A dark cloud cast a chill over our cozy liberal hearth a few months back. Four-and-a-half-year-old Dashiell and his 9-year-old sister, Nadja, were watching cartoons on TV while we parents sat self-exiled in the living room. Suddenly Nadja raced in, flushed, dragging her little brother by the hand, insisting that he repeat the comment he’d just made to her during the commercials. Bewildered by the fuss she was making, he was prodded into mumbling: “I jus’ said I din’t like black people.”

Françoise and I exchanged glances. I gulped, bracing myself for yet another Difficult Parenting Moment while Françoise, unfazed, simply reminded Dash of Robert, the extraordinarily gifted teacher at his preschool, and a couple of black playmates. He conceded that he liked them fine, but still innocently elaborated that black people weren’t as good or pretty as us, somehow dissociating the people he knew from the idea of blackness. Rallying, I launched into a lecture about the danger of judging people as a group and about the tribal fear of otherness, illustrated with a quick gloss of my own parents’ experiences as Jews in Hitler’s Europe (using a Dr. Seuss-approved, 225-word vocabulary) and I capped it all with some G-rated variant of the old rhetorical question: “Who would you kick out of bed: Lena Horne or Kate Smith?” When the dust settled, Dash seemed contrite, though restless, and the kids adjourned back to their cartoon show.

Now, whether Nadja was motivated by sibling rivalry, knowing that her brother’s passing comment wouldn’t play well, or by a genuine sense of moral outrage (she has always been an exceptionally empathic kid), or — most likely — by a combination of the two is beside the point: I’m trying to dive into my own psyche’s deep water here, and only by extension my kids’ and America’s. Françoise seemed mildly amused by the incident; having grown up in France, she is remarkably colorblind about American race matters (though she has her own culturally manufactured demons to ward off when North African Muslims are the issue).

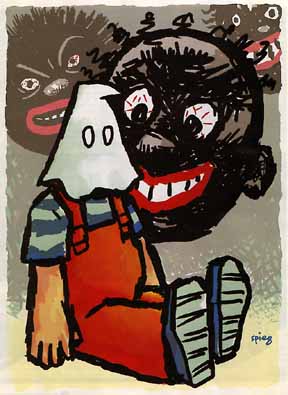

I was left deeply discomfited, guilt and muck oozing to the surface. How did this racist virus get to flit through Dash’s head in our nobly intentioned peaceable kingdom? To what degree am I the direct carrier? The kids are both relatively unexposed to mass culture (despite this anecdote’s implication, they log in well less than three hours a week of rather supervised television time), and both are enrolled in New York’s very ethnically diverse United Nations International School. In fact, the first public figure I ever heard Dash refer to was Martin Luther King Jr., although it’s true that his actual reference was to Arthur Luther King and the knights of the Round Table. I cursed myself for once unthinkingly taking him to a screening of the 1932 Tarzan, the Ape Man; it was billed as a kiddie matinee, but the colonialist wet dream of a white jungle god among the subhuman savages left me unhinged and clearly made a strong impression on my son, who has fantasized ever since that he is being raised by apes.

Far more egregious, of course, is the raw truth that we have very few black people in the insular world of our intimate circle. There are a few co-workers at Françoise’s office, a few writers and editors I’m glad to see at parties and wish I saw more often, and, um, Pearl, the woman who cleans our house once a week. In fact, I haven’t actually had a black friend I spent much time with since around 1964, when I was in high school. In that golden age one of my cafeteria tablemates, Ronnie Hamilton, and I shared the dream of becoming cartoonists. He could draw serviceably well but had trouble with gags. When he started a weekly strip, “Super Colored Guy,” for a small Harlem newspaper, I ghostwrote it for him under the pen name Artie X.

We remained pals until sometime after my namesake, Malcolm X, was murdered in 1965. During the several decades that followed I felt that a wall had somehow gone up that kept all but the most committed “white negroes” from commingling with the black ones. Though I sense that this invisible barrier is no longer as firmly in place among us intelligentsia types, it remains true that — perhaps only through the luck of the draw — none of my closest friends are black.

Was Dash’s comment somehow provoked by cultural osmosis or by my own inner racist? While fretting over this I somehow unearthed a genuine repressed memory: I once actually called somebody a nigger. A nigger! I suppose that since I couldn’t reconcile this behavior with my self-image, I had buried the incident.

It was 1968. I had been registered in an upstate New York college, avoiding the draft and taking LSD as casually as some of my contemporaries now drop antacids. One day something snapped and I woke up in restraint sheets in a state mental hospital. I wasn’t sure who or where I was. I was neither male nor female, neither young nor old, neither black nor white. I was, as Popeye or Jehovah might have put it, what I was, and that’s all that I was.

After several days of being fed glucose intravenously I’d recovered enough to be out of a padded cell and in a simple hospital room. When I had to go to the toilet in the middle of the night I discovered that my door was kept locked, and I had to bang on it repeatedly before a large, sleepy black man dressed in white unlocked the door and escorted me to the toilet. I remember getting fascinated by the bathroom tile pattern and being hustled along back to my cell by my guard. A very short time later I had to piss again. Repeated banging got the night man back a second time. Unfortunately, when my glucose diet required yet a third trip to the bathroom, the night man wouldn’t answer my knocks and calls, which grew ever more urgent as my bladder swelled. When he eventually got to the other side of the metal door he just growled, “Shut up! You’ll wake up the other patients!”

I pleaded. I cursed. I screamed, but to no avail. He was adamant in insisting that I just wait until morning. I had no choice and pissed through the narrow crack at the bottom of the door. I trembled with anger and shame at being reduced to such powerlessness. I wanted some further revenge. And it is then that I must have remembered that I was white and he wasn’t. I heard him muttering and mopping up my urine. “Clean it up, nigger!” I screamed. He unlocked the door, punched me in the stomach hard, and slammed the door shut. When I was able to breathe again I stood by the door and shouted it over and over: “Nigger! Nigger! Nigger!”

Looking back at that moment nearly 30 years later, it’s sobering to know that even in my addled state I was able to locate the weapon that could humiliate that jerk so effectively. A couple of months after I was released from the mental hospital, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. I took no responsibility for it; I was crazy, but not that crazy!

Art Spiegelman is the author of Maus (Pantheon, 1986).