Editor’s Note: Nearly three decades ago, this profile by David Osborne offered the definitive portrait of the future Speaker of the House as a young man. As his first ex-wife later put it, Mother Jones “scooped the world on Newt Gingrich.” The article revealed sides of Gingrich that continue to dog him to this day: the reports of infidelity, the now-infamous story of his hospital-room visit with his first wife, and a mile-long trail of aggrieved colleagues. Gingrich later called the article’s publication “one of the saddest things in my public career.” Also: Read our guide to Newt’s 33 years of overheated rhetoric and see 27 years worth of Newt illustrations in the pages of Mother Jones.

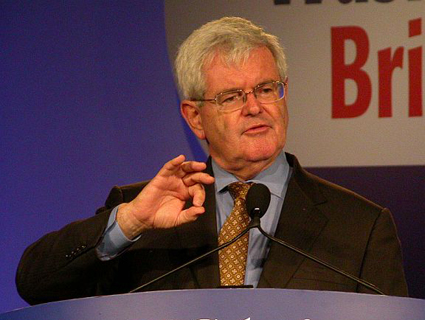

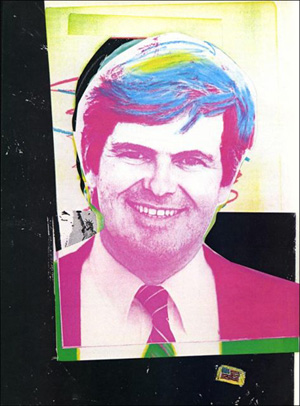

The original illustration from the November 1984 issue of Mother Jones. Illustration: Rudy Vanderlans

The original illustration from the November 1984 issue of Mother Jones. Illustration: Rudy Vanderlans

Last May, US Representative Newt Gingrich stood in the well of the House to rebut charges made by Speaker Tip O’Neill. For months, Gingrich had been harassing the Democrats in evening speeches broadcast over C-Span, the cable channel that carries House sessions. He called them “blind to communism”; he threatened to “file charges” against ten Democrats for a letter they wrote to Nicaraguan leader Daniel Ortega; he accused one Democrat of placing “communist propaganda” in the Speaker’s lobby. In retaliation, O’Neill ordered the C-Span cameras to sweep the floor every few minutes to show the world that Gingrich and friends were declaiming before empty seats. And on May 14, he attacked Gingrich for questioning the patriotism of members of Congress.

Now the showdown was at hand. The chamber was full, the hubbub audible. Cocksure and articulate, Gingrich repeated his attack on Democratic foreign policy. O’Neill’s words, he said, came “all too close to resembling a McCarthyism of the Left.” He had accused no one of being un-American, he insisted: “It is perfectly American to be wrong.” When Democrats rose to challenge him, he deflected their criticisms, ignored the tough questions, pounced on the easy ones, and demonstrated all the techniques of a master debater.

Finally O’Neill took the floor, repeatedly interrupting Gingrich. Back and forth they went, the brash young Republican from Georgia and the indignant white-maned Democrat from Massachusetts. “My personal opinion is this,” O’Neill roared at last, shaking his finger at Gingrich. “You deliberately stood in that well before an empty House, and challenged these people, and challenged their patriotism, and it is the lowest thing that I’ve ever seen in my 32 years in Congress.”

Immediately, Minority Whip Trent Lott rose and asked that the Speaker’s words be ruled out of order and stricken from the record. In the House, normally a bastion of civility, members are forbidden from making personal attacks on one another. After five minutes of nervous consultation, the chair ruled in Lott’s favor. That night, the confrontation between Gingrich and O’Neill made all three network news programs. The third-term Republican from Georgia had arrived.

Confrontation is not new to Gingrich, and the battle with O’Neill was no accident. Before interviewing Gingrich for this story, I watched him give a speech to a group of conservative activists. “The number one fact about the news media,” he told them, “is they love fights.” For months, he explained, he had been giving “organized, systematic, researched, one-hour lectures. Did CBS rush in and ask if they could tape one of my one-hour lectures? No. But the minute Tip O’Neill attacked me, he and I got 90 seconds at the close of all three network news shows. You have to give them confrontations. When you give them confrontations, you get attention; when you get attention, you can educate.”

Nor is it an accident that Gingrich has since emerged in the media’s eyes as a rising star of the conservative movement. In his six years in the House, the 41-year-old former history professor has virtually ignored the traditional goals of a young member of Congress: authoring legislation and steering it through to passage. Instead, Gingrich has concentrated on building a movement capable of remaking the Republican party. In the process, he has created a disciplined band of Young Turks loyal to his leadership, forged a new conservative ideology for the post-Reagan years, and forced his party’s leaders—long content to go along and get along in a House dominated by Democrats—into a more combative stance. This summer, he, along with presidential prospect Jack Kemp, led the successful Republican platform fight that symbolized the ascendancy of the hard Right within the party.

Gingrich combines qualities rarely found in one politician: He is a brilliant speaker and debater, he is an effective guerrilla on the House floor, and he is a genuine political strategist and theorist, who by the force of his ideas has begun to reshape Republican politics. David Broder of The Washington Post, the dean of political columnists, touted him several years ago as one of America’s future leaders. Richard Viguerie, leader of the New Right, told me he considered Gingrich “the single most important conservative in the House of Representatives.” Gingrich’s ideology is an unusual blend of hard-right conservatism on economic issues, foreign policy, and the family, tempered by moderation on civil rights, women’s rights, and the environment. What stands out as particularly unique, however, is his fascination with “the future.” Quoting futurists such as Alvin Toffler (The Third Wave) and John Naisbitt (Megatrends), Gingrich believes we are at the dawn of an entirely new era, a leap forward akin to the industrial revolution. His goal is to fashion a political ideology relevant to that future, an ideology capable of creating a new American majority. “I see myself,” he explained, “as representing the conservative wing of the postindustrial society.”

Gingrich has coined a slogan to communicate his vision: a “conservative opportunity society”—the opposite, at least in language, of the liberal welfare state. Its three pillars are free enterprise, high technology, and traditional values. But unlike the Republicans of the past 50 years, Gingrich is not content simply to object to every liberal spending program; he seeks to develop a new, positive agenda for the nation. He is not antigovernment, but antiliberal. “I believe in a lean bureaucracy, not in no bureaucracy,” he said. “You can have an active, aggressive, conservative state which does not in fact have a large centralized bureaucracy…This goes back to Teddy Roosevelt. We have not seen an activist conservative presidency since TR.”

In many ways, Gingrich is an unabashed probusiness, anticommunist, Moral Majority version of Gary Hart. “The opportunity society,” he predicts, “will answer the cries of the baby-boom generation for a new politics responsive to the future’s needs.”

There is a problem here, of course. Baby boomers generally distrust the anti-Equal Rights Amendment, antiabortion, anticommunist politics of the Bible and flag. Gingrich seeks to blur some of these distinctions. He works closely with the Moral Majority, but at times votes against its positions, or is absent on key votes. He opposes the ERA, but maintains that he would support an ERA amended to keep women out of combat, protect noncoed schools, and so on. At bottom, however, he believes that the cultural rebellion of the baby boomers has run its course. Today’s crisis is “a culture in dissolution”: teen-age pregnancy, child pornography, and rampant crime. “I would argue that you can make a very effective traditional values pitch that child pornography is obscene, and that those people ought to be thrown in jail. Most of my baby-boom friends, when they were 18, would have argued intellectually at the coffee house that people ought to be allowed to do what they want to. Now that they’re 37 and they have six-year-olds, they’re real tough on child pornography.

“I can carry the baby boomers,” Gingrich boasts. “I could kill Gary Hart in that group, on those issues.”

For many who have encountered Gingrich, this is intriguing stuff. His politics clearly hold potential-if not the “opportunity to seize the baby boomers for a lifetime” that he claims, at least the chance to siphon away a portion of the Hart vote. To look into that potential, and to discover more about this new-age Republican, I journeyed to Georgia, whence he hails.

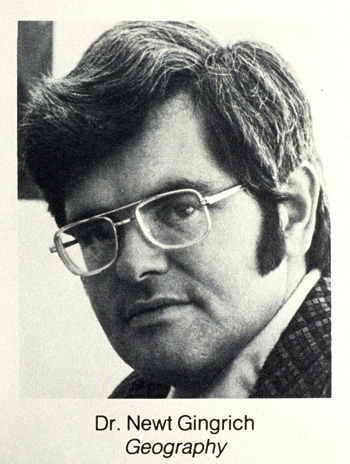

A sideburned Newt Gingrich as geography professor at West Georgia College, Carrollton, GA circa 1975. Robin Nelson/ZumaThe Sixth Congressional District, which stretches from the suburbs south of Atlanta into rural west Georgia, fits Gingrich perfectly: It is booming, middle class, and economically revolves around the high-tech Atlanta airport, which vies with Chicago’s O’Hare as the world’s busiest. This is the New South, where spanking new highways crisscross the countryside, shopping centers seem to sprout up overnight, and the sparkle of new restaurants, new businesses and new homes is everywhere. This is the future.

A sideburned Newt Gingrich as geography professor at West Georgia College, Carrollton, GA circa 1975. Robin Nelson/ZumaThe Sixth Congressional District, which stretches from the suburbs south of Atlanta into rural west Georgia, fits Gingrich perfectly: It is booming, middle class, and economically revolves around the high-tech Atlanta airport, which vies with Chicago’s O’Hare as the world’s busiest. This is the New South, where spanking new highways crisscross the countryside, shopping centers seem to sprout up overnight, and the sparkle of new restaurants, new businesses and new homes is everywhere. This is the future.

The district may be tailor-made for Gingrich, but I was unprepared for what I found in Carrollton, the prosperous west Georgia town where he launched his bid for Congress. I expected great pride in a native son; instead, I found great bitterness. To many of his former supporters, Newt Gingrich is not the cutting-edge politician one sees in Washington. He is a man who campaigned on themes of ethics and morality, then betrayed his words; a candidate who speaks constantly of restoring traditional values, but whose private life tells a very different story.

“I will do everything I can to make it possible for the public to hear the whole truth about my record and my beliefs,” Gingrich proudly declared in 1974. In that spirit I set out to discover what was behind the bitterness in Carrollton.

Newt Gingrich arrived in Carrollton in 1970, fresh out of graduate school but already a veteran of two political campaigns. Gingrich likes to tell the story of his “calling” to politics. At 15, while in France where his stepfather was stationed, he visited Verdun, where hundreds of thousands of French and German soldiers died in World War I. He stared at the immense pile of bones that could not be identified after the battle, recoiling in horror. “I left that battlefield convinced that men do horrible things to each other, that great nations can spend their lifeblood and their treasure on efforts to coerce and subjugate their fellow man,” he later wrote. The next fall, he handed in a 180-page paper on the balance of world power, and announced to his astonished English teacher that his family was moving to Georgia, where he would “form a Republican party and become a congressman.”

“It was the most amazing decision of my life,” Gingrich later told a reporter. “And it gives me certain inner strengths that other politicians don’t have, because I see this as a calling, as something that someone has to do if America is to keep the freedoms we believe in.”

“He always thought big thoughts,” says Chip Kahn, who met him when Gingrich was a grad student at Tulane, in New Orleans. “We would talk for hours about what being a leader was all about, what leadership meant, what politics were all about…He would tell me about talking with Jackie [his wife] about what would happen if she or the kids were kidnapped. He thought he would be in a position of power someday, and might have to make decisions about things like that. He knew he would have to be tough. He and Jackie agreed that if it came down to that, he would have to make decisions for the society, not for his family.”

This grandiose vision was not idle dreaming; it was part and parcel of Gingrich’s personality. He was confident, ambitious, often arrogant. When he arrived at Baker High School, in Columbus, Georgia, he made an instant impression on his classmates by regularly thrusting his hand into the air and announcing, “Question here!” Like a number of his classmates, he also developed a crush on his math teacher. But unlike the other boys his age, Gingrich didn’t leave it at that. She moved to Atlanta; he enrolled at Emory University. One day, Jackie recalls, there was a knock on her door, and there stood Gingrich, seven years her junior. She still remembers the conversation:

“I’m here,” he announced.

“Yeah?”

“Yeah, I came. I’m here.”

“He had made up his mind,” she says with a smile. “We dated and went together for that year his freshman year in school, and we got married the next June.” Newt Was always very “persistent, and persuasive.”

By the time they reached Carrollton, eight years and two daughters later, the grand plan was well under way. In 1964 Gingrich had managed a congressional campaign; in 1968 he had coordinated Nelson Rockefeller’s presidential campaign in the Southeast. In 1971, after a year on the faculty of West Georgia College, he stunned his colleagues by applying, unsuccessfully, for the chair of his department. Later he considered applying for the college presidency.

If he shocked his friends by announcing his congressional candidacy, that was the least of it. “During the first campaign back in ’74, Newt told me he was going to be the kind of congressman that David Broder would come to and like, that he would be the kind of congressman that the media would turn to when they wanted to know what the thinking people in the Republican party wanted to do,” says Lee Howell, his press secretary in 1974. “He said, ‘I’m going to be one of the intelligentsia who sets the course for this party.’ He said that in 1974, when I was still laughing about the fact that he was running for Congress. Sure enough, in the space of a few years, he has achieved all that.”

Gingrich told several intimates in 1974 that his goal was to be Speaker of the House. But Chip Kahn, who ran his first two campaigns and knows him as well as anyone, says his ambitions are loftier than that: “Newt understands the basic principle that one should never say you want to be president. People don’t like somebody at that stage of their life: to be playing that game. But he will be whatever he can be, as high as he can go.”

Though too cocky for some of his faculty colleagues, Gingrich was a popular figure on campus. His classes were exciting, experimental, unorthodox. He organized an environmental studies program and used it to teach the future. He loved the role of instructor, loved being the center of attention. “Newt was always pretty much the way he is now,” remembers a close friend. “If we got together at his house, after a movie, he wanted center stage. He’d turn a social situation into a forum; he really turned my wife off that way. He’s always had a big ego—which made him electable.”

At the time, remembers Lee Howell, then editor of the student newspaper, Gingrich had “moddish” long hair and the tolerant cultural views of a young professor. He would come down to the newspaper office to talk and have a beer (though liquor was not allowed there), or have students over to his house for long philosophical discussions. He didn’t mind if people drank, others remember, or even smoked a little dope. One of his friends lived with a girlfriend, and Gingrich provided emotional support for another couple going though an abortion.

To people on campus, Gingrich was a young liberal. There were so few Republicans in Georgia, and the Democrats were so conservative, that his Republicanism didn’t typecast him. When he ran against Representative John Flynt in 1974 and 1976, Gingrich postured as the young reformer against Flynt, the aging, corrupt conservative. Gingrich’s big issues were ethics—thanks to Watergate and Flynt’s problems—and the environment. In 1976 he sought endorsements from both the liberal National Committee for an Effective Congress and the conservative Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress. He didn’t talk much about the ERA or abortion.

“In 1974 I wrote this speech for his opening night kick-off,” remembers Howell. “I come from a Southern Protestant background, and Southern Protestants quote the Bible. Newt had me take out all the references to God, because he was not very religious—and isn’t very religious. He went to church in order to get a nap on Sunday morning. He became a deacon because of who he was, not what he believed. He did not like us to use God in his speeches; he didn’t want people to think he was using God, because he said that would be hypocritical. He said, ‘I’m not a very strong believer.”‘ In his speeches today, Howell adds, “he uses God quite regularly.”

Gingrich did, however, talk a great deal about ethics, traditional values, and the family. “America needs a return to moral values,” his literature announced, showing photos of the young candidate and his family and describing his church activities as a deacon and as a Sunday school teacher. His wife, Jackie, campaigned hard for him, covering hundreds of miles, visiting country stores, handing out leaflets at high school football games. “Everyone saw Jackie and Newt as a unit,” says Mary Kahn, who covered Gingrich as a reporter before marrying Chip. “He was always talking about the family being a team, about family values. It was a constant, and a big part of his campaign.”

Meanwhile, Gingrich’s own behavior was painting a different picture. During or soon after the 1974 campaign, several of his closest advisors realized he was having an affair. After the campaign, Gingrich seriously considered divorce. He and Jackie went to see a marriage counselor, however, and finally decided to work it out.

This was not an isolated incident, according to others who were close to Gingrich at the time. One former aide describes approaching a car with Gingrich’s daughters in hand, only to find the candidate with a woman, her head buried in his lap. The aide quickly turned and led the girls away. Another former friend maintains that Gingrich repeatedly made sexual advances to her when her husband was out of town. On one occasion, he visited under the guise of comforting her after the death of a relative, and instead tried to seduce her. In certain circles in the mid-1970s, Gingrich was developing a reputation as a ladies’ man.

He was also developing a reputation as an effective but hard-luck candidate: In 1974 he ran into Watergate, which decimated the Republicans; in 1976 Georgia’s own Jimmy Carter topped the Democratic ticket. Both times Gingrich came within 2 percent of victory. Then in 1978 John Flynt retired. This was Gingrich’s year. With the ultraconservative Flynt gone and both the tax revolt and the fundamentalist New Right dominating the national scene, Gingrich swung right. “By ’78,” says Chip Kahn, “Newt was rock-hard conservative. He emphasized different things—he talked about welfare cheaters, he painted Virginia Shapard [his Democratic opponent] like she was a liberal extremist. On some of the social issues, he moved when he realized how central they were to the Republicans. It took him a while to figure that out. Newt understands waves, and he rides waves.”

Gingrich also understands “negative” campaigning. In 1978 he hired Deno Seder, renowned for his hardhitting television spots. “We went and found three inconsequential bills that Shapard had voted against in the Georgia Senate-bills that were so badly drawn that nobody in their right mind would have voted for them,” remembers L. H. (Kip) Carter, Gingrich’s campaign treasurer from December 1974 through 1978. “One was to cut taxes. It was a horrible bill, and she voted against it. So I conceived this ad—it was a spotlight shining on a white piece of paper. A male arm comes out in a pinstriped suit, obviously somebody that you can believe and trust, and lays down this Senate bill. And a voice-over says, ‘Virginia Shapard had a chance to cut your taxes. She knows how she voted; she only hopes you don’t.’ And then we got this fat arm-Virginia Shapard was a little on the hefty side with an iron bracelet that looked like it belonged to Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS, and this big fat hand came out and stamped a big ‘No’ in the middle of the bill. We slaughtered her with that ad. And it was really unfair.”

Another ad showed a similarly hefty arm pulling dollar bills out of a pile. The voice-over charged Shapard with giving money away to welfare people. Campaign literature referred to her as the wife of a wealthy textile magnate, a woman who had gone to “private schools.” It failed to mention, however, that the private school she attended was a college, which made her no different than Gingrich himself.

To top it off, Gingrich seized upon the fact that Shapard, whose husband ran a business in the district, planned not to uproot her family if elected, but to commute to Washington (as Geraldine Ferraro has for six years). “I drew up an ad—I feel embarrassed about this—where I showed a picture of her family and Newt’s family, and I said, ‘This time you have a choice,'” remembers Carter. In a list of contrasts, under the Shapard photo the ad said: “If elected, Virginia will move to Washington, but her children and husband will remain in Griffin.” Under the Gingrich photo: “When elected, Newt will keep his family together.”

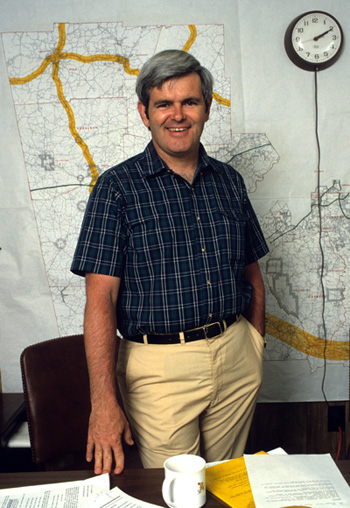

Newt in the 1980s as a US congressman in Newnan, Georgia. Robin Nelson/Zuma

Newt in the 1980s as a US congressman in Newnan, Georgia. Robin Nelson/Zuma

Despite the solid family-man advertising pitch, however, some of Gingrich’s associates could sense what was coming On election night, several of them took bets on how long his marriage would last. Unknown to them, the Shapard campaign staff was doing precisely the same thing. It seemed plain to many that while Gingrich had used his wife to get elected, he would now consider her a liability. “Jackie was kind of frumpy,” explains Lee Howell, who asked Gingrich to be his best man in 1979 but pulls no punches about his friend’s divorce. “She’s lost a lot of weight now, but she was kind of frumpy in Washington, and she was seven years older than he was. And I guess Newt thought, well, it doesn’t look good for an articulate, young, aggressive, attractive congressman to have a frumpy old wife.”

The winning bet, as it turned out, was 18 months. In April of 1980, the candidate who had promised to “keep his family together” told his wife he was filing for divorce. According to sources in whom Gingrich confided at the time, he was already having an affair with the woman he later married.

When I asked Gingrich about this, he did not deny it. “I’m not going to get into those details or the questions about 1974. I think there is a level of personal life that is personal…I had married my high-school math teacher two days after I was 19. In some ways it was a wonderful relationship, particularly in the early years…But we had gone through a series of problems—which I regard, I think legitimately, as private—but which were real. There was an 11-year history prior to my finally breaking down, and short of someone writing a psychological biography of me, I don’t think it’s relevant.”

Private behavior becomes relevant, I suggested, when it contradicts the rhetoric on which a public official has been elected. “Looking back, do you feel your private life and what you’d been saying in public were consistent?”

“No,” Gingrich answered. “In fact I think they were sufficiently inconsistent that at one point in 1979 and 1980, I began to quit saying them in public. One of the reasons I ended up getting a divorce was that if I was disintegrating enough as a person that I could not say those things, then I needed to get my life straight, not quit saying them. And I think that literally was the crisis I came to. I guess I look back on it a little bit like somebody who’s in Alcoholics Anonymous—it was a very, very bad period of my life, and it had been getting steadily worse…I ultimately wound up at a point where probably suicide or going insane or divorce were the last three options.”

The divorce turned much of Carrollton against Gingrich. Jackie was well loved by the townspeople, who knew how hard she had worked to get him elected-as she had worked before to put him through college and raise his children. To make matters worse, Jackie had undergone surgery for cancer of the uterus during the 1978 campaign, a fact Gingrich was not loath to use in conversations or speeches that year. After the separation in 1980, she had to be operated on again, to remove another tumor While she was still in the hospital, according to Howell, “Newt came up there with his yellow legal pad, and he had a list of things on how the divorce was going to be handled. He wanted her to sign it. She was still recovering from surgery, still sort of out of it, and he comes in with a yellow sheet of paper, handwritten, and wants her to sign it.

“Newt can handle political problems,” Howell says, “but when it comes to personal problems, he’s a disaster. He handled the divorce like he did any other political decision: You’ve got to be tough in this business, you’ve got to be hard. Once you make the decision you’ve got to act on it. Cut your losses and move on.”

People in Carrollton were particularly incensed by the fact that Jackie was left in difficult financial straits during the separation, after her surgery. According to Lee Howell, friends in her congregation had to raise money to help her and the children make ends meet, and Jackie finally had to go to court for adequate support, before the divorce decree. In his financial statement, Gingrich reported providing only $400 a month, plus $40 in allowances for his daughters. He claimed not to be able to afford any more. But in citing his own expenses, Gingrich listed $400 just for “Food/dry cleaning, etc.”—for one person. The judge quickly ordered him to provide considerably more. When an article on the hearing appeared in the local paper, many in town were incensed. On election day, a few weeks later, Gingrich’s winning margin in Carroll County fell from 66 percent in 1978 to 51 percent.

In part because of the divorce, in part because of the way he dealt with others, Gingrich has left behind him a string of disillusioned friends and associates, many of whom are now willing to air their feelings. Listen, for instance, to Lee Howell, who is still friendly with Gingrich: “Newt Gingrich has a tendency to chew people up and spit them out. He uses you for all it’s worth, and when he doesn’t need you anymore he throws you away. Very candidly, I don’t think that Newt Gingrich has many principles, except for what’s best for him, guiding him.”

Or Chip Kahn, who ran two of his campaigns and has-known him for 16 years: “I don’t know whether the ambitious bastard came before the visionary, or whether because he’s a visionary, he realizes you have to be tough to get where you need to be.”

Or Mary Kahn: “Newt uses people and then discards them as useless. He’s like a leech. He really is a man with no conscience. He just doesn’t seem to care who he hurts or why.”

L.H. Carter was among Gingrich’s closest friends and advisors until a falling out in 1979. “You can’t imagine how quickly power went to his head,” Carter says. The first time Gingrich flew back to the district, Carter remembers, he “pitched a fit” because Carter was still walking up to the gate to greet him when he arrived, rather than standing and waiting for him. Soon after, they were discussing a supporter who had complained to Gingrich about one of his votes. “I was sort of chiding him about not staying in touch with ‘the people’,” Carter says. “He turned in my car and he looked at me and he said, ‘Fuck you guys. I don’t need any of you anymore I’ve got the money from the political action committees, I’ve got the power of the office, and I’ve got the Atlanta news media right here in the palm of my hand. I don’t need any of you anymore.'”

“The important thing you have to understand about Newt Gingrich is that he is amoral,” says Carter. “There isn’t any right or wrong, there isn’t any conservative or liberal. There’s only what will work best for Newt Gingrich.

“He’s probably one of the most dangerous people for the future of this country that you can possibly imagine. He’s Richard Nixon, glib. It doesn’t matter how much good I do the rest of my life, I can’t ever outweigh the evil that I’ve caused by helping him be elected to Congress.”

Gingrich knew that I had talked to people like Carter and the Kahns. As a parting thought during our second interview, he told me, “I have worked very, very hard to be in a position to help the country save itself and this is a very, very tough business. And I would say that along the way I’ve made a lot of friends and a lot of enemies. Hopefully up to now it’s been marginally more friends.”

In July of 1983, Gingrich made a name for himself in the House by demanding that Representatives Daniel Crane and Gerry Studds be expelled for having affairs with House pages. “A free country must have honest leaders if it is to remain free,” he proclaimed.

“We are in deep trouble as a society… People are looking for a guidepost as to how they should live, how their institutions should behave, and who they should follow.”

“Our decisions are not made today about two individuals; our decisions are made today about the integrity of freedom, about belief in our leaders, about the future of this country, about what we should become.”

For many in Carrollton, the hypocrisy of these statements was too much. “I understood totally that in my hometown and among people who knew me, there would be a lot of people who would be very cynical and would say, ‘Who does he think he is?”‘ Gingrich admits today. “And part of my conclusion is the same one I’m sure you run into. If the only people allowed to write news stories were those who had never told a lie, we wouldn’t have many stories. If the only people allowed to serve on juries were saints, we wouldn’t have any juries. And I thought there was a clear distinction between my private fife, and the deliberate use of a position of authority to seduce and abuse somebody in your care. And I would draw that distinction.

“I would say to you unequivocally—it will probably sound pious and sanctimonious saying it—I am a sinner. I am a normal person. I am like everyone else I ever met. One of the reasons I go to God is that I ain’t very good—I’m not perfect. “

Gingrich cleverly sidesteps the real issue, which is not his private life, but the fact that he misled his constituents, publicly campaigning as a crusader for traditional morality while making a sham of that morality in his own life. If he preaches one thing and does another when it comes to moral issues, his constituents have a right to ask how far his views can be trusted on other subjects. How sound are Newt Gingrich’s ideas about the nation’s future? Is there more than a touch of fraudulence here as well?

Let us examine the key issues Gingrich has pushed this year, beginning with his insistence that the budget could be balanced without tax increases.

In his new book, Window, of Opportunity, Gingrich proposes at least a dozen new or expanded federal programs, plus several new tax breaks. When I suggested to him that the price tag would be $75 billion to $100 billion a year he did not flinch. Yet the book avoids specific proposals for cutting the budget. There is a chapter titled “Why Balancing the Budget Is Vital,” but as Gingrich’s former aide Frank Gregorsky puts it, “There’s a declaration of war, but there’s no ammo in the gun.”

Gingrich and I spent the first half hour of our interview discussing this question. He laid out what he claimed would total $40 billion to $50 billion a year in budget cuts, which might balance some of his spending programs and tax cuts. He then briefly described a program calling for a simpler, less progressive tax system; elimination of waste in government; new “delivery systems” for government services, taking advantage of new technologies; and monetary and interest reforms. He made clear that on some of this—such as monetary and interest rate reform—his understanding was quite casual. Yet several days later he unveiled the package at a press conference and announced that it would “almost certainly” balance the budget by 1989.

Gingrich cheerfully admits that his entire economic agenda rests on the assumption that the US economy can average 5 to 6 percent annual growth—including recession years—for close to a decade, filling federal coffers without a tax increase. Look at “Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, West Germany for 20 years, the United States in the 19th century-there are times and places where you have that,” he told me. In an article on the subject, he pointed to the 5.5 percent annual growth in the US between 1962 and 1967—neglecting to mention that the period fell between recessions, which would bring the average down, and that this spurt of growth, fueled in part by federal spending on the Vietnam War, was so rapid that it touched off the inflation we experienced in the 1970s. In the same article, he claimed we could simultaneously keep inflation down to 2 percent a year.

From 1970 through 1983, our average annual GNP growth—after inflation—was only 2.5 percent. Why would we suddenly come out of such a period into record growth? Gingrich’s answer is instructive: “The whole point of Toffler’s Third Wave and Naisbitt’s Megatrends and Peters and Waterman’s In Search of Excellence and Drucker’s Age of Discontinuity is we don’t know crap about the near future. We are on the edge of an explosion in space and biology, and in electronics we’re going through a revolution in computers. If we are creative, we are potentially where Britain was at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. We’re on the edge of a take-off into what Toffler called the Third Wave.”

In other words, we should bet the farm on Gingrich’s optimistic interpretation of futurists such as Toffler—who made it clear after endorsing Gingrich’s book that he does not agree with all of his politics. But even if Gingrich is right about technology—a dubious proposition in itself—that says nothing about economics. An explosion of technology in agriculture, during the teens and twenties, threw many people out of work and weakened consumer demand, helping to trigger the Depression. Some economists fear a similar impact from computer technologies, which make so much labor obsolete. In addition, Gingrich’s rosy view ignores the short-term impact of the deficit, which has already pushed real interest rates to historic highs. If those rates go much higher next year, as economists predict, we may have another recession. At that point, the deficit could hit $250 billion a year with interest on the debt snowballing so fast that the gap might never be closed. Gingrich prefers to take our chances, however, betting on a decade of growth the likes of which we have not seen in this century.

Next, consider the issue of prayer in the schools. When speaking for this cause, Gingrich always describes the goal as “voluntary prayer”—ignoring the fact that students are already free to pray on their own, voluntarily. He maintains that current Supreme Court interpretation of the law does not even allow students to pray before eating their lunches, or to read their Bibles at school—both of which are simply false.

“The need for a moral revival is a major factor in my commitment to voluntary prayer in school,” Gingrich writes. “For a generation, the American people have allowed a liberal elite to impose radical values and flaunt deviant beliefs.” In a US News & World Report interview, he went so far as to claim that “our liberal national elite doesn’t believe in religion.” Making preposterous statements such as this allows Gingrich to set up a devil—the “liberal welfare state,” run by the “liberal national elite”—and blame it for the decline of moral values in America.

Gingrich knows better, however. In our interview, I asserted that the roots of moral decline lay not in our government, but in our consumer society; which is constantly bombarding us with a glorification of instant gratification, hedonism, sensuality, and the self. In discussing Gingrich with people who know him well, I heard over and over how adept he is at telling people what they want to hear. And sure enough, Gingrich agreed with me, simply redefining “liberal welfare state” to mean the entire society.

If our consumer society is to blame, I next pointed out, the problem lies within private enterprise. “Oh yeah,” he again agreed.. “But see, I’m not a libertarian. I say it pretty clearly in the book, I am not for untrammeled free enterprise. I am not for greed as the ultimate cultural value.” In the book, however, there is no emphasis on regulating private enterprise or forcing corporations to change the advertising messages they constantly beam into our living rooms. How would he deal with the problem? By “preaching a collection of values which over time people come to believe are true. It is closer to a religious, educational… it’s moral leadership.”

And so we come full circle. A congressman who seems to keep two different sets of books when it comes to matters of morality would lead us in a moral crusade. Such are the ironies of American politics.