Violence seems to love the line running through the Rio Grande at the twin cities of Laredo, Texas, and Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas.

The Mexican community was born in the humiliation of the US-Mexican War. When the peace treaty left the Spanish colonial town of Laredo on the American side of the river, Mexican patriots decamped to the southern bank and, legend has it, took their buried dead with them. That favorite murder song “The Streets of Laredo” migrated from Great Britain (“The Unfortunate Rake”) to New Orleans (“St. James Infirmary”) and to Texas, where it mutated into the classic cowboy ballad of dying by the gun. As I walked out in the streets of Laredo, As I walked out in Laredo one day, I spied a poor cowboy wrapped up in white linen, Wrapped up in white linen, as cold as the clay.

Now Nuevo Laredo has become the line between two major Mexican drug cartels, and every day new lyrics are written in blood to a lament we all know but fail to face. Bullets killed the police chief last summer, just a few hours after he took office. This brought in the Mexican army. The ongoing slaughter of many cops and citizens caused the US government to shut down its consulate for a spell last August. This winter the local paper was visited by some strange men, presumably working for the cartels, and they fired dozens of rounds and tossed in a grenade. One reporter took five bullets. The editor promptly announced a new policy: His paper, one of the few Mexican publications on the line actually printing news about the drug cartels, would no longer report on the cartels. One major US daily had to evacuate a reporter after getting what editors termed “creditable death threats.” Dozens of US citizens from neighboring Laredo have vanished while visiting Nuevo Laredo. This January the city experienced, at a minimum, 20 cartel killings.

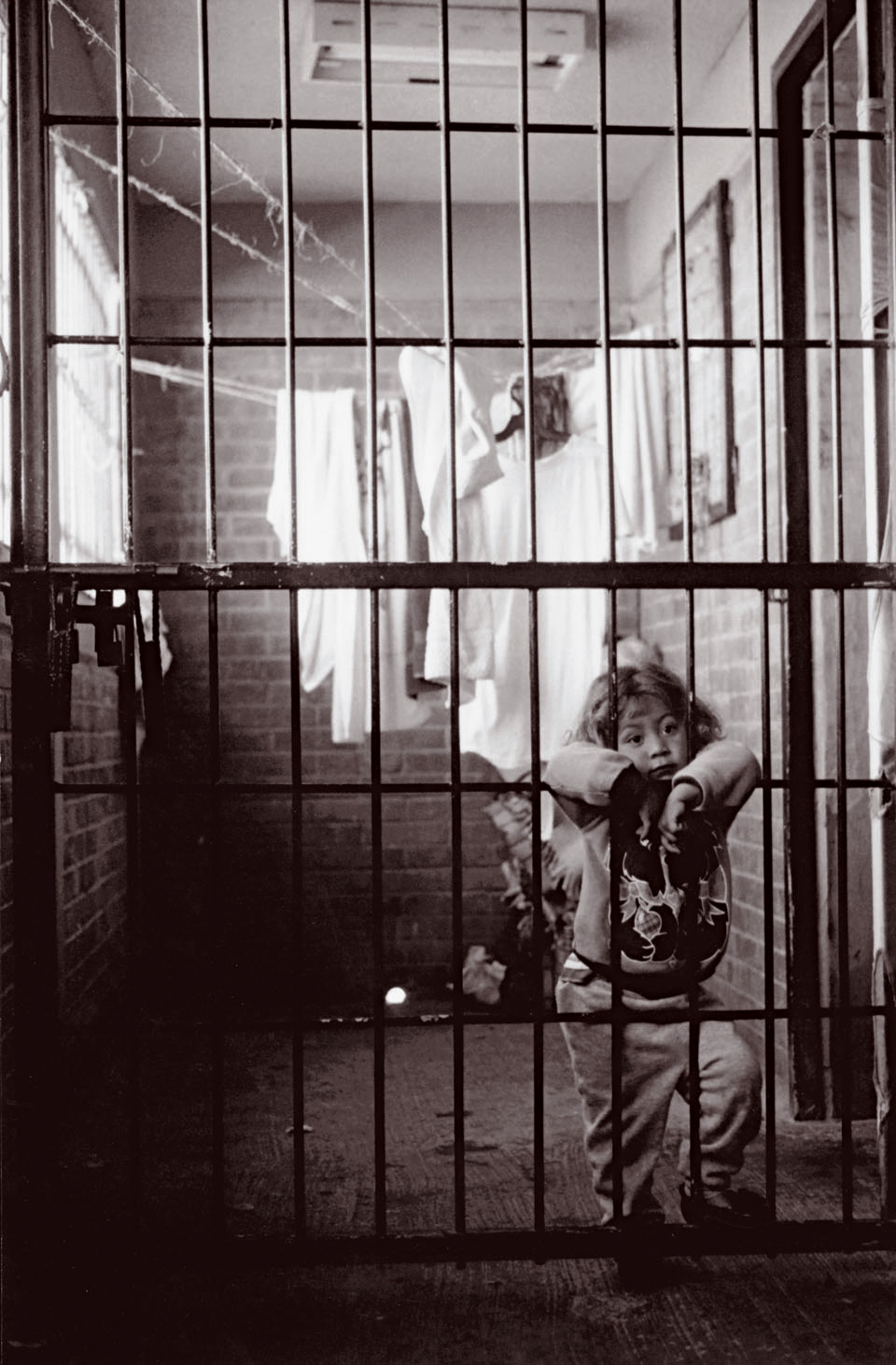

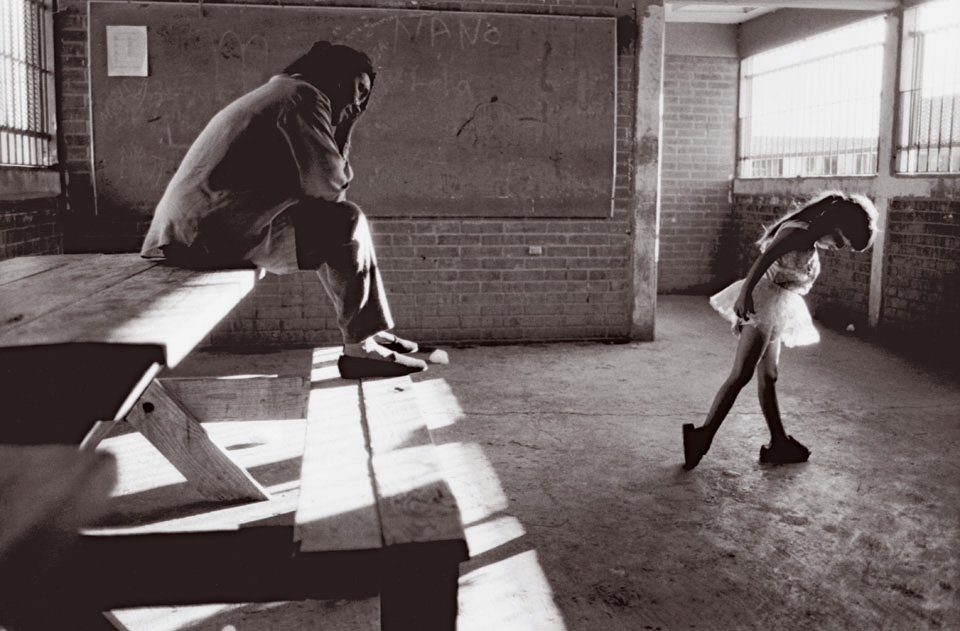

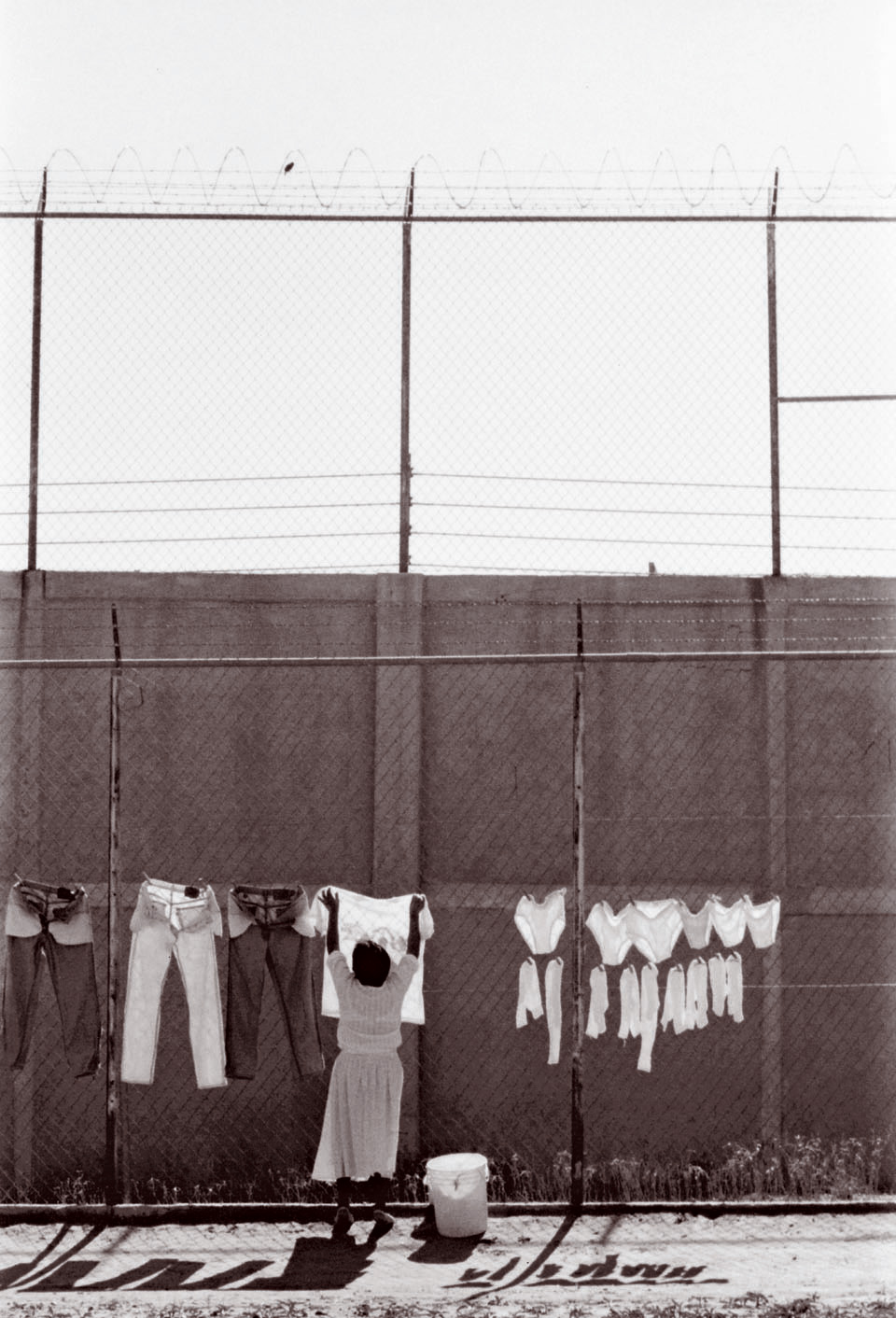

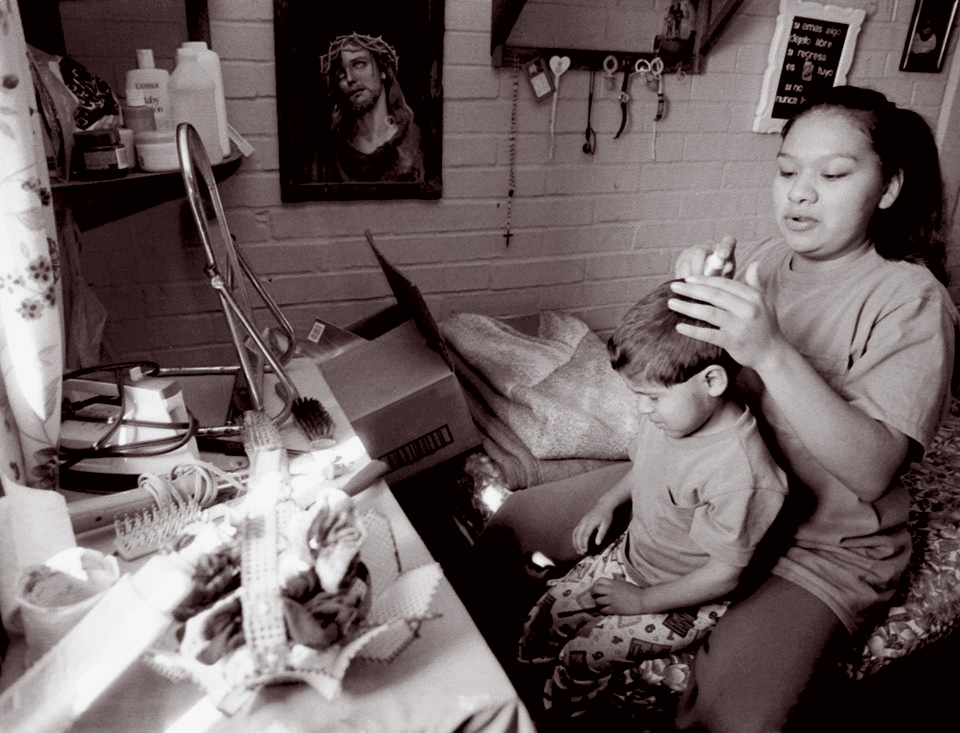

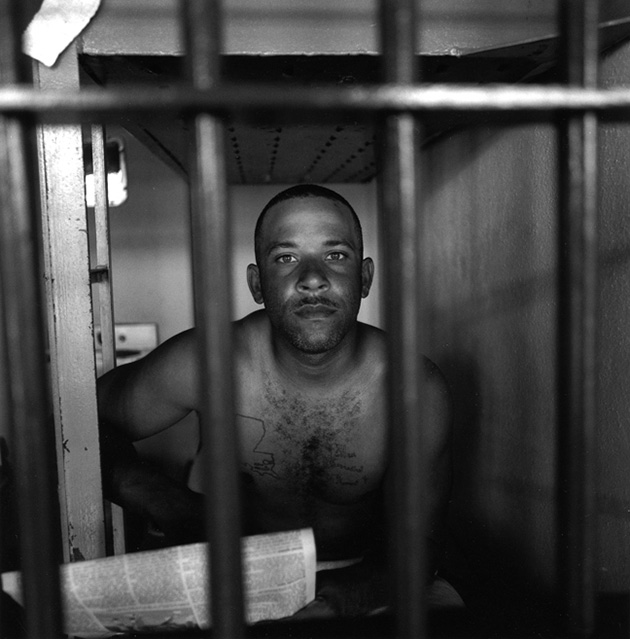

Beneath this gore, women and children muddle on, some in Mexican jails. Incarceration, like law, is a bit different in Mexico. Conjugal visits are permitted; small children younger than six can be locked up with their moms; and men and women peddle goods and themselves within the walls in order to survive. Mexican prisons often do not provide grub. I’ve stood in line with family members who toted a week’s supply of food on visiting day, seen women reel out of cells in disarray after their weekly intercourse sessions with their men. Drugs are commonplace inside the walls, as are gangs. Money can buy anything.

For years the US Drug Enforcement Administration has complained about the posh quarters given to major drug players and how they continue to do business without interference while theoretically being under lock and key. The women may come in clean, but they don’t stay that way. In Nuevo Laredo, they’re high by 10 a.m., then they spruce up and go off to the men’s area to make some money. By afternoon they return, their necks laced with hickeys. Convicts run the prison, and the guards do as they are told by the dominant inmates. People get killed. And all this goes on with toddlers underfoot.

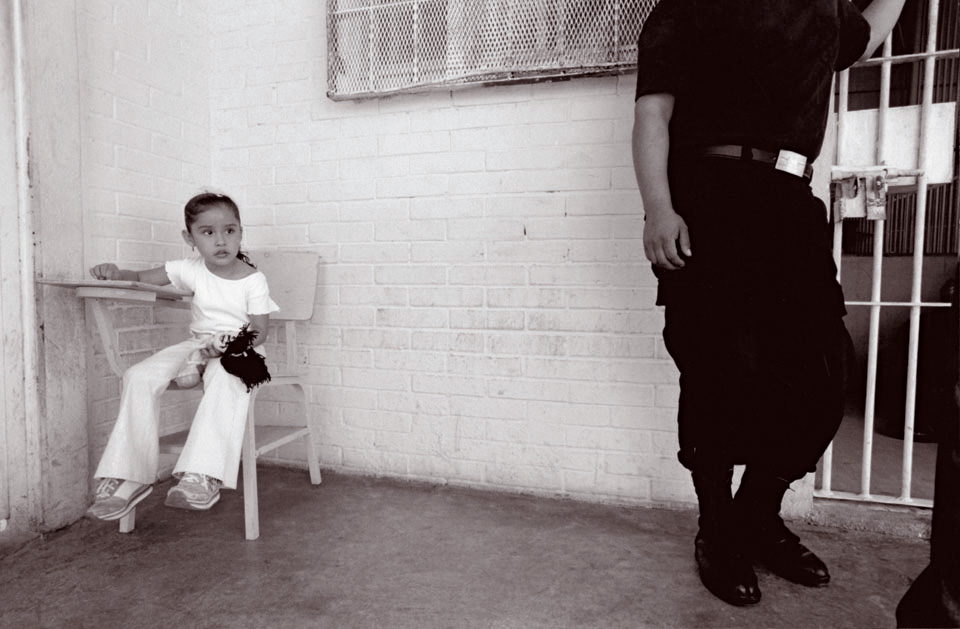

In Nuevo Laredo’s El Penal II, the cells currently hold 71 women. Some get pregnant while inside. At any one time, there are 4 to 10 kids living behind bars. For many, their options are limited: Go to prison with mom, or go to an orphanage. Once the children reach age six, they are tossed out. Photographer Penny De Los Santos put it this way: “It’s a bad place for kids. These people are in here for murder. Kids have the run of the place, kids are golden, spoiled, but one child might have several caretakers. It’s definitely not safe. Men come and go out of the women’s area all day long.”

This is an ancient story on the line and one that is traditionally ignored by both the press and the public. And it can get worse. In January 2005, after President Vicente Fox implied he was going to break the cartels’ hold over the penitentiaries, cartel thugs kidnapped six prison employees in the border town of Matamoros and dumped their bodies at the prison gates. And so we catch hints of things in brief news flashes. Hear truncated tales from time to time. And then we forget and go back to our various wars—our war on drugs, our war against illegal immigration, our war for homeland security. Meanwhile, the women rise, get high, go to the men. Children play amid adult shouts and screams and moans of pleasure. Murders go down. Free trade flows down its licit and illicit lanes. We’re left with these photographs and they are rarities since Mexican prisons do not welcome cameras or the press.

We sense what happens to women who are forced to live this way. But we don’t really know what becomes of children who are given this kind of a start in life. Twenty years ago, a man was executed by fellow drug people on the border after a career of 50 or 60 killings. He began his bloody career when he was 13 and was then stuffed into an adult Mexican prison. I remember going to the cops in that Mexican border town and cajoling my way in to see his mug shot and rap sheet, all this while a prisoner screamed under torture in the next room. The 13-year-old killer made it all the way to age 27. He never used a gun. He favored scissors or a screwdriver.

I look at these pictures and I wonder what will become of these children. But I don’t really wonder at all.