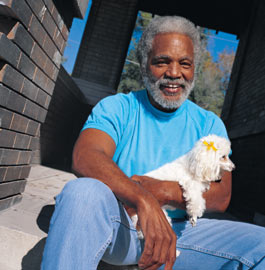

Photo: Michael Wilson

When Ernie Chambers returns to work this January, it will be with the knowledge that he isn’t long for the world, at least the world of the Nebraska Legislature, where he has served for 35 years, longer than any other member, current or past. Five years ago, Nebraskans passed a constitutional amendment calling for term limits. Unless the law is overturned, Chambers will be tossed out of office at the end of 2008. With his departure, the unicameral body (Nebraska is home to the nation’s sole one-house legislature) will lose more than institutional memory, because Chambers is distinctive, to start with, and does not attempt to blend in. He wears sweatshirts and jeans amid a forest of suits and ties; his gray beard contrasts with the clean chins of most of his brethren. He’s been described as “left of San Francisco” in a state that for decades has been tightly tucked under the blanket of conservative Republicanism. And, also, he’s black, the lone African American in the Legislature.

Depending on your perspective, that fact means everything or nothing. To Chambers, it is the characteristic by which his enemies, who are legion, define him, and for which they despise him. “They don’t like who I am, and they don’t like what I do,” he says.

But they do help him do it, albeit reluctantly. Because of Chambers, the Legislature routinely backs bills its members wouldn’t otherwise have dreamed of supporting. He cajoled his colleagues into abolishing corporal punishment in schools, correcting the state pension system so that women would be treated equally with men, and backing a switch from at-large municipal elections to district-based voting so that nonwhites would have a chance to serve. Under his sway, Nebraska led the nation in the 1980s in divesting in companies that did business with apartheid-era South Africa. Every session he introduces a bill calling for an end to the death penalty. He once got the Legislature to approve it, but could not overcome the governor’s veto. He later led the Legislature in halting the execution of juveniles and the mentally retarded, ahead of the U.S. Supreme Court’s nationwide bans.

Chambers is famous for an unsurpassed knowledge of legislative rules, which he uses to derail bills that threaten those he calls the “downtrodden.” This attracts the criticism that he is “the great obstructionist,” better at halting legislation than creating laws. As one colleague observed, “In Washington they call it a filibuster. In Lincoln, they call it Ernie.” Once, Chambers filibustered on the state budget until his colleagues agreed to set aside half a million dollars for a minority scholarship fund. In the 2005 session, he blocked the legalization of concealed weapons, as well as a constitutional amendment protecting the right to hunt, which he said would “trivialize and pollute” the state constitution. In classic Ernie Chambers style, he introduced a raft of riders to the amendment that would protect such other rights as “creating, recreating, conversating and procreating,” “hunting for the link between Noah’s Ark, Joan of Arc and Archimedes,” and “sitting on the front porch on a warm summer evening, drinking a glass of cold lemonade, dreamily watching the silvery moon rise to begin its journey across a darkening velvet sky powdered with stardust.”

Chambers’ mastery of oratory has gotten his arguments—in opposition to a state-paid government chaplain and in support of late-term abortions—cited in at least two cases argued before the U.S. Supreme Court. In the most recent session, he introduced an amendment to toughen the standards for DNA testing by police. The action came after officers in Omaha sought DNA samples from dozens of black men who roughly fit the description of a serial rapist. “Like an oversize dress, the description covers everything and touches nothing,” Chambers wrote in an opinion piece in a local newspaper. “A racial dragnet has been woven to justify random sweeps.” None of the men who were tested turned out to be a viable suspect. Chambers’ amendment required probable cause before a DNA test could be ordered and that samples be returned to those who are cleared. It passed 44-0.

With all that success, Chambers doesn’t feel overburdened with popularity. (One legislator frustrated by Chambers’ intransigence introduced an amendment that would have ceded Chambers’ Omaha district to Iowa.) Chambers feels the term-limit amendment was devised specifically to get rid of him. “This is Nebraska,” he says. “It’s a terrible place to be. It is an ultraconservative, ultra-racist state. I would not advise anybody black to come here.”

“Ernie sees racism when he pours his breakfast cereal,” responds Lee Rupp, a land manager from a rural district who served with Chambers for five years. “His problem is that he doesn’t think politically. He sees everything as right or wrong, with no shades of gray.” Others say Chambers’ perceptions are apt. “When Ernie gets under a person’s skin, which you can do through speech pretty effectively, one of the ways of responding to that is to bring up a racial issue,” says Vard Johnson, an attorney who served alongside Chambers for nine years. “I can tell you that in talking with my own constituents I would hear racially derogatory references made about Ernie Chambers.”

In the long run—and it’s been a very long run—Chambers may be as emblematic of his state as he is exceptional. “The Great Plains has a rich history of this sort of rabble-rousing individual,” says Gary Moulton, professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Chambers’ detractors should take heed of the state’s populist legacy, he says, one that includes William Jennings Bryan and other ad-vocates for the ignored and voiceless. “Ernie comes out of the ’60s, but if you take a step back you can see that it’s another aspect in the same populist vein,” Moulton says. “Instead of oppressed farmers it’s oppressed minorities.”

Unlike most of his colleagues, Chambers does not supplement his $12,000 legislative salary with other work. In 1984 Chambers successfully sued the state to get reimbursement for senators’ travel and food expenses, but they receive no pension or other benefits. “The Legislature here is a starvation deal,” says Rupp, who became a lobbyist after his stint in the capitol. “Everybody does it to put it on their résumé so they can go on to something else and make a living.”

Chambers, though, has stayed, logging 250,000 miles on his seven-year-old Honda Civic, commuting almost daily between his office in Lincoln and his two-bedroom apartment in a predominantly black district in Omaha. “I do it because I believe in it,” he says. In 2002, Chambers turned 65 and became eligible for Medicare; it was the first time in many years that he’d had health insurance. “I have not accumulated houses or stocks or bonds or anything; this has not been a lucrative office for me,” he says. “I entered the Legislature a poor man, and I will leave the Legislature a poor man.”