Is anyone still “hunting down” Osama? Should the military allow photos of coffins coming home? When soldiers have worse odds of getting killed in Afghanistan than in Iraq, why do we hardly hear about them? No to the first; yes to the second; and as to the third, Rick Scavetta explains the Pentagon’s systematic approach to masking fatalities.

Since age 18, Scavetta has served off and on in the military. He reported for Stars and Stripes, the official newspaper of the U.S. Armed Forces, for three years in dozens of countries from Bosnia to Afghanistan. Then he was the army’s chief of media relations in Afghanistan for a year, ending in February 2006. He embedded reporters from more than 200 news agencies, from Tom Brokaw to local Afghan reporters. For all his attempts to bring the war to the public, he says, “America as a whole goes on shopping.”

Mother Jones: Were you the Pentagon’s main public relations person in Afghanistan?

Rick Scavetta: No, that was someone else who sat in an office and gave press conferences in Kabul. I was the guide. When they show up and say, “How the hell do I get out to where the marines are on some mountaintop,” I was the one that brought them into the base, gave them initial briefings, situation awareness, coordinated all their movements, escorted them out there, linked them up with the unit, and if it was TV or something cumbersome, stayed there to make sure everything went smoothly.

MJ: Did you ever have to restrict anyone’s access to troops?

RS: There were a couple times. We had an incident where some U.S. forces were caught on video disposing Taliban remains by burning them, for hygienic reasons — they were rotting on the hillside next to them. At the time, the local brigade commander in Kandahar said, “No more reporters.” I went all the way up to two-star generals to get these guys on the ground. The Australian news media tried to play it as, “These guys are desecrating Islamic values.” The sad fact was, some psych operation officers got a hold of this and created a broadcast message to the enemy hiding out in a village nearby, to taunt them into coming out. Even the guy who shot it said this wasn’t a desecration or anti-Islam. It was a mess for the army. The local commander said, “Until we sort this out and do our investigation, I’m not taking any more reporters.” There’s still a butt-stroke mentality among military officers.

MJ: What’s a butt-stroke mentality?

RS: The butt of your rifle — if you crack that into someone’s face it’s called a butt-stroke. It’s this: “I don’t need the press, and I hate the press, and why am I dealing with the press?” There’s always been this love/hate relationship between the military and the press, and there are still some people who just don’t get that today with 24-hour news networks and the Internet, not only our public but the other society is craving info on a battlefield.

MJ: How did you help reporters get stories?

RS: Ron Allen from NBC news — I knew of an upcoming operation that was going to be a heavy combat operation. There was going to be action. I told a producer, “I can’t talk to you about future operations. But I can tell you, if you send a news crew three weeks from today, I guarantee I can get you bullets flying.” They flew from New York to Dubai to Kabul. I had a Black Hawk helicopter waiting and flew them about an hour away, got in a Chinook helicopter and went to Tora Bora, the mountains where we last saw Bin Laden. The marines were launching an offensive operation. He said, “Eighteen hours ago I was in New York.” But the reporters hit the ground running and were keeping up with marines in 9,000-foot mountains. We all got full packs and are expecting enemy combat. Pretty amazing if you think about it.

MJ: Sounds pretty intense—

RS: You gotta hear the end of it. They don’t get to see the combat. They don’t find the enemy. We end up dropping off a lot of humanitarian supplies. Ron looked at me and said, “Jeez, Rick, we don’t have the combat footage that you talked about.” I said to Ron, “Why don’t you out with another company, just north of us in a place called Mehtar Lam in the Alising River Valley?” We go out there and we got hit by an IED [improvised explosive device], and they got their combat footage. We spent the next three days clearing out the villages around where our convoy we got hit. And for all this, two weeks in the field, this insanity, thousands of dollars, risking our lives? We got 120 seconds on network news, a sixty-second piece on Brian Williams’ nightly news two days in a row. In other words, if you looked down to see if there was any mashed potatoes left, you missed it.

MJ: Most people did miss it, unfortunately. Do you think Americans have forgotten about Afghanistan because the media isn’t covering the violence there enough?

RS: Every time someone says this to me, the press aren’t doing a great job covering Afghanistan, I say, “Do you know about Hezb-Islami Gulbuddin? Or Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, one of the main enemy combatants there? His group is really who we’re going after, not Osama bin Laden.” People don’t know that. They bought into the marketing of the war, “We’re hunting Osama.” We’re not hunting Osama. In the whole year I was there I didn’t hear one person mention Osama with any credibility, like we’re going after him. They’re low-level thugs, criminals, warlords, people profiting off poppy trade, people attacking our soldiers, people intimidating the people by killing teachers and local officials — that’s who we go after. They always say, “We’re going after high-value targets.” I was in some pretty interesting circles over there, and not once did I hear anyone say we’re going after Osama. If there are guys going after him, its kept pretty covert because in general circles it’s Hezb-Islami Gulbuddin, led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

MJ: You mean, Osama bin Laden is now just this bogeyman used to manipulate public opinion?

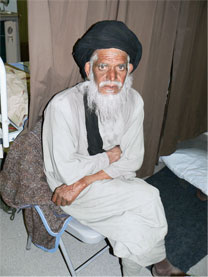

RS: I judge everything by my mother. She’s an intelligent lady, an R.N., not stupid but knows nothing about foreign policy. She’s got to get up everyday and go to work and go shopping and carry on with her every day life. How does she understand this great adventure we’re on, especially in Afghanistan? We didn’t study it in school, we don’t really know about the people, the culture, the language, what are the local problems over there, and we certainly don’t know enough about the terrorists who want to change our society or bring down our evil western ways, as they say. They do like they’ve done in every war: They label it, and they market it. It’s all about marketing. Let’s put it this way, every time you see a guy with a beard, a turban, and a camouflage jacket, he’s Osama, the bad guy, and everyone who looks anything like him must be the bad guy. Al Qaeda’s the bad guys. That’s who we’re fighting because the brought down the buildings in Manhattan and the Pentagon. And, oh by the way, Saddam’s their cousin.

MJ: What are other ways to manipulate public opinion?

RS: Since I’ve been home, I still constantly monitor the news from Afghanistan and Iraq. Everyday I get the casualty lists. The thing that’s startling is that they’re masking the casualties, the cost of the war in Afghanistan. Iraq is bad enough, but Afghanistan — that was supposed to be the shining jewel of the war on terror. We went in kicked out the bad guys and set up a democracy and everything’s gonna be fine now.

MJ: What? Masking the casualties? I’ve never heard this before.

RS: It’s a public relations tactic. A news cycle lasts 48 to 72 hours. Say Johnny Smith from New Haven, Conn., is in Kunar Province where his American infantry battalion is operating. He’s in a fight with local insurgents — not Osama bin Laden, maybe some foreign fighters, but mostly local. Johnny Smith dies in combat. Within 24 hours there’s a news release that comes out of this island we call Kabul that says a coalition soldier was killed in Afghanistan today. We’re not going to give out his name because we’re going to say, “The next of kin have to be notified.” We’re not going to give out his nationality because we’re all part of this quote “coalition.”

But here’s the sad fact: 99.99 % of coalition forces in Kunar are in fact American. So now in the news — NBC news, national news, wire services — the only thing that’s released is that a “coalition” soldier was killed in Afghanistan today.

And 72 hours later when the DOD finally releases Private Johnny Smith’s name, the New Haven Register and Channel 8 will pick up the memorial service and how sad Johnny’s family is. But in San Francisco, they never hear about it. In Minnesota, they never hear about it. In Florida, they never hear about it. It’s a very clever public affairs strategy. Now we have NATO in Afghanistan, so it’s, “A NATO soldier died.”

MJ: Don’t you think they should withhold the name out of respect for the family?

RS: Something tells me that for an American soldier who gave his life on a hillside in Afghanistan, at the very least we can honor and respect the sacrifice that he made. Can’t we at the very least in society honor his sacrifice and realize that’s the price that we’re paying for the war that we’re waging? But instead he’s a nameless coalition soldier? It’s along the same lines as this idea that we can’t take photographs of flag-draped caskets. It’s the same concept. They don’t want to show the price being paid. They don’t want to show the caskets. They don’t want to name these people. And America as a whole goes on shopping.

MJ: You’ve interviewed families of fallen soldiers for Stars and Stripes. What did they say?

RS: One comes to mind. The father said to me, “I don’t need the government to protect me in this time of grieving.” Because that’s what they say: “It’s a time of grieving for the family,” so they don’t want to show the caskets coming home. They’re using the families as a scapegoat. His son was killed in Sadr City with the First Armored Division. He was killed… April 7, 2004. Do you remember when the woman snapped the photos in Kuwait and sent them to the Seattle paper?

MJ: Yeah.

RS: Well, he’s pretty sure his son was in one of the caskets in the picture, because his death happened around that time. He said to me flat out, “I think it’s an honor. I think we have to honor our young men and women.” When you see these ceremonies, they are the most solemn of ceremonies. It’s a funeral like you’ve never seen before. When you see combat soldiers raising one of their fallen, it’s historic in proportion. But America never gets to fully understand the impact, or people would have to face the fact that we’re in a war. And people don’t do that. One of the things I hate to hear in the news is, “and in stocks today.” Especially NPR, it always seems like they squish our guys just before the stock market.