Photographs by: Joseph Rodriguez

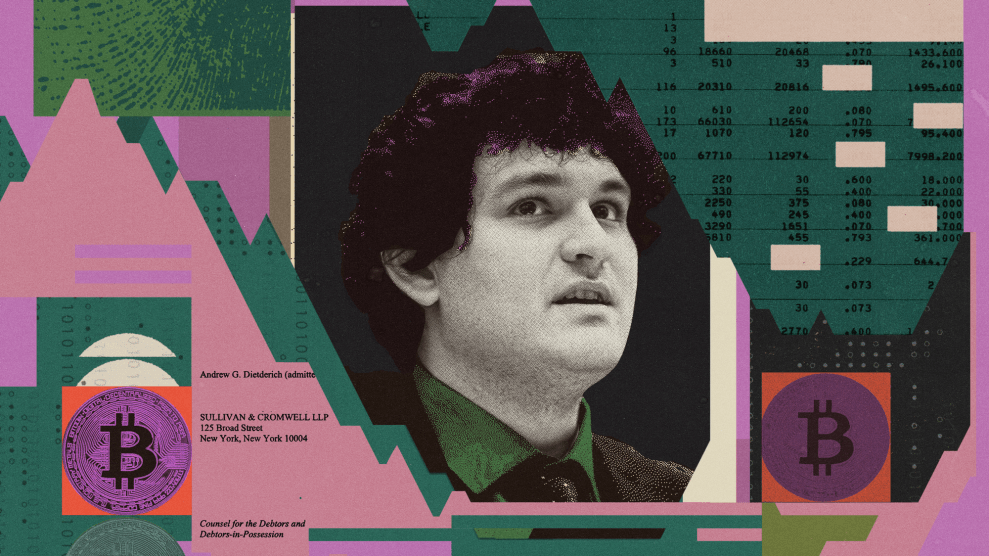

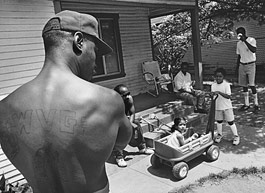

AMONG THE COMPETING STORIES about how to stop gangbangers from slaughtering each other, here’s the leading contender from the street: Sometime in ’77 or ’78, at a South Central L.A. junior high, a Grape Street Crip named Loaf, from the Jordan Downs housing project, sticks a knife into a Bounty Hunter Blood named Night Owl, from Nickerson Gardens, killing him on the spot. One bloody reprisal leads to a hundred bloody more, feuds spread through the two other big Watts projects—Imperial Courts, home of the PJ Crips, and Hacienda Village, home of the Circle City Pirus. With all of them warring against each other—Crip against Crip, Crip against Blood—and the crack wars raging, and L.A. gunslingers wasting 800 people in 1992 alone, Watts becomes the national epicenter of the shadow fantasy that lives in the heart of every American, that Boyz N the Hood dystopia in which lunatic teenagers troll the streets with AK-47s, gunning down suckers without remorse. To be hopeful is to be a fool—it’s all going to hell, steer clear—but, to hear Aqeela Sherrills tell it, the answer comes from the black community itself. First, Louis Farrakhan introduces a handful of rival gangbangers to Jim Brown, the retired NFL Hall of Fame running back. Brown directs a self-empowerment nonprofit called Amer-I-Can, and he starts inviting the four gangs up to his posh Hollywood home, feeding them pizza around the pool and pushing them to lay down arms. It’s not all love and kisses: One of the PJ Crip OGs, a guy named Tony Bogard, had just shot and killed a Grape, and the Grapes riddle Bogard in return, though not fatally. But Daude Sherrills, Aqeela’s older brother and a Grape OG, finally writes a cease-fire treaty based on the text of the Israel-Egypt truce of 1949. The only thing left is to make it real, to walk each other’s streets without fear, and it’s Aqeela who actually talks a handful of his fellow Grapes into the unthinkable: driving down to Imperial Courts and stepping into the broad daylight of the PJs’ turf.

As soon as they show up, Aqeela says, people start running into their houses, yelling, “All the cats from Jordan Downs over here!” But then Bogard emerges, demanding they step into the gym for a conference. “He was talking about how, ‘This can’t happen just like this! It’s going to take years! I just got shot up!'” Aqeela recalls. “But our Gs was over there, too. A lot of these cats is dead now, but they had a higher level of consciousness, and they was all just like, ‘Fuck that shit, you know, we ain’t never going to heal all that! That’s in the past. We got to make this shit right for the little homies.’ I was 25 at the time, so a lot of us young cats was like, ‘Man, let these old niggas stand in the gym and talk. Niggas ain’t going to shoot nobody, let’s go outside.'” So they do. They walk right into a crowd of PJs. “The young cats from the Imperial Courts,” Aqeela says, “they was like, ‘Man, you all wit it? You all wit the peace?’ And we was like, ‘Yeah, we wit it!'”

Right then, in Aqeela’s memory, “it was like, ‘Fuck it, it’s on!’ People yelling it, house to house, it was unbelievable, you could see people coming outside, ‘It’s on! The peace treaty on!’ Mobs of people driving up, girls seeing dudes they been wanting to see for years.” By the next morning, which was also the day the Rodney King riots erupted, the cease-fire party had rolled back to Jordan Downs, the Circle City Pirus had shown up to make amends, and yes, even the Bounty Hunters, all those years later, came just to let bygones be bygones. “There were so many peace-treaty babies, it was ridiculous!” says Sherrills.

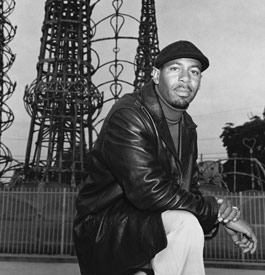

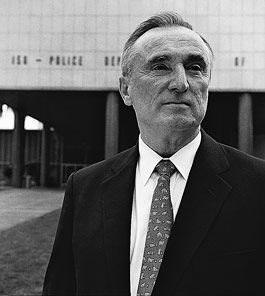

Aqeela Sherrills, gang member and street worker, in front of the Watts Towers

And here’s why this story matters: Gang violence plummeted nationwide in the years that followed, along with an overall drop in violent crime, but while the overall number remains stable, youth homicide is rising again. Since the late 1990s, in fact, the only demographic to see an increase in murder victims is men between the ages of 25 and 34, and 67 percent of killings between young men are gang-related. According to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report for 2004, the latest with complete data, juvenile gang homicides have jumped 23 percent since 2000. And there’s no new drug epidemic to explain the change, nor is it confined to the ghetto. Much of the new gang activity is occurring in the affluent D.C. suburbs, sleepy Provo, Utah, even the Northern California wine country, which has provoked a new round of that old hand-wringing about how our kids got to be so psychopathic, and why we return again and again to this same awful place. If we brought down the violence before, one can’t help wondering, why can’t we bring it down again? And that’s why the story of the so-called Watts truce is so important: In the dysfunctional national conversation about how to move forward, it turns out that none of the leading players can agree on what worked last time, what exactly is happening this time, or, least of all, what to do next.

“People who really understand the street,” according to professor David Kennedy of New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, “all understand a fundamental truth: that the stories we tell about gang violence are wrong. There are a couple of basic ones, and they’re all wrong.”

TALK TO LOS ANGELES POLICE Chief William Bratton, the former New York City police commissioner who currently has jurisdiction over the largest gang-violence problem in the world, and you get a picture of enormous, well-organized gangs proliferating nationwide and even internationally. A veteran of New York’s crackdown on the Sicilian Mafia, of Boston’s early successful experiment with community policing, and of New York’s now-famous “Broken Windows” approach to stopping urban decay, Bratton has successfully encouraged the FBI to develop a new “National Gang Strategy.” Targeting the biggest and most advanced gangs with a combination of RICO prose-cution, intelligence gathering, and special investigative techniques, the FBI’s new approach is modeled after those used on traditional organized crime—”something that I’ve been advocating since I came to Los Angeles and saw the scope of the problem,” Bratton says. “It was quite clear that it had grown to national proportion, so that gangs that began here in L.A. or Chicago had now begun to spring up in other areas.” Local police departments, in Bratton’s view, are simply too limited in their jurisdiction. “The tools that the feds can bring into the equation,” he says, “their investigative powers, their sentencing powers, it would be crazy not to take advantage of that. I had experienced that in New York, working with the FBI in their attack on the old-style mafias, and how they were able to break their backs, and the belief that you could use many of the same prescriptions against these gangs, whether they be Latino or African American, the two principal groups I have to deal with here.” To that end, in fact, an FBI task force has just been established specifically to dismantle Mara Salvatrucha, a.k.a. MS-13, an international gang that started among Salvadoran immigrants in Los Angeles.

In South Central L.A., a gang-intervention counselor talks with a youth named Kemo, who was later killed.

But to hear it from people on the street, like Aqeela Sherrills, who has become a national figure in grassroots peace activism, speaking at dozens of conferences as far away as Croatia, running a Watts-based nonprofit that brokers truces between gangs all over the country, and meeting with the likes of director Michelangelo Antonioni and Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams, Bratton is missing the point. The mid-’90s drop in crime, in the view of Sherrills, happened not because of any top-down policing strategy but because thousands of men and women just like Sherrills, in a homegrown, street-level effort now called the urban peace movement, began devoting their lives to the tedious work of defusing conflict, day in and day out. Most gangs, they’ll tell you, are less about drug dealing or violence than about community, desperate young people looking for surrogate families.

“A lot of people think that there’s a level of sophistication within the gang culture like the Mafia,” Sherrills says. “Not at all. There’s no organization, there’s no nothing.” The Crips gang, Sherrills insists, admitting that he is still a member, “is not a sophisticated entity in any way. There’s probably 1,200 cats in my neighborhood, and it’s all broken up into cliques. So you got the Parolees, the Peta Roll Squad, the Boss Players, you got the Tiny Locs, and they all claim Grape. But they all in they own cliques. And you got the jackals in the neighborhood, people who rob folks, the drug dealers, the peacemakers, and then you got the killers. Individuals who are known, who shoot people.” Responsibility for the new upsurge in violence, in Sherrills’ view, has nothing to do with the gangs at all. It has to do with the system, with America’s ongoing refusal to address poverty and racism, its continuing manipulation by the prison-industrial complex, and the government’s betrayal of peacemakers, switching funding back over to the construction of jails and the arming of police forces.

L.A. Police Chief William Bratton

Kennedy, a leading academic criminologist and the architect of the only anti-gang-violence strategy that has ever worked against modern street gangs, shares much of Sherrills’ view. As chief designer of Operation Ceasefire, Kennedy presided over a public-private antiviolence initiative that got such dazzling results, so fast, that it is now known in law enforcement circles as the “Boston Miracle.” Using a mix of prosecutorial and psychological tactics, Ceasefire has since been replicated in so many small to medium-sized cities that it has emerged as academic criminology’s answer to the urban peace movement, the favored gang-crime control strategy of the intellectual best and brightest. And like Sherrills, Kennedy sees the emphasis on huge, hyperorganized crime syndicates as a red herring, a distraction from the real engine behind the routine murder of young men in American cities, and a product of the misconceptions that the public and the police have about gangs.

The first of these misconceptions, Kennedy says, echoing Sherrills, is that gang members are murderous superpredators. “That’s not true,” he says. “One of the interesting things about these guys is that if you can pull one aside and talk to him away from his boys, they start talking about how shit-scared they are, and how they don’t like this stuff, but if they don’t act in certain ways their friends and their enemies all turn on them. You get the occasional psychopath, but most of these guys do not have the same commitment to violence that they might to making money on the street.” In the words of T. Rodgers, founder of the Bloods crew in the notorious “Jungle” neighborhood, where Training Day was set, there are only two kinds of gang members, “cowards and kids, and both of them just want attention.”

“Another story is that it’s all about drugs,” Kennedy says, “and that’s not true either.” While most gang members do participate in the drug trade, the popular image of Crips and Bloods battling for crack-dealing turf is as outdated as the movie Colors. Nor, in Kennedy’s view, is gang violence a sickness somehow endemic to ghetto culture—”because almost everybody in these neighborhoods doesn’t participate. Hardly anybody goes this way.” In Boston, Kennedy found that even within the most gang-dominated neighborhoods, fewer than 5 percent of young men were gang members. A 2004 outburst of gang killings in San Francisco produced a similar finding: Only about 100 young men in the entire city were thought to be truly dangerous, and a couple dozen were thought to have done most of the killing. “But because almost everybody deals with one or another of those fictions,” Kennedy says, “it’s very hard to engage with what’s really going on.”

In East L.A., Porky and Pony of the Marianna Maravilla gang

What’s really going on, in Kennedy’s view, is small groups of young men encouraging each other to violence. “It’s about respect,” he says. “It’s about boy-girl stuff, it’s Hatfield and McCoy.” This, too, is nearly uni-versal among people on the front lines, from Sherrills to T. Rodgers to former police captain Rick Bruce in San Francisco’s notorious Hunters Point neighborhood: Gang killings are not about huge, hierarchical cri-minal organizations struggling for control of drug-dealing turf. They’re about beefs. They’re about patterned webs of vendettas and retaliations. Somebody looks at somebody wrong, or two guys want the same girl, and it’s on. In San Francisco, for example, nearly 20 tit-for-tat homicides over the past decade have been traced back to a single car auction, after which a gangster killed a man who outbid him for a vehicle. “You have to keep in mind,” says T. Rodgers, “that between the ages of 11 and 17 they’re warriors untried. From 17 to 21, it’s ‘What’s your claim to fame? I can impregnate every girl on the block. Or I can knock you out with a right or a left.'” It’s what University of California-Irvine criminologist George Tita calls “expressive violence rather than instrumental violence.” Tita says that even among gangs that are involved in the drug trade—and most are, in some way or other—the leaders will gladly negotiate trade agreements with one another even as their foot soldiers murder each other over petty slights, because strict street codes dictate a violent response to nearly any perceived insult and every individual is terrified of falling short of those codes. But because group psychology, among a relatively small number of young men, is the clear engine of an enormous percentage of urban violence, it’s a perfect point of intervention.

KENNEDY WAS A RESEARCHER at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government in the early ’90s, when the Bounty Hunters and Grapes were gunning each other down and gangs in Boston’s poor neighborhoods started doing much the same. The city’s response, throughout the early 1990s, was like a blind grope through crime-control strategies. In addition to stop-and-search policies for all suspicious young black men and halfhearted attempts at community policing, there were street workers like the Sherrills brothers talking down gangbangers, even a powerful outreach effort by a coalition of churches, galvanized by a killing during a church memorial for a murdered gang member. Good stuff, and crucial to the success that came later, but it all amounted to gathering the pieces of a puzzle without putting them together—until 1994, when the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) funded Kennedy and his colleagues.

They started by forming a working group of all the law enforcement and community elements already involved—street workers, juvenile corrections, clergy, probation, parole, police—and even added a few, like the DEA. Then, in March 1996, when fighting between rival factions of the Vamp Hill Kings killed three gang members in the space of a month, they made a quick series of arrests, with help from the ATF and even local school police, and held a forum with virtually the entire membership of the Vamp Hill Kings. Supported by local clergy and community members, the working group then did what Kennedy calls “retailing the message.” The message went like this: Violence stops now, the adults are taking over, and the new penalty structure says that if anybody in your gang puts a body on the ground, the whole crew pays, and fast. Every unserved trespassing warrant will get served; every petty parole or probation violation will get enforced; smoke a joint in public housing and you’ll get evicted; open a single beer on the street or piss on the sidewalk and you’ll go to jail. With the help of street workers, Kennedy’s working group also made it clear to the Vamp Hill Kings, and soon after to other gangs, that this was not an indiscriminate war on gangs. It was a crackdown on violence alone. Gangs that didn’t indulge in violence would be spared. And everyone was getting the same story, so if you chose not to retaliate for a slight, you had an honorable excuse: Your whole crew would go down. Flyers at the forum described a gangster named Freddy Cardoza who’d just gotten 20 years without parole for being caught with a single bullet. The working group balanced the stick with the carrot of job-training services.

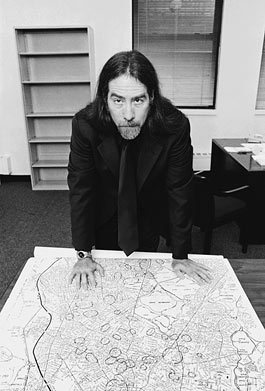

Criminologist and Operation Ceasefire architect David Kennedy

The point was to leverage group psychology in such a way that the group itself would have an interest in discouraging violence. It was wildly successful. Within 12 months of the Vamp Hill Kings forum, youth homicides in Boston dropped by 73 percent. In little over a year, Operation Ceasefire returned Boston’s youth homicide rate to a place it hadn’t been in decades. And in much the way the Watts truce triggered a nationwide paroxysm of truce-making, Attorney General Janet Reno started talking about a nationwide rollout of Operation Ceasefire. More than a dozen smallish cities have actually done it, with stunning results. Indianapolis, for example, saw a 40 percent drop in its annual murder rate, and Rochester, New York, in 2004, saw a one-year drop, from 31 to 9, in the number of young black males murdered. In February 2004, a long-planned Ceasefire intervention for the nation’s capital was triggered into action when a gunslinger from a gang that terrorized the Sursum Corda (Latin for “lift up your heart”) housing project shot a 14-year-old girl who was a witness to an earlier shooting. Within days, 36 gang members had been arrested on drug conspiracy charges, and dozens of other gangs had been contacted to make sure they understood exactly what had happened to the Sursum Corda gang—and how to avoid a similar fate.

BUT HERE’S THE RUB: Ceasefire, which is also known as the “pulling levers” approach because it involves a simultaneous pulling of all the relevant levers on violence, is very hard to hold together. Our government is built around the parsing out of human life, assigning our need for shelter to one agency, our need for law enforcement to another, our health and employment and education to still others. Getting all those agencies to work together—asking government to address the complex nature of a human life, in a holistic fashion—requires extraordinary commitment from all parties involved. And as soon as you get a new U.S. attorney with other priorities, or your housing authority gets caught up in a distracting scandal, or a lowered crime rate encourages a redistribution of funding, things fall apart. Boston itself saw a 67 percent rise in homicides in 2001, to a near doubling of the 1999 rate. Something similar is happening now in Rochester, with gang violence roaring back after a one-year hiatus. In both cases, Kennedy gives credit for the initial success to everything that’s right about Ceasefire—new Ceasefire interventions continue to have dazzling success—and he blames the subsequent failures that have occurred to the loss of momentum that comes with complacency. “As it existed in 1996 or 1997, Ceasefire is entirely gone,” Kennedy has said, speaking of Boston. With funding from the NIJ, George Tita and the RAND Corporation ran a pilot Ceasefire program in an L.A. neighborhood that followed the same pattern: After initial success, the working group drifted apart, and nobody in law enforcement or the community took responsibility for keeping it alive.

All this makes it easy for Bratton and L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca to dismiss Ceasefire as having little relevance to Los Angeles, which is significant to the overall national picture because, at some level, Los Angeles is the national picture. Accounting for 75 percent of all 10,000 youth gang homicides committed in California between 1981 and 2001, Los Angeles also accounted for fully 30 percent of the entire mid-1990s drop in the national youth-homicide rate; remove Los Angeles from the picture, and the story is very different, with equal numbers of cities reporting declines and surges in youth homicide. Individual Los Angeles gangs are also dramatically larger in membership than gangs elsewhere, they do spawn copycat gangs in other parts of the country, and they are so deeply entrenched as to be almost like community organizations. As Bratton points out, L.A. now exports Crips, Bloods, and L.A.-branded Latino gangs not only to every major city in the United States—and to most minor ones—but to Canada and Mexico. Aqeela and Daude Sherrills, in fact, were invited to New Jersey last year to work as peacemakers precisely because one of the warring Newark Crip factions was calling itself Grape Street, even though none of the Newark Grapes had ever been to the Sherrills’ neighborhood. (Aqeela tells a funny story about Newark Crips asking him about various secret handshakes and rituals they’d learned, wanting to be sure it was all authentic: He’d never seen any of it before.)

Trying to stop American gang violence without stopping it in L.A., in other words, is like trying to reduce global warming with no help from the United States. But if you so much as mention Operation Ceasefire in Los Angeles law enforcement circles, you find a thinly concealed contempt. Baca, who recently helped the Crips and the Bloods reaffirm the 1992 truce, calls the Boston strategy “good for a community that has 50 or less murders a year. I would wish that we had that small a problem in L.A. We have 500-plus gang-related murders a year…spread out over 800 square miles.” Baca’s own prescription leans toward the liberal—a personal commitment to various nonprofits that teach so-called “life skills” to troubled youth, offering counseling and job training, and mentoring from police officers. Bratton, who is arguably the most important law enforcement official in the United States on the issue of gangs, is equally dismissive of Ceasefire. “There’s no magic bullet,” he says. “There is no single solution. And while the patient may exhibit similar characteristics, what might work in Boston may or may not work in Los Angeles. Boston’s gang problem is very small. I’ve got 50,000 gang members versus Boston’s couple of hundred.”

As for his limited interest in street workers like Sherrills, Bratton wouldn’t be the only one with uncertainty about their effectiveness. It’s not that anyone thinks their work isn’t helpful, but there’s no consensus on how instrumental it is, largely because nobody can get any data. Criminologist Tita, for example, takes the work of urban peacemakers so seriously that he has a photocopy of the original Watts truce hanging on his office wall—the one drafted in part by Daude Sherrills—and he keeps a database of 40 years’ worth of Watts homicide statistics.

“And look, trust me,” Tita says. “I’ve done the literature search. I’m still looking for—and I have the opportunity to write—the very first real evaluation of a gangs truce. Tell the Sherrills brothers that I’m begging them to come down and meet with me and let’s design it together so that there’s no ambiguity.” But for whatever reason, Tita says, they haven’t heeded that call. And with the data Tita does have, he cannot find a single statistically significant effect of the Watts truce. “I even looked at the gangs that signed the treaty versus the other gangs in the community,” he says. “Did their rates of participation as homicide victims or offenders change? I couldn’t find that either.”

The problem with truces, according to T. Rodgers, who still does gang-outreach work in the Jungle, is that “there’s always a kid in the back of the group that says, ‘Fuck that shit.’ And that’s all it takes.” But Rodgers bridles at the suggestion that he needs evidence to prove the worth of what he does. “I’m just going to say it,” he growls. “White folks come in with a magnifying glass and always want to know how shit works with a MacGyver theory. And some things just don’t work like that. Some things are acts of God, some things are behavioral miracles.” He claims 60 to 70 percent effectiveness in getting gangbanging kids to go straight. “But I didn’t track them,” he admits. “I’m not the RAND Corporation. I’m just a street worker.”

Aqeela Sherrills feels the same way. “Even though the peace in the neighborhood is fragile as fuck,” he says, “we maintain it, through dialogue and conversation, and it don’t mean ain’t nobody getting shot. It means that’s all part of the process, that peace is not a destination. It’s a journey, like life. And there’s a movement in this country that wants everybody to see things through this lens, that if things aren’t like this, then it ain’t real. But as long as we can consistently come back to the table and have a conversation, the peace exists. As long as I can walk into the Nickerson Gardens and talk to those cats over there, it’s on. As long as we can go holler at Sister and PJ Steve, it’s on. As long as we can talk to Daude and Big Tank and Cal Boneski and the key brothers at Jordan Downs, the peace is fucking on. And that’s our reality. Because if people really knew what the fuck it was like around here, you know, man, they’d cry every fucking day.”

ACCORDING TO A 2002 REPORT from the National Institute of Justice, gathering 10 years of gang-related research, the view of street gangs as akin to the Mafia is indeed misguided. Data from a survey among almost 300 large police departments and members of four large Chicago and San Diego gangs found that while a few gangs—MS-13 would be one—are very large and organized, the vast majority show “little evidence of evolution into formal organizations resembling traditional organized crime. Instead, the gangs appeared to represent an adaptive or organic form of organization, featuring diffuse leadership and continuity despite the absence of hierarchy.” Most gangs, in other words, are just a bunch of guys hanging out on the corner.

The NIJ report, titled “Responding to Gangs: Evaluation and Research,” also found that traditional “get tough on crime” approaches—like the mass arrests of gang members and specialized gang task forces currently being directed at MS-13—have literally zero measurable impact on overall gang violence. (As if to prove the point, a press conference by Sheriff Baca, trumpeting the success of a recent anti-gang street sweep, was marred by simultaneous news of three Compton homicides.) Ditto for the Gang Deterrence and Community Protection Act, the draconian bill passed by Congress in 2005, which defines a gang as having as few as three members—just enough to make a federal conspiracy case—calls for stiff mandatory minimum sentences for gang-related crimes, and puts tens of millions toward prisons: The NIJ report shows conclusively that exaggerated jail terms have no deterrent effect at all.

The only responses that were found to be successful were the “life skills” programs that Sheriff Baca advocates, teaching conflict resolution and positive self-esteem, and, to a much greater degree, the Boston Ceasefire intervention. Ceasefire, in fact, is the only strategy singled out in the entire report as having caused a substantial reduction in youth homicide, and yet Bratton and the FBI appear utterly uninterested. Bratton is also ignoring a report commissioned by the California Attorney General’s Office—”Gang Homicide in L.A., 1981-2001″—written in part by George Tita and released in 2004, which concluded with a single, strong recommendation: that L.A. adopt a Boston Ceasefire approach.

This may have to do with the past experience of various players—Bratton headed the Boston Police Department when gang killings had the whole city in a panic, and he left shortly before Ceasefire took effect and made Boston famous for solving the problem. He was also part of New York’s “Broken Windows” successes and glamorous takedowns of the Mafia. One approach has worked very, very well for him, in other words, and the other has been mostly somebody else’s baby. But Kennedy places the blame on less personal habits of thought. Most of us, he says, jump to one of two very different responses to crime: the criminal justice response, which is all about the moral responsibility of individuals and the belief that tougher enforcement can influence those individuals; or the root-cause approach, which emphasizes the role of racism and economic inequality in crime.

The problem, Kennedy says, is that neither approach leads to an effective crime-control strategy. The criminal justice framework has no way of accounting for the fact that gang crime is overwhelmingly about “incidents in response to incidents in response to incidents that happened before, and which will affect incidents which will happen later,” and the root-cause framework ignores the fact that some people simply do need to be locked up. The criminal justice framework does make room for attacking certain groups—as in the anti-racketeering and conspiracy cases that brought down the Mafia and that are now at the center of the FBI’s anti-gang strategy. But these cases will never solve the problem if they are not combined with a larger response that targets group psychology. “I don’t have any sense,” Kennedy says, “that any of the people who put that together talked to anybody who knows about these issues.” As a result, Kennedy says, the FBI’s new war on gangs is “as tired as it can possibly be.”

The biggest problem, though, in Kennedy’s view, lies with the dysfunctional nature of American law enforcement. Comparing criminal justice to “a real profession, like medicine,” he points out that if there’d been a breakthrough in breast cancer treatment in Boston in the mid-1990s, and 70 percent of women who would have died of breast cancer were living, “then when people were talking about breast cancer in San Francisco they would not say, well, nobody’s made any headway on this, this is an intractable problem, we’re going to start from scratch. And if they did, then their patients would hold them accountable, but there is no mechanism like that in criminal justice. There is no real professionalism. How do you get to be a judge? Get a law degree. How do you get to be a DA? Get elected. There is no collective knowledge, no relationship between theory and practice. There was a time when surgeons were barbers, and what medicine did was bootstrap itself up. In criminal justice, we’re still barbers, and if people in these communities, paying the tax bills and burying their kids and visiting their raped daughters in intensive care, knew the way business was conducted, there would be bodies hanging from oak trees. The presumption that most people have, that this is serious, thoughtful work, and that if you don’t get good results it’s because absolutely nothing works, is so wrong. And if people really knew, I swear, there’d be blood running in the street.”