reveal that the pattern of systematic abuse at the hands of the American government during George W. Bush’s Global War on Terror has been a textbook case of human rights violations designed and implemented at the highest levels of government. First, there was the assault on the English language, a necessary initial step in the process of changing the national mindset of a country about to become a first-class human-rights abuser. As Susan Sontag once wrote in a piece about the Bush administration and its pretzeling of language, “Words alter, words add, words subtract.”

Creating American-style Torture Techniques and Manuals

Just as the U.S. military at Guantanamo was instructed in January 2002 never to refer to that detention facility as a “prison” and never to call the inmates “prisoners,” so the infamous OLC August 1, 2002 “torture memo” that came out of the Justice Department, and was made public in 2004, officially banished torture to the dust heap of history when it came to American actions. It was now to be considered only physical pain of “an intensity akin to that which accompanies serious physical injury such as death or organ failure,” or mental pain which produced “lasting psychological harm.”

Now, that memo’s twin has just been released, providing more detailed reasoning about the redefinition of torture. This second August 1, 2002 memo gives us an even more comprehensive picture of the rationale behind the insistence of the Justice Department that the techniques being applied to detainees in the War on Terror in no way amounted to torture.

Examining specific techniques of coercive interrogation, all of which would technically violate the U.S. Anti-Torture Statute [18 U.S.C. §§ 2340-2340A], Justice Department officials craftily reasoned their way out of old, well-accepted definitions of universally agreed-upon acts of torture. Thanks to creatively worded explanations, this new August 1, 2002 memo declared that neither “the waterboard,” “walling,” nor being placed in a box amounted to torture. In situation after grim situation, torture, it was explained, just wasn’t the right word.

The focus of the just released memo was the interrogation of al-Qaeda terror suspect Abu Zubaydah. According to the memo, Zubaydah simply wouldn’t feel pain or suffer repercussions as others might have from these redefined acts of torture. Similarly, extreme “stress positions” could be used on him because he “appears to be quite flexible despite his wound,” and because he had already proven he could withstand other abuses. “You have orally informed us that you… have previously kept him awake for 72 hours. From which no mental or physical harm resulted.” The Justice Department lawyers, informed by the CIA that Zubaydah was in exceptional physical and psychological condition, conveniently reasoned that the techniques in question wouldn’t harm him—and, of course, they would be oh-so-helpful to the longer term torture goals of the Bush administration.

The focus of the just released memo was the interrogation of al-Qaeda terror suspect Abu Zubaydah. According to the memo, Zubaydah simply wouldn’t feel pain or suffer repercussions as others might have from these redefined acts of torture. Similarly, extreme “stress positions” could be used on him because he “appears to be quite flexible despite his wound,” and because he had already proven he could withstand other abuses. “You have orally informed us that you… have previously kept him awake for 72 hours. From which no mental or physical harm resulted.” The Justice Department lawyers, informed by the CIA that Zubaydah was in exceptional physical and psychological condition, conveniently reasoned that the techniques in question wouldn’t harm him—and, of course, they would be oh-so-helpful to the longer term torture goals of the Bush administration.

The next step from offering reasons for redefining torture for just one individual—Zubaydah—to a general policy proved easy, despite the fact that Zubaydah’s powers to withstand and recuperate from these techniques were deemed exceptional. The memos assumed that the next detainees to undergo these methods of interrogation were somehow in the same category as the Navy Seals who had experienced them while undergoing training to resist the techniques of torturers from totalitarian or rogue regimes. Repeatedly, that August memo insisted that such techniques, rather than being the property of torturing regimes, really added up to little more than “physical discomfort,” to (at worst) only temporary psychological disorientation, rather than a “profound” disruption of one’s psyche. “No prolonged mental harm,” the memo asserted, “would result from the use of these proposed procedures.”

One by one, then, the techniques were intricately described in ways that repainted them the color of mere “abuse,” which sounds so penny ante, rather than torture. When it came to sleep deprivation, for example, the reasoning was that, even if “abnormal reactions” did result, “reactions abate after the individual is permitted to sleep.” Likewise, “the goal of the facial slap is not to inflict physical pain that is severe or lasting. Instead the purpose of the facial slap is to induce shock, surprise, and/or humiliation.”

The subjects might believe themselves tortured, but they would be wrong. “The idea,” as the memo wrote about what’s now called “walling,” “is to create a sound that will make the impact seem far worse than it is and that will be far worse than any injury that might result… [whereby] the interrogator pulls the individual forward and then quickly and firmly pushes the individual into the wall. It is the individual’s shoulder blades that hit the wall,” but his “head and neck are supported by a rolled towel… to help prevent whiplash.”

Even when there is a modest admission that some damage could actually occur—that, for instance, “placement” in “small,” “cramped” confinement boxes could “disrupt profoundly the senses”—it was quickly dismissed on the grounds that such confinement wasn’t to extend beyond two hours. And finally, there were those assurances in the matter of waterboarding, or so-called simulated drowning, that “the sensation of drowning is immediately relieved” once the procedure is stopped.

And this, of course, just grazes the surface of these nightmarish documents that should bring to mind the demonic regimes that gave rise to the human rights movement. Among other things, the Justice Department lawyers writing them weren’t just changing the language and redefining torture out of existence, they were offering nothing short of a detailed manual for those about to go to work on actual human beings in just how to perform torture. Take for instance, this description of how to waterboard correctly:

“…[T]he individual is bound securely to an inclined bench, which is approximately four feet by seven feet. The individual’s feet are generally elevated. A cloth is placed over the forehead and eyes. Water is then applied to the cloth in a controlled manner. As this is done, the cloth is lowered until it covers both the nose and mouth. Once the cloth is saturated and completely covers the mouth and nose, air flow is slightly restricted for 20 to 40 seconds…This causes an increase in carbon dioxide level in the individual’s blood… [stimulating] increased effort to breathe… [producing] the perception of ‘suffocation and incipient panic,’ i.e. the perception of drowning…”

One day, perhaps soon, much of the rest of the minutiae produced by the Bush administration’s torture-policy bureaucracy will come to light. Procurement lists, for example, will undoubtedly be found. After all, who ordered the sandbags for use as hoods, the collars with chains for bashing detainees’ heads into walls, the chemical lights for sodomy and flesh burns, or the women’s underwear? The training manuals, whatever they were called, will be discovered: the schooling of dogs to bite on command, the precise use of the waterboard to get the best effects, the experiments in spreading the fingers just wide enough in a slap to comport with policy. The Senate Armed Services Committee’s report, released last week, has already begun to identify the existence of training sessions in techniques redefined as not rising to the level of torture.

For now, however, we have far more than we need to know that what the United States started when, in 1948, it led the effort to create the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and became the moral figurehead for human rights concerns worldwide for more than a half-century, has come to an end. Eleanor Roosevelt, who led the commission that drafted that 1948 Declaration, remarked at the time that the United States was “the showcase” for the principles embodied in the declaration. Sixty-one years later, that is no longer true.

The Human Rights Movement Is History

From the very beginning of my own descent into the world of Bush administration torture policy—and, among other things, I was the co-editor of a 2005 collection of documents, already leaking out then, called The Torture Papers—I have resisted associating what U.S. officials were doing with past state atrocities. That was another, far worse realm, I reasoned, one in which countless people were disappeared and millions murdered. After all, the unfolding torture policy didn’t kill (though some detainees certainly did die from maltreatment in U.S. secret and not-so-secret prisons abroad), it only inflicted pain. Others pointed out similarities between such Bush administration outrages and past barbarisms, but I veered away from analogies which, to my mind, undermined the evils of this particular story. So when Scott Horton compared the Nazi commandant of Auschwitz Rudolf Hoess to those who crafted the U.S. torture policy or Susan Sontag compared administration abuses of language to the linguistic perversions that preceded genocidal acts against the Hutus in Rwanda, I recoiled.

Analogies of such an extreme order just didn’t suit me. But what I’ve resisted for five years, since the first Abu Ghraib revelations in the spring of 2004, I now find sadly indisputable. The supposed moral exceptionalism of the most powerful nation on Earth is no more. In its action-packed eight years, the Bush administration ensured that the United States would be the most ordinary of abusing, torturing nations.

Through perverse language, a twisting of the law, and an immersion in the precise details of implementing torture techniques, the United States renounced its position as the leader of the global human rights movement. Abandoned by the country it long considered its greatest ally, that movement now teeters at the edge of its grave. That’s what the torture memos and the present media uproar over torture really mean.

Karen J. Greenberg is the Executive Director of the Center on Law and Security at the NYU School of Law, the co-editor of The Torture Papers: The Road to Abu Ghraib and the editor of The Torture Debate in America. Her most recent book is The Least Worst Place: Guantanamo’s First 100 Days. To catch an audio interview in which she discusses the Bush administration “torture memos,” click here.