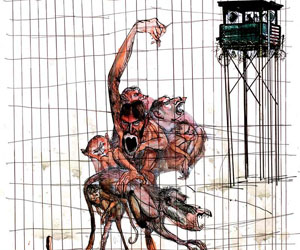

Illustration: Serge Bloch

“I just want you to know that I’m not here representing blm,” archaeologist Blaine Miller reminds me as we drive along the coarsely graded road through central Utah’s Nine Mile Canyon. Nestled into the rugged, sparsely populated Tavaputs Plateau, the canyon is a virtual museum of prehistoric art, with an estimated 10,000 images pecked and painted on its towering sandstone walls. I’ve come to view the dazzling millennium-old renderings of hunters, shamans, and animals before, as Miller fears, they vanish under a coating of dust and grime, thanks to decisions made by his superiors at the Bureau of Land Management, the Interior Department division that oversees some 262 million acres of federal land.

Miller has been with the bureau 33 years, but he hasn’t worked on Nine Mile issues since 2004, the year he publicly griped that his bosses wouldn’t let him adequately investigate a proposed gas-drilling project. Four years and some 200 wells later, this once-serene canyon has become an industrial corridor, and Miller, who wears large aviator glasses and speaks in a lazy cadence, is up in arms over a new blm-approved plan that would bring 600 more gas wells and up to 1,000 truck trips a day through Nine Mile. Although he’s an expert on the canyon’s history and the sole archaeologist in the bureau’s local field office, Miller wasn’t able to view his office’s environmental impact statement for the drilling expansion prior to its public release in February, something Kevin Jones, Utah’s state archaeologist, calls “incredible.”

But Miller has agreed to meet with me as a “private citizen,” and so we spend the day scrambling up to cliff ledges and examining art panels 100 feet above the valley floor—several as clear as the day they were etched, others barely recognizable. “I know this one is fading from all the dust, because I’ve seen it hundreds of times since 1982,” Miller says, pointing to a faint image of figures with splayed hands, triangular bodies, and hunting bows. While his superiors discount his observations as “anecdotal,” a recent blm-commissioned study concluded that dust raised by the trucks is indeed damaging the rock art. The Environmental Protection Agency also has raised concerns about the “physical integrity” of the art due to dust and unchecked ozone pollution in the canyon.

But what incenses Miller most is his office’s new Tavaputs Plateau resource management plan, the master blueprint that dictates how the bureau will oversee the area for the next 15 to 20 years. Normally, these “rmps” take years to complete as myriad competing interests weigh in, but Interior has stamped as “time sensitive” nearly a dozen such plans in six resource-rich Western states—Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, Montana, Utah, and Alaska—and is rushing to finalize them before Bush leaves office.

Foes of the fast-tracking say it’s a ploy to open federal lands to energy firms in a way the next president won’t be able to undo. “There are so many deficiencies—the cultural resources get such short shrift—that the only viable alternative is to go back and start over,” says archaeologist Jerry Spangler, who heads an antiquities preservation group in Utah.

Federal law stipulates that the blm thoughtfully balance land uses including recreation, grazing, environmental protection, and historic preservation. But the new, hastily completed plans stray far from this mandate. In Vernal, Utah, for example, the bureau knew it could save large swaths of prime habitat in the ecologically rich Uintah Basin by scaling back a proposed gas-drilling project from 6,342 wells to 6,117. “They had the science, all the info, to show that a 3 to 4 percent reduction would provide the most benefit to wildlife,” says Wilderness Society lawyer Nada Culver. But the bureau went with the marginally bigger development.

Utah’s six new rmps, covering more than 11 million acres, designate 16,000 miles of new roads for all-terrain vehicles, a change that could unleash atvs on seldom-traveled areas containing sensitive riparian corridors and archaeological sites. And, notes David Alberswerth, an adviser to the Wilderness Society, “Some of these plans make over 95 percent of the lands available for oil and gas development.” The bureau is already on an energy binge: This spring in Wyoming, where studies blame expanded gas drilling for plummeting wildlife populations, it sold new drilling leases covering some 630,000 acres, a move conservationists say will destroy some of the state’s last and richest sagebrush habitat. More sales are expected.

blm staffers attribute the problems, in part, to outsourcing. All of Utah’s resource plans were researched by consultants—Tavaputs’ and another plan for Colorado’s Little Snake River region went to Booz Allen Hamilton, a gop-connected firm that also does intelligence work. Traditionally, rmps had been researched in-house, since field staffers are experts on local land issues, but the Bush Interior Department has farmed out dozens in energy-rich Western states. This worries Steve Madsen, a blm wildlife biologist based in Salt Lake City—especially, he points out, since the bureau determined several years ago that “some of the contractors weren’t up to the task of doing a real analysis.”

In Colorado, the blm‘s White River field office even let oil and gas companies pay for creation of an rmp “amendment” that paves the way for about 22,000 new gas wells. “That’s a little weird,” admits Archie Reeve, a wildlife biologist the bureau often hires for energy-related work. “That private interests would pay for it is really unusual. It would beg the question whether there is a conflict of interest.” blm field office manager Kent Walter defends the deal. “If you look at the way the [agreement] is written, you’ll see that we took extra lengths to make sure that industry has no special treatment,” he says.

He’d be hard pressed to make that claim in Utah, where the outsourcing has cost taxpayers millions of dollars in consulting fees, and wildlife groups are preparing to take the bureau to court. “If they go forward as is,” cautions Kristen Brengel, a Wilderness Society lobbyist, “these six plans will be money down the drain.”