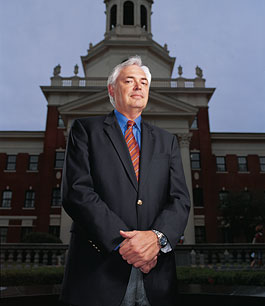

Photo: Wyatt McSpadden

“THERE IS A PASSAGE IN THE 25TH CHAPTER of Matthew that has always been meaningful to me,” Bill Underwood said. “It is a passage where Jesus is speaking to the disciples and he says, ‘I was hungry and you fed me, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was naked and you clothed me, I was without shelter and you took me in, I was in prison and you came to get me.’ The disciples say, ‘When, Lord? When did we do this?’ Jesus responds, ‘When you did this for the least of these, my brothers, you did it for me.’ ” Underwood paused and collected his thoughts. As a lawyer, a Christian, and a longtime law professor at Baylor University, the nation’s largest Baptist college, he was trying to explain, as we sat in his spare office on Baylor’s sprawling Waco, Texas, campus, “the ways my own faith manifests itself in my professional life.”

For years, that integration has meant such standard measures as doing pro bono defense work on death-penalty cases and leading students into an understanding of “how their faith might interact with their professions.” Then, this summer, that interaction became a much more pointed, and much more personal, issue for Underwood and his colleagues. The season saw the culmination of one of the biggest upheavals in Baylor’s 160-year history, a pitched battle between moderate and fundamentalist Christians for the soul of the university. In the course of the struggle, one university president fell, the theory of Intelligent Design (ID) was wedged into the curriculum and then railroaded out, the faculty went to the mat to defend its academic freedom policy, alumni groups splintered, and headlines across the state of Texas screamed blow-by-blow accounts.

And, in the end, Bill Underwood was appointed to run the university. As interim president, he is charged with overseeing an ongoing academic identity crisis hinging on a simple, central issue: What kind of university will Baylor be? In the process, unavoidably, he is also helping determine what kind of nation Americans will live in. Underwood’s new desk sits directly astride some of the larger rifts in American society: between academic freedom and religious orthodoxy, individual rights and communal standards, creationism and evolution. Many of those issues are popularly cast as contests between the secular state and religion. At Baylor, the argument is raging between the religious and the religious. Shattering progressives’ preconception that the evangelical Christian world is monolithic, Christian intellectuals, in this small microcosm, are engaged in a heated colloquy over the relationship of learning to faith.

THE CURRENT TROUBLES AT BAYLOR, Texas’ oldest university, began a decade ago, when Herbert Reynolds, a psychologist who had served as its president for 15 years, stepped down. In his place, Baylor’s Board of Regents appointed Robert Sloan, a smooth-talking conservative preacher who had been dean of the school’s seminary. Sloan ruled with an autocratic hand, according to complaints in the faculty senate. He also had an ambitious new vision for the school, a plan unveiled as “Baylor 2012.” With it, Sloan hoped to propel the school out of sleepy mediocrity and make it a top-tier institution.

For 160 years, the school has been cranking out the state’s teachers, lawyers, nurses, doctors, and politicians, awarding degrees guaranteed to open more “Lone Star” doors than a diploma from Princeton or Yale. This year the school ranks 78th in U.S. News & World Report’s annual survey of best universities, tied with the University of Colorado and ahead of the University of Massachusetts and American University. Still, Baylor garners blank stares when mentioned in New York or Cambridge—or for that matter almost anywhere outside of Texas. Baylor 2012 would rectify that. With pricey new building projects, more graduate programs, an increased attention to research, and a renewed emphasis on faith, Baylor’s name would become a household word.

The effort has left the 508-acre campus visibly divided. To one side lie the stately old buildings with columns and cornices that reference the school’s 1845 heritage. Porch swings hang from venerable pecan trees sprawling over shaded paths. While the dry Texas heat precludes ivy, the traditional architecture cries Harvard wannabe. On the other side of campus, the sun beats on new red-brick buildings with modern angles and minimalist steeples. Baby trees in wire playpens dot huge expanses of flat green lawn, and the architecture (ostentatiously supersized with budget materials) references the evangelical megachurches that erupt overnight in empty fields across the nation.

There are 12,000 undergraduates and 2,000 graduate students at Baylor. Ninety-four percent are from Texas, and 75 percent are white. Most are middle- or upper-middle-class kids, and most are Protestants—though Baptists themselves comprise slightly less than half of the student body. You don’t have to be Baptist to teach here—there are 78 Catholics, for example, on the faculty of 814. And the school is not “creedal,” the term applied to institutions where aspiring professors must sign a statement of faith subscribing to a religious doctrine. Still, teachers must agree to support Baylor’s mission, which is a Baptist one.

Baylor freshmen are required to go to chapel once a week. It’s assumed that, as Christian students, they will eschew drugs, alcohol, and sex. Dancing, once prohibited on campus, has been allowed since 1996. Homosexuality, however, is not, and gay students have lost scholarships and been disciplined. “It’s not up for debate with me,” Dean Paul Powell told the Associated Baptist Press about the policy. “I mean, you can talk about it, but the issue’s settled…. The Bible consistently says homosexuality is wrong.”

Still, Baylor fashions itself as “inclusive” rather than “exclusive.” A new national ad campaign seems to be trying to reach beyond its geeky Christian reputation to attract a broader (and hipper?) pool of applicants: One ad highlights the local Common Grounds café, congregating place for the school’s slim band of counterculture kids (whose hair color nevertheless remains natural, and whose piercings are limited to ears). Beneath the requisite warnings on the Common Grounds’ bathroom wall to “Please be neat and wipe the seat,” someone penned, “It’s the Lord’s will!”

So it’s no surprise that Baylor’s search for excellence would entail—along with such measures as increasing its endowment to $2 billion from $672 million, raising tuition until room and board now cost more than $25,000 a year, expanding its faculty, hiring more researchers, and creating a new science institute called the Polanyi Center—a certain religious quotient. Under the banner of Baylor 2012, Sloan began driving the school in a conservative direction. He decided to make Baylor more Baptist by hiring more Christian scholars (rather than simply scholars who are Christian) and grilling prospective professors on scripture, the depth of their religious faith, and their church attendance. Then, in 1999, Sloan circumvented the standard departmental peer-review process to appoint a professor named William Dembski as director of the new Polanyi Center. And with that, he, and Baylor, stepped right into the middle of a full-blown American fracas: the controversy over Intelligent Design.

INTELLIGENT DESIGN IS A nonscientific theory that makes a higher power, not evolution, responsible for the intricacies of life and the universe. Unlike creationism, which sticks to the literal belief that God created the world in six days, Intelligent Design asserts that the world’s patterns and variety all fit into a master plan.

During the summer of 2005, it seemed as though advocates of Intelligent Design were on a roll in their campaign to earn the theory equal billing alongside evolution in the nation’s classrooms. President Bush himself told Texas reporters at a roundtable in August that “both sides ought to be properly taught,” and school districts in 20 states were weighing the inclusion of ID in their high school curriculums. The newfound legitimacy was the product of long and patient planning.

A 1999 document put out by Intelligent Design proponents drew a 20-year road map for legitimizing and then popularizing their views. Called “The Wedge,” the manifesto mapped out a strategy of inserting Intelligent Design into the cultural conversation by inserting ID adherents into the academy, where they would collect credentials, publish in academic presses, and host academic conferences. “The plan is to draw out real scientists and engage them in debate—all to make it look like ID is part of the debate in the scientific mainstream,” says Barbara Forrest, a professor at Southeastern Louisiana University and author, with Paul Gross, of the 2004 book Creationism’s Trojan Horse: The Wedge of Intelligent Design. Even scientists who appear at conferences to argue against Intelligent Design are later likely to find their names—and their long list of credentials—attached to ID, explains Forrest. “At Baylor, they thought they had it made,” she says. “Here was a school with a fine reputation for science, but it was a Baptist school, so they assumed there would be a welcoming atmosphere for Intelligent Design.”

And so, for William Dembski. Dembski is an outspoken proponent of Intelligent Design. He authored a 2004 book titled The Design Revolution: Answering the Toughest Questions About Intelligent Design and is a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute in Seattle, ID’s mother church. His ascension to the Polanyi Center should have been a textbook case of The Wedge in action. Dembski began referring to his institute as “the first Intelligent Design think tank at a research university.”

The Baylor faculty—especially the scientists whose professional reputations were at stake—was furious. A faculty committee appointed to investigate the suitability of Dembski’s institute pronounced its continued presence unnecessary. In the finest political doublespeak, the review committee graciously allowed that there was a place for Dembski’s theories at Baylor and that the institute could continue to exist—but under a different name, with different leadership and different goals. Dembski would hang on at the school for five more years, courtesy of Baylor’s contractual obligation, but no department would throw him a bone; he didn’t get invited to teach a single class.

In May 2001, things heated up. Baylor’s faculty and its administration clashed publicly over the school’s direction and mission. David Lyle Jeffrey, a literature and humanities professor and onetime provost who acted as Sloan’s lieutenant (though the two did not always agree), proposed an amendment to the faculty’s academic-freedom policy. Until then, Baylor’s policy had mirrored that of the American Association of University Professors, which protects professors’ right to free inquiry and free speech. Jeffrey’s amendment circumscribed that liberty by stipulating that no research or teaching advocating “practices that are inconsistent with Baptist faith or practice” would be permitted at Baylor. Jeffrey says the move was inspired by concerns over accreditation and allocation of teaching resources; it was interpreted by the faculty as an effort to limit truly free intellectual inquiry and impose community standards—standards that even the larger Baptist community, splintered as it was, couldn’t agree on.

On October 27, 2004, Bill Underwood, then a professor at Baylor’s law school, met Jeffrey in a public debate in Bennett Auditorium. More than 300 members of the academic community attended. In an exchange marked by Southern civility, the two professors grappled over where the lines might be drawn between individual rights and communal responsibilities. The perception of President Sloan as a fundamentalist and autocrat made the notion of “communal standards” abhorrent to many—including some who might think differently if the communal standards involved, say, restricting hate speech. The faculty seemed unswayed. In their senate, the professors voted down Jeffrey’s academic-freedom amendment 31-to-0, with one abstention. They also passed a succession of three no-confidence votes on Robert Sloan’s presidency, the last a facultywide referendum where voting took place off campus and was supervised by the local board of elections. Eighty-five percent voted to oust Sloan in May 2004.

“Part of the Baptist code of honor is niceness, so a vote of no confidence is unprecedented,” explained Lynn Tatum, who teaches biblical studies at Baylor. On January 21, 2005, the university’s Board of Regents accepted Sloan’s “resignation” for the sake of healing rifts in the Baylor community and installed Bill Underwood as interim president, effective June l.

The battle was hardly over. The fundamentalists may have lost Baylor, but within Baylor, they would take on not only the tide of history but also the Lone Star individualism of Texas and the democratic fundaments of their own creed.

“THERE IS NO DOGMA MORE PREVALENT within American high culture than that smart people outgrow God,” said Douglas Henry, an assistant professor of philosophy and director of Baylor’s Institute for Faith and Learning. “The more educated, the more erudite, the more discerning and wise one is, the less one is inclined to be a deeply pious Christian, the thinking goes. In higher education, this dogma gets expressed in the axiom that academic excellence and Christian faithfulness are incompatible.”

In any case, Henry said, history has shown that most religious-affiliated schools—Harvard, Princeton, Brown, Yale, etc.—have “renegotiated their identity” and secularized. “If you’re from these schools, you don’t look with pride back to your Congregationalist or Methodist or whatever roots but view them as relics from the past, which thankfully one has been liberated from,” he said. Once, these schools also stood at the crossroads. “ ‘Are we going to opt for faithfulness to our heritage or respectability?’ they asked. And in each of these instances, respectability won and religious roots lost.” Henry, who was appointed to the faculty under Sloan and whose Faith and Learning institute absorbed Dembski’s Polanyi Center over the course of several years as it was being dissolved, believes that Baylor stands at this same crossroads today. “Can the school be a top-tier research university while simultaneously strengthening its Christian roots?” he asked, citing the language in Sloan’s 2012 vision statement. “This is the front line of the challenge. Can Baylor do what history has suggested cannot be done?”

Baylor’s growing pains—and perhaps the nation’s—are intricately linked with the logic behind creationism and Intelligent Design. The thinking goes like this: Evolution, which shows that humans evolved from random mutations over time, implies there were no active, moral choices involved in the progress of man. If humans were created by the random and impersonal forces of biology, chemistry, and environment, then they are not directly responsible for their fate. “This materialist conception of reality eventually infected virtually every area of our culture, from politics and economics to literature and art,” the ID promoters explain in The Wedge. “Materialists denied the existence of objective moral standards, claiming that environment dictates our behavior and beliefs. Such moral relativism was uncritically adopted by much of the social sciences, and it still undergirds much of modern economics, political science, psychology, and sociology.” The Wedge links these ideas to the modern conservative agenda: “Materialists also undermined personal responsibility by asserting that human thoughts and behaviors are dictated by our biology and environment. The results can be seen in modern approaches to criminal justice, product liability, and welfare. In the materialist scheme of things, everyone is a victim and no one can be held accountable for his or her actions.”

This reasoning differs considerably from the old William Jennings Bryan worry that evolution simply disproved the existence of God. Today, the antievolutionists take an extra tack: Evolutionary randomness equals moral relativism equals the postmodern me-first culture of hedonism. “Hedonism” is manifest politically by those who defend welfare for the irresponsible, abortion rights for the irresponsible, prison reform for the irresponsible, malpractice settlements for the irresponsible consumer, etc. Ironically, the fundamentalist call to societal responsibility can sound a lot like liberal “It takes a village” nostrums and appear an affront to winner-take-all capitalism.

In Baylor’s case, this critique of the me-first culture meshed with the dustup over academic freedom. “Partly what’s going on in this debate is the question of whether individualism, characteristically a Texas virtue, will be practiced to the disadvantage of the common good,” David Lyle Jeffrey told me. The week Underwood assumed the presidency, Jeffrey was demoted from provost to ordinary professor. He says he is happy to be back teaching Christian biblical tradition in Western literature. With his graying hair, less-than-crisp jacket, and book-lined office, he seems the consummate professor: a thoughtful and articulate advocate who enjoys a battle of wits. He admits to being more “communitarian” than many of his Texas Baptist brethren: “We need to have a conversation to find out how to make a place for accountability to the common good—while preserving academic freedom. Some of my colleagues, like Bill Underwood, might say that individual freedom ought to define who we are as Baptists,” he said. “I, who am by local standards not a very good Baptist, would say no man is an island.”

In May 2004, Jeffrey argued these points in a speech at Wheaton College; his language there continues to trouble some colleagues. He decried Baylor’s faculty-hiring practices for being “too little concerned with articulate faith,” complaining that “even among more faithful faculty, biblical literacy and theological competence is at a far lower ebb than might have been found a generation ago amongst rural Baptists and other evangelicals who never saw the inside of a college classroom.” As reported in the Baptist Standard, Jeffrey blamed the lapse on “anarchic, postmodern advocacy—or radical subjectivism” in higher education, which “drowns all music but its own.” Further, “in their attempt to elevate the individual over community, postmodern educations…have resisted ever more strongly the privilege of counterbalance—of communal freedom to speak collectively—especially for religious or dissenting communities to define a communal rather than merely individualistic right to First Amendment privilege.”

For Christian intellectuals, including many at Baylor, these ideas are wedged into the cultural conversation in subtler, more palatable forms that are harder to argue with. Scholars here mix and match language and arguments, nestling the apostle Paul into a sentence next to Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jesus into bed with Jefferson, the apocalypse spooning with global warming. The liberal politics of oppression is invoked in defense of Christian scholars, and the Western white men who wrote the canon are recast as the marginalized. “In postmodernism, every perspective has a seat at the table—except Christian perspectives,” Henry insisted to me. “So you can pull up a chair at the postmodern academic table as a Marxist economist, or a queer-studies theorist, or a politically liberal legal scholar, or a Hindu or Jewish person or Muslim—but the idea of pulling up a chair with a Christian perspective is excluded.” Henry acknowledges that historically, Christians essentially hosted this ivory tower dinner party, invited the guests, and led the conversation. “But there is a turnabout-is-fair-play ethos at work now,” he said, “that is not very academically or intellectually respectable. Any self-respecting university would want to be a place where truth can be arrived at with an open exchange of ideas, and that means giving everybody a shot.” He cited James McClendon’s 2000 book, Witness, which says that Christian universities are engaged in a tournament of narratives about the nature of reality. These “metanarratives” are vital to the cultural conversation. “The Christian university has to be willing to participate in the tournament, to clad its armor, pick up its lance, and joust.”

The problem is that even among Baptist intellectuals, like those at Baylor, there is no agreement about just what this metanarrative ought to be. Baptists honor the “priesthood of the believer,” which means the worshippers are charged with reading and interpreting the Scriptures for themselves, unlike, say, Catholics, for whom the priest serves as an intermediary between the worshipper and God. There is no church hierarchy and no particular creed Baptists must follow, in theory. For these reasons, Southern Baptists see theirs as a particularly democratic faith. Baptists espouse something called “soul competency,” the belief that each person is capable of reading and interpreting the Scriptures for himself. The rub is: Doesn’t this come uncomfortably close to being a synonym for individualism?

In the last decade, Southern Baptists have been fighting over whether it is a “priesthood of the believer” or “priesthood of believers.” At stake in the pluralizing “s” is whether a Baptist governing body—or community of Baptists—is charged with guiding individuals in the practice and interpretation of faith. The more conservative Southern Baptists, who also believe in the literalism of the Scriptures, think some Baptist community standards are essential. The Baptist Cooperative Fellowship, a group that splintered from the Southern Baptists in 1991, thinks otherwise.

But this central concern, combined with an evangelical mission, poses three big problems. On a personal level, if a Baptist is to act on his faith, or convictions, can he do it without imposing his interpretation of the Scriptures on others—or should he? On an organizational level, Baptists who are not “creedal” do have several organizing bodies that issue proscriptive documents like the 1963 “Faith and Message,” which came out of that year’s Southern Baptist Convention. Vehement disagreements over these documents—especially the 1991 statement that reinforced wives’ obligation to do as their husbands tell them with Christian humility, denounced women preachers, and came down hard against homosexuality—have created multiple schisms. Finally, on a political level, Baptists are torn between honoring a personal interpretation of faith and a bold desire to impose their own beliefs on others—and on the nation.

AS STUDENTS LANGUIDLY strolled past his window in the 99-degree heat during the first week of Baylor’s fall classes, Bill Underwood’s musings about how one integrates faith and learning brought him to a rumination on the musical tastes of his own adolescent son. Sometimes the boy listens to Christian rock, like Switchfoot, that has overtly Christian themes; sometimes he listens to U2, a mainstream band whose members happen to be Christian. “Similarly,” Underwood said, “in academia you have Christian scholarship that focuses on examining issues from an overtly Christian perspective and you have mainstream scholarship by scholars who are Christians. The way I see it, we ought to be preparing students for life in a mainstream world, and that requires exposure to and education in mainstream disciplines and examining those disciplines from mainstream perspectives,” he said. “There is no such thing as Christian accounting or Christian chemistry. When filing a suit, there’s no such thing as a Christian venue.”

That said, he thinks Baylor’s mission actually gives him more liberty in the classroom through the chance to offer the occasional religious insight. “Unlike state-sponsored schools, we have the freedom to examine issues from an overtly Christian perspective when relevant,” he said. “When I talk about the death penalty, I have the freedom to examine the teachings of Christ, which I think are incompatible with the death penalty—and that provides an educational dimension that we offer here that isn’t available at a lot of places.”

The same moral consideration applies to other issues—like gay rights—that unsettle the old guard, he said, referring to the fury Baylor’s ex-president unleashed on the student newspaper last year when its editors came out in support of gay marriage. Underwood is a free-speecher in the Oliver Wendell Holmes tradition, and he gave the old jurist a nod: “A free marketplace of ideas can be very threatening to some.”

Underwood does not consider true Baptist doctrine to be at odds with his own ideas; his reign at Baylor draws heavily on the tenets of soul competency. “Because of the historic Baptist commitment to individual freedom of thought,” Underwood insisted, “a university sponsored by Baptists ought to have the freest of academic environments.”