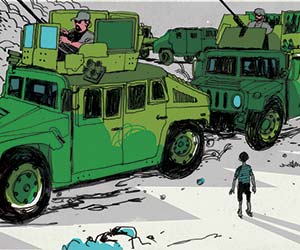

Illustration: Josh Cochran

“You give me money, I don’t care who you are.” It was late October, and Zimbabwe’s defense attaché, a soft-spoken, thick-shouldered lieutenant colonel, was explaining his country’s freewheeling approach to business in the banquet room of the Liaison hotel on Capitol Hill. Mingling around him were representatives from some of the world’s best-known private security and military contracting firms, gathered to explore their prospects in the industry’s next frontier: Africa. None betrayed any eagerness to do business with Robert Mugabe, notwithstanding assurances from the beaming attaché that Zimbabwe—”the second-largest economy in southern Africa”—remains strong despite 231 million percent annual inflation. But there were plenty of other avenues to explore, including a recent shake-up in the US military’s command structure that seemed to promise new demand for firms like Blackwater (which recently changed its name to Xe), Triple Canopy, and DynCorp.

The guests, dressed in business attire and the odd military uniform, were gathered for the annual summit of the International Peace Operations Association (IPOA), a trade group. Industry reps had traveled from as far as Dubai and Malta to discuss this year’s topic—the Pentagon’s newly established US Africa Command, or AFRICOM—and to browse booths hawking everything from armored vehicles to high-risk insurance. Arrayed on a table in the back were piles of corporate literature, complete with pictures of Third World children and Western contractors delivering aid, a popular industry meme. Among the big-ticket attractions was a keynote address from William E. “Kip” Ward, the four-star general in charge of AFRICOM.

The event drew record attendance, and industry veterans were not surprised. “Everybody’s always been interested in Africa,” Chris Taylor, a former Blackwater executive and now a vice president at Ohio-based Mission Essential Personnel, explained over drinks in the hotel bar. “It represents a huge opportunity for business.”

Africa is no stranger to armed security contractors; the industry in its modern incarnation was born when mercenary firms like Executive Outcomes and Sandline International fought for embattled African governments during the 1990s, allegedly in exchange for diamond and oil concessions. Since then, security contractors have gained broader acceptance. But serious concerns remain about the role they might play in their old stomping grounds.

“There is a crying, desperate need for some of the services that these people provide,” said Alex Yearsley, the head of special projects at Global Witness, a London-based human rights group. “There’s no question they can do it. It’s a question of when you’re going to have a questionable regime hiring these people to kick out indigenous communities or [gain access to] mining areas. That’s when it gets problematic.”

To companies seeking entrée to the continent, the military’s new Africa command could provide a key foothold. To pursue its mission of security, diplomacy, and development, AFRICOM‘s outreach and partnership director, Paul Saxton, told a packed audience at the conference, the command plans to enlist the help of the private sector. “We’re reaching out.”

Reliance on contractors, though, could add to the controversy already engulfing AFRICOM, especially the fears that the military’s forays into development work could blur the line between aid workers and soldiers or hired guns. Taylor, the former Blackwater executive, downplayed such concerns. AFRICOM, he says, will likely train “partner nations” to provide a secure environment for humanitarian projects. “It doesn’t mean that a bunch of dudes with guns are going to show up with bags of rice.”

Perhaps not, but critics have also accused the Pentagon of using africom as a fig leaf for broader geopolitical objectives; they view the command as little more than a strategic maneuver to counter China’s pursuit of Africa’s natural resources. “I want to see it succeed,” said the security director of a well-known NGO who is nonetheless wary of AFRICOM’s mission. “I want to see development that is focused on empowerment, not as some tactic for US interests. That’s not development. That’s manipulation.”

Africans, too, have greeted the Pentagon’s plans with suspicion. As US officials toured the continent in search of a location for the new command’s headquarters, they met with so much opposition that they eventually decided to operate from Germany for the time being. This frosty reception should have come as no surprise, Eeben Barlow, the former South African soldier who founded Executive Outcomes, commented on his blog in November. “Looking at…US administrations’ record in Africa, it is one long script of betrayal, destabilisation, political blackmail and even worse.” African nations, he noted, “remain extremely reluctant and wary to allow the wolf to guard their sheep.”

But AFRICOM‘s start-up problems have not dampened the enthusiasm of Barlow’s cohorts in the security industry. They also see opportunities in other federal initiatives—such as a massive, and little-known, State Department contract, the Africa Peacekeeping Program. Worth some $1 billion over five years, it covers work in countries including Somalia, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, everything from logistics support and construction to training and advising African troops, flying aerial surveillance missions, and improving coastal security. Triple Canopy and Blackwater are said to be among those that submitted proposals.

At the IPOA conference, we spoke with two Blackwater representatives, who during that morning’s panel discussion had taken seats beside AFRICOM‘s Paul Saxton. With Somali pirates’ seizure of a Ukrainian ship carrying 33 battle tanks fresh in the news, they told us, the company saw opportunity in the area of “maritime security.” In mid-October, Blackwater had announced that its 183-foot, helipad-equipped ship, the McArthur, was standing by to assist shipping companies in the area. (After being contacted by at least 70 shipping and insurance firms interested in its anti-piracy services, Blackwater in December held three days of meetings in London with prospective clients.) But the core of Blackwater’s ambition in Africa is to transition away from the high-profile “personal protection” work that has brought it so much opprobrium in Iraq and Afghanistan; to that end, its representatives told us, it has opened an office in Nairobi, Kenya, the better to go after opportunities to train African military and security forces.

If the sheer number of companies represented at the ipoa conference is any indication, Blackwater’s envoys will run into plenty of their competitors—and that makes some observers uneasy. “You start bringing these people on the scene, they come in as trainers, but at the drop of a hat they can be other things,” said the ngo security director. “They have skills, they have something to bring, but it’s a double-edged sword, and it depends on which edge is being presented.”