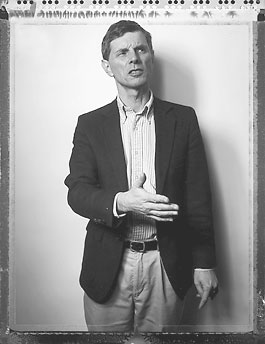

Photo: Henry Leutwyler

DR. DAVID GRAHAM IS LOSING WEIGHT AGAIN. His wife noticed first, then his colleagues at the Food and Drug Administration. Graham is a skinny man, and when he drops weight, his cheekbones seem to sit higher on his face. His striped cotton shirts, the frumpy uniform of a government scientist, hang more loosely on his narrow frame. But he isn’t eating, and no wonder: Graham, the scientist who brought the Vioxx scandal to the nation’s attention, feels like a marked man.

“I’m no longer welcome,” he says, sitting in a Rockville, Maryland, coffee shop in early February. He has just left another frustrating day at work, where his boss warned him not to disclose new safety findings about a popular class of painkillers called Cox-2 inhibitors. In a few minutes, he is due at his son’s Boy Scout meeting, but all he can talk about now is the exhaustion of working in a drug-safety system in turmoil. “I’m hoping things will calm down, but I don’t think the FDA will let that happen,” he says. “How do you get off the merry-go-round?”

In August 2004, Graham told his supervisors that, in light of his research, high-dose prescriptions of the painkiller Vioxx, which appeared to triple heart attack rates, should be banned. They told him to be quiet. Their reasoning was circular: That’s not the FDA’s position; you work here; it can’t be yours. Dr. John Jenkins, the FDA director of new drugs, argued that because Graham’s findings didn’t replicate the drug’s warning label, Graham shouldn’t be raising the warning. Another supervisor, Anne Trontrell, called Graham’s position “particularly problematic since FDA funded this study.” Days after Graham’s pronouncement, the agency approved Vioxx for use in children.

But Graham was right. The following month, Merck pulled Vioxx from the market after its own research found that the drug, even when taken at low dosages, doubled the risk of heart attack. The announcement provided Graham no vindication. With a scandal on the horizon, the FDA brass now saw him as a danger. They couldn’t silence the message, so they tried to take out the messenger.

Dr. Steven K. Galson, the acting director of the drug-evaluation division at the FDA, told reporters that Graham’s work “constitutes junk science.” Then he sent an email to an editor at the prestigious British medical journal The Lancet, questioning the “integrity” of Graham’s data—a suspicion that proved baseless. The FDA’s acting commissioner, Dr. Lester Crawford, criticized Graham for evading the agency’s “long-established peer review and clearance process.” Another official made calls to at least one Senate staffer, disparaging Graham personally and professionally.

Eventually, he was heard. In November he went before the Senate Finance Committee hearing on Vioxx. Gaunt (he’d lost 12 pounds over three months) but very lucid, Graham took his place before a bank of cameras, wearing his only sport coat, a 20-year-old blue blazer with brass buttons. He explained his conclusion that patients taking high doses of Vioxx were suffering heart attacks. “The estimates range from 88,000 to 139,000 Americans,” he said. “Of these, 30 to 40 percent probably died. For the survivors, their lives were changed forever.” According to the top end of those projections, the toll Vioxx had already taken was comparable to the number of Americans killed in Vietnam. “The FDA, as currently configured,” Graham told the committee, “is incapable of protecting America against another Vioxx. We are virtually defenseless.”

But three months later, as Graham sips iced tea in a Rockville cafe, the FDA is again trying to suppress his research, this time on the effects of pain medications similar to Vioxx. “I think we’ve already articulated our preference,” his supervisor, Dr. Paul Seligman, wrote him in a terse email. The agency doesn’t want Graham presenting his latest research to scientists who will be meeting in a few days to discuss the drugs.

David Graham is headstrong, but not insubordinate. He cannot afford to lose his job. His family has just moved to a new house. His wife, Nancy, stopped working as a lawyer so she could homeschool their six children. Really, though, he has no more time to sit here worrying. The Boy Scouts are competing for their merit badges this evening. He finishes his iced tea.

“I’ve made a commitment,” he says, before walking out the door. “I’ll weigh myself this evening.”

WE LIVE IN THE pharmaceutical era of medicine, a time of tablet-sized miracles and blockbuster serums. More than 70 new drugs are approved every year, adding to the thousands for which American doctors already write some 3 billion annual prescriptions. The medications prolong countless lives and cause millions of harmful side effects. For most patients, the benefits far outweigh the dangers. An aging man will risk diarrhea to restore his virility. A cancer patient will lose her hair in the hope that chemotherapy will save her life. FDA safety officers like Graham spend their lives searching out the other type of pills, the unexpected killers that harm patients after the FDA has approved them.

Since 1988, Graham has called for the removal of 12 drugs from pharmacy shelves, leading to 10 recalls that have likely saved hundreds, if not thousands, of lives. Each recall is an embarrassment for Graham’s employer, the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, which approved the drugs in the first place. The trouble is that the roughly 2,300 staffers who support the approval process, and the 109, like Graham, who study the safety of drugs after their release, all fall under the same leadership, and that leadership is highly responsive to industry. In recent years, nearly half of the center’s $400 million budget has been paid for by drug companies. This arrangement stems from a 1992 agreement, made partly at the urging of AIDS activists, that the FDA would speed up approvals in exchange for “user fees” from industry. “The focus at FDA is efficacy,” says Dr. Curt Furberg, a scientist at Wake Forest University who advises the agency. “Safety is a stepchild.”

For the pharmaceutical companies the system works just fine. “The drug-approval process [in the United States] is second to none,” says Jeff Trewhitt, a spokesman for PHRMA, the drug industry’s trade group. “This is an exhaustive process.”

Companies eventually recall about 3 percent of their drugs for safety reasons. Behind many of these recalls are scientists like Graham, who often find themselves pitted against their own supervisors. “If you say something negative about a drug, they try to shut you up,” says Dr. Sidney Wolfe, an FDA watchdog for the group Public Citizen, which has been exposing dangerous drugs for three decades. “David is not the only one, by any means, who has raised issues that later proved to be correct.”

In 1998, for instance, an FDA drug reviewer named Dr. Robert Misbin wrote a paper showing that the diabetes drug Rezulin had caused liver failure in a patient during a controlled study. When his bosses tried to prevent him from publishing, Misbin saw firsthand how the system encouraged the sacrifice of public health to the interests of the industry. “One of my supervisors said something to me that I have never forgotten,” Misbin says, “that we have to maintain good relations with the drug companies because they are our customers.” Misbin eventually went public with his concerns, and the drug was pulled a year later. But he has paid for sticking to his principles. “I am no longer given any good projects,” he says.

Dr. Andrew Mosholder, another FDA reviewer, faced similar pressures last year when he completed a study showing that antidepressants increased suicidal behavior in children. Further studies proved that Mosholder’s science was spot on. But his bosses told him not to report the findings. When someone with access to the study passed his results to the press, the FDA launched an investigation into the leak. According to Tom Devine at the Government Accountability Project, who later became Graham’s lawyer, several scientists were interrogated and threatened with possible jail time.

Such intimidation has worked. In 2002, about one in five FDA scientists told federal investigators that they felt pressure to approve drugs despite reservations about safety and efficacy. Two-thirds said they lacked confidence that the agency adequately monitors drug safety after approval.

DAVID GRAHAM IS A CHILD of the Bronx. One of six children, he spent his teenage years in a cramped home in northern New Jersey, sleeping three to a room. It wasn’t until he reached college, at Franklin & Marshall, that he decided to become a doctor. Johns Hopkins Medical School offered him a chance at early admission, and he accepted. His plan was to become a general practitioner in Vermont, where he’d live with Nancy Peterson, a girl he had met in the freshman dormitory. He graduated from med school with the second-highest grades in his class–not the highest, he points out, owing to a single B in the medical history course he cut every other Friday, when he’d ride a bus 75 miles to spend the weekend with Nancy. She married him a year later. “It was worth it,” he says.

Hopkins, however, was geared toward academic research, not producing family doctors for the Green Mountain State. And Graham never took to working with patients anyway. “What I really enjoyed was problem solving,” he says. So after residencies in internal medicine at Yale and neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Graham took a job at the FDA in epidemiology. His first major safety review, in 1988, focused on a pill called Accutane, intended for patients with severe, previously untreatable acne. The study proved to be a crash course in the ways of the FDA.

At the time, Accutane was seen as a miracle cure by people just like Graham, who still bears the scars of teenage acne. But the side effects could be horrible. One in four children born to women who got pregnant while using the medication suffered from birth defects. Many women didn’t bring their babies to term at all, losing them to miscarriage, and most pregnancies ended in abortion. Graham looked at the data and sounded an alarm. Attempts to educate young women about Accutane’s risks were failing. “Only the immediate withdrawal of Accutane from the market will work,” he wrote to his supervisors in 1990. “The delay only compounds the body count.”

That statement was both scientific and political. Graham is opposed to abortion, and the bodies he was referring to were those of the thousands of unborn children whose mothers had taken the drug. Devoutly Catholic, Graham keeps a postcard image of Jesus on his office wall and speaks easily about his calling to service as a Christian. He taught himself ancient Greek so he could read the New Testament as it was written. For him, the scientific process is an extension of his faith. “He really does believe that to know what is real is to know something about the Author of the truth,” says John Cavanaugh-O’Keefe, a pro-life activist who met Graham at a prayer group.

But for his managers at the FDA, under pressure from dermatologists and Roche, the drug’s manufacturer, Graham’s religion was an irrational excuse for his unreasonable claims. “They’d call him the right-to-life nut,” says Rep. Bart Stupak (D-Mich.), who recently introduced legislation to restrict patient access to Accutane. “But everything he said has pretty much been proven.”

The FDA sided with Roche, rejecting Graham’s calls to withdraw the drug and his later pleas to restrict its distribution. In the years that followed, the drug’s use among young women nearly tripled, and Roche’s annual Accutane revenues exceeded $1 billion. The company designed a voluntary program to encourage birth control among users, but the number of pregnancies continued to rise. Nonetheless, Roche described the program as a success, noting that occasional pregnancies were the inevitable result of birth-control failures. “You can’t control everything when you are dealing with human behavior,” explains Gail Safian, a Roche spokeswoman.

In 2002, when Roche’s patent expired, the FDA helped create a stricter program to ensure that women on the drug used birth control, requiring monthly proof of a negative pregnancy test. Two years later, a panel of scientists found the system was still failing. In November, as the FDA was attacking Graham for his work on Vioxx, the agency announced still stronger restrictions. These measures echo changes Graham asked for more than a decade ago.

SHORTLY AFTER Merck pulled Vioxx from the market last September, Graham began carrying an index card full of phone numbers in his breast pocket. The little scribbles of red and black ink were his lifelines, contacts to a dozen supportive congressional staffers and reporters who’d sought him out after he went public. It had become clear that he wouldn’t survive long in his job without help from some heavyweight defenders.

Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley, the Republican chairman of the Finance Committee, became his primary protector. “It’s people like this who give us the opportunity to know that something is wrong, helping me do my job,” Grassley says. He believes the industry has far too much influence on FDA deliberations over safety. “There should only be one chair at the table,” he says, “and that is for the American people.”

The only way to resolve the FDA’s dangerous conflict of interest, according to Graham, is to create an independent center for drug safety, situated on one side of a fire wall; those who study efficacy and recommend approvals would be on the other side. Researchers would report their findings to scientists with no stake in the performance of the drug. But this is a more drastic change than the agency is likely to implement of its own accord. The FDA has made other gestures: It has announced a new committee to monitor safety issues, asked for an investigation of its procedures by the Institute of Medicine, and proposed reassigning about 20 scientists to work on drug safety.

Jeff Trewhitt, the spokesman for PHRMA, rejects Graham’s solution out of hand. “He seems to start from the premise that the drug-safety program is broken, and we don’t accept that premise at all,” Trewhitt says, adding that any new regulation “could mean slower delivery of new medicines to patients.” That view has also been embraced by the White House, which maintains close ties to the drug industry and its more than 600 lobbyists. During a television interview, Andy Card, chief of staff to President Bush, said that the administration’s handling of the Vioxx recall was “a testament to the FDA and how they do their job.”

This leaves the prospect of real systemic change at the FDA in the hands of Congress. Indeed, throughout history, safety scandals have regularly sparked congressional action. The agency itself was established by Congress in 1906 after a wave of adulterated or dangerous drugs was exposed in the press, including a “headache powder” containing acetanilide that caused heart attacks. In 1962, Congress began forcing pharmaceutical companies to test drugs after doctors distributed doses of a pill called thalidomide to pregnant mothers, a sedative later shown to cause birth defects.

But the scale of the Vioxx scandal appears, in sheer numbers, far greater than any other in the nation’s history, and Congress has yet to respond. Not only has the drug been widely used—peaking in 2001 at 25 million prescriptions—but it has increased by two- or threefold the risk of one of the most common causes of death, heart attack.

IN FEBRUARY, six months after the Vioxx scandal broke, Graham still finds himself struggling to get the word out. His latest research, based on the records of 651,000 California Medicaid patients, raises safety concerns about other drugs in the same class as Vioxx. Mobic, a popular painkiller still viewed as safe, appears to be increasing heart attack rates by about 37 percent. Celebrex, a blockbuster pain medication from Pfizer, increases rates by about 25 percent in high doses. Although the findings are not statistically conclusive, the study adds key data to the medical literature. But Graham’s superiors aren’t interested. The email Graham receives before heading to his son’s Boy Scout meeting asks him to focus only on “the key studies in the published literature.” According to Graham, he can present only one unpublished study, a report paid for by Merck.

Graham’s most powerful defender comes to his aid: Senator Grassley sends a terse letter to the acting FDA commissioner, Lester Crawford, demanding an explanation of why Graham can’t present his data. Grassley gives Crawford a deadline for responding: February 16, opening day of the three-day FDA advisory committee meeting.

The gathering is held in an overstuffed Hilton conference room in Gaithersburg, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C., covered with rolling parking lots and B-rated shopping malls. Broadcast trucks ring the hotel, and the hallways are crowded with cameras. Just hours before Steven Galson, Graham’s supervisor, is to welcome the 32 scientists assembled from around the country, Crawford intervenes. The backtracking is brazen. “It goes without saying,” Galson says in his opening remarks, “that all FDA staff are free to make any presentation without fear of any retaliation.” Graham, who is scheduled to speak the next day, leaves the meeting to hastily redesign his presentation.

When he returns the following day, he’s wearing the same coat and the same tie. In the previous three weeks, he has lost two more pounds. “I’d like to take this moment to thank Dr. Crawford for his leadership, for making it possible for me to present our preliminary data from a study from California Medicaid,” he tells the gathered scientists. He presents his findings on the dangers of Mobic and Celebrex in high doses. About Vioxx, he says the risks associated with taking high doses are “probably more significant than smoking or diabetes or hypertension.” Then he challenges the FDA to begin shifting its assumptions when it considers a new drug. “Let’s start out at the beginning assuming the drug isn’t safe.”

On the third day of the conference, Graham dips outside the meeting room for a break and is immediately surrounded by a scrum of reporters. The committee of 32 scientists was nearly unanimous in acknowledging the dangers Graham presented to the FDA six months earlier. But they voted by a narrow margin to keep the two most troublesome painkillers, Vioxx and Bextra, on the market, calling instead for tighter restrictions on distribution. Ten of the scientists were consultants for the manufacturers of the drugs in question. Had they not been allowed to vote, according to an analysis by the Center for Science in the Public Interest, both Vioxx and Bextra would have been recalled.

The reporters ask Graham for his reaction. “The fact is, debate is happening,” he says. It may be one of the last times he finds himself in the public spotlight as a federal researcher. If the experience of others is repeated, he’ll be sidelined within the agency and denied any meaningful projects over the coming year. Despite Grassley’s backing, he expects to be pushed out of his job. Standing outside the conference, however, Graham still has the power to speak out—and infuriate his government employer. “Sunlight is the best disinfectant,” he tells the surrounding crowd. “This is more sunlight on the problem.”