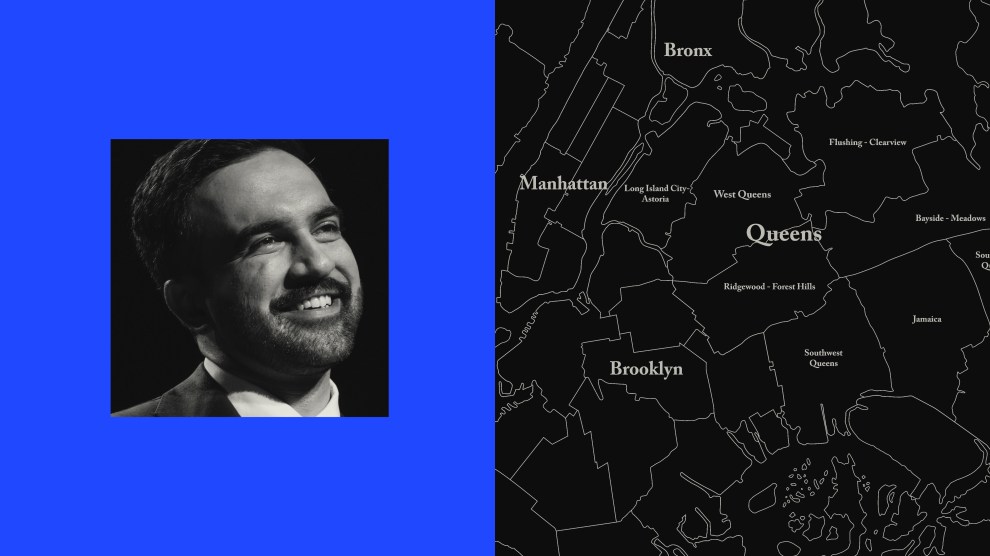

Image: Christoph Lingg/JB Pictures

Well past midnight on a steamy summer night last year, I clutched the handle next to the passenger’s seat in a large U-Haul truck as it bounced through construction barricades on the Cross Bronx Expressway, listening to my cargo crash against the walls as Howard, knuckles white with tension, swung the loose steering wheel to keep us on course. Sheer guts had put him in the driver’s seat. This man, from whom I’ve now been divorced a little longer than the decade we were married, inspired groans from our teenage sons with his contentment in the 55 mph lane on interstate highways. Ryan and Darren, the main glue between us for nearly 20 years, were following in the car behind, all of us exhausted and a little slaphappy after lifting and toting since dawn.

I was acutely aware that this was “the first day of the rest of your life”–certainly, it was destined to be the last day of life as I’d known it. A recently paroled mother/writer/suburbanite, I was about to begin a solo life in New York City, the first time in 47 years I would not have to filter every decision through the needs and expectations of other people. The irony of having my once-husband and two former dependents launch me into independence made this surreal journey somehow more provocative.

The close relationships in our postnuclear family continually baffled friends, but I wasn’t surprised when Howard called from Ann Arbor and volunteered his two-week vacation to help me pack my emptying nest in Connecticut. The sturdy friendship we retrieved from our divorce was rebuilt slowly from the powerful alloy of regret and apology, an interactive chemistry that eventually produces genuine change. We’d never imagined, when we naively recited those vows to love and honor each other for life back in 1970, we would mainly be providing each other unlimited opportunities for mercy.

Mercy is the antidote for the crushing pain that invariably follows the loss of innocence, and only the numb don’t need it. Most recently, Howard had to forgive the hard time I gave him with a memoir I’d just finished on 20 years of motherhood. Long familiar by now with the public compromises of an ex-wife who writes, he said reading the manuscript made him feel “like a jerk or a fool.” When I asked him to identify the offending passages, it took three weeks before he called back. “It wasn’t what you wrote that made me feel like a fool,” he said quietly, utterly undefended. “It’s my life I wish I could revise.” Only in hindsight was it clear how he’d taken this fork instead of that, how decisions made in Michigan affected people he loved in Connecticut. Growing instead of shrinking from the truth, he understood we had no control, of course, over what other people would do with it.

The first review had arrived by fax that morning, shortly before I unplugged and packed the machine. I asked if the noxious label that would be appearing next to his name again and again had hurt. “Yeah,” he admitted, “it got to me.” He smiled ruefully, said he’d had a sudden image of us appearing together on a “Geraldo” show: “Deadbeat Dads and the Women Who Love Them.” We laughed. Then we kept moving.

These are perilous times for anyone living outside “the traditional family,” since the reigning politicians are determined to bring back the social dictatorship of the ’50s. Certainly, the contemptuous labels we’ve had to live under- broken home, latchkey children, absentee mother, deadbeat dad- make it difficult for outsiders to recognize all the thinking and striving most postnuclear families do.

It’s more than a little frightening to see how swiftly the White Guys’ Movement has revived the old formula for ridding a country of its conscience during hard economic times: First, you label whole segments of the population as the Other. Then, when the suffering comes, it’s possible to believe they deserve it. If any of your own relatives turn out to be among the despised populations- a gay son, maybe, a divorced sister- well, mercy is notably absent from the current roster of family values.

Since the neighborhood I was moving into was teeming with Others– accented immigrants, hyphenated Americans, single moms, low- income families–I knew that casualties from the “Contract on America” would be falling within my direct line of vision. It was already impossible to walk through the Upper West Side without encountering lifeless bodies laid out on every block, the parched bottom layer of the trickle-down economy. This reality apparently doesn’t look so bad if you take it in through numbers and indexes in The Wall Street Journal, where investors declare a “good economy” if profits are up. There is scant coverage on the business pages, and rarely any photos, of people going down. Mothers and children are so invisible in the national news, investors might not even know we are out here, laboring in the same economy. Business columnists uniformly regard the collapse of communism as “the triumph of capitalism.” Triumph? From the passenger window, capitalism without compassion looks a lot like Calcutta.

As Howard took the exit on the Upper West Side and aimed the truck down Broadway, I looked out the window at the street people I’d driven past hundreds of times, but never as a neighbor. What did being a “good neighbor” mean in this community, where the utterly destitute and the fantastically wealthy live within blocks of each other? How would I stay in touch with reality, when the daily reality is so unreal? Do I put on an armband, own my affinity with the Others–or do I wear mental blinders, try not to know what I know? I’ve never been able to establish any distance from street people–I keep thinking they’re my relatives. I still scan their faces for signs of my brother Frank, even though I know it’s irrational since I delivered the eulogy at his funeral more than a decade ago.

I’m more or less resigned to my role as an easy mark for panhandlers–a readily identifiable “Sucker Man,” as my son Darren would say in sticky situations, remembering a childhood toy with suction cups that glowed in the dark. I feel especially sucked in by street people with obvious symptoms of mental illness. Frank’s madness used to terrify me, as it did him, and I spent years looking into his wild eyes on psychiatric wards, trying to make contact, trying to stare fear down by knowing it. If you make eye contact with panhandlers, know their stories, the buck in your pocket is already in their hands. I think of these tiny contributions as payments against my huge debt to all the strangers who were kind to Frank.

We lost him periodically, between hospitals and jail cells and mental institutions and home–those scary times when this frail, brilliant, desperately ill young man was “out there” somewhere, totally dependent on the compassion of others. Walking through Manhattan, I still make sidewalk diagnoses of manic depression, autism, schizophrenia, paranoia. . . all being treated on the streets since political reformers in the late ’60s stopped “warehousing” the mentally ill. Few voters back then understood the loathsome “warehouses” were the last stop for the most helpless, or that the alternative to inept and underfunded hospitals would be no care at all. A theater of the absurd, America’s sidewalks reflect the insanity of a national health care policy that now jails the mentally ill before treating them.

Howard had acquired a new nickname that week after he’d dropped a 27-inch television a customer had brought in for repairs. “Hey, Crash!” the wise guys he worked with now greeted him, “How’s it goin’?” With all my material possessions in the U-Haul, I had nothing to lose with Crash at the wheel since my alternate driver was Anthony, the Connecticut neighbor who’d shorn the roof off a delivery van when he plowed into a sign that read, “Clearance-8′.” (“Sure I saw it,” he later told the hospital staff. “I forgot I was in the stupid truck.”) I already missed Anthony and the rest of the gang who regularly camped out around our kitchen table.

I loved that raucous household, blooming with growth and optimism. The quiet solitude after Ryan and Darren left for college felt abrupt. In truth, our quality time together was sometimes down to five minutes a day by then, and the main noise was running water. My landlady had been shocked by our water bills and asked if she should send a plumber to check for leaks. “No,” I confessed, “I’m growing male adolescents here. They need a lot of showers.” I offered to pay the difference, since watering teenagers was more economical and effective than therapy, and ultimately easier on the environment. The boys would emerge in elevated moods, skin flushed and wrapped in terry cloth. Every time I would come across those alarming headlines about young male violence and try to imagine what might save us, I’d think: Showers. If every kid in America had enough private time in the bathroom to get a grip, to feel just great for a moment, wouldn’t it have to improve civilization?

I was lucky to find a “prewar” apartment, Manhattan shorthand for big rooms that haven’t been subdivided into six studios with pantry kitchens and broom-closet bathrooms. Space is so precious in New York, custody suits over rent-controlled apartments are common when couples split up. After postwar prosperity devolved into today’s social Darwinism, whole working-class families now read, watch television, eat, make love, fight, cry, laugh, yell, and sleep all in the same room.

Driving through Harlem a few years ago, I got lost in an urban canyon between tall, crumbling buildings. The narrow street was solidly double-parked, and I noticed every car was occupied: One man was reading by flashlight, another was having a cigarette, a pair of teenagers was car-dancing to a radio, another pair was sinking slowly into the seat. Here, on the streets, people were in the only private room at home. It’s no wonder tempers flare and violence erupts during steamy summers in the city. Who can take a shower in a car?

My neighborhood is “in transition,” as we say, between an elegant past and present cruelties, a microcosm of the growing class divisions in America. One block west of my building, uniformed doormen with epaulets safeguard well-to-do residents who are likely to be liberal, generous contributors to the soup kitchen in the nearby cathedral. One block east, crack vials litter the sidewalks where street people and drug addicts spend the night. The haves and have-nots live cheek by jowl here with remarkable civility I think, given the givens. The thief who would eventually steal my car radio did not break any windows, and left a screwdriver behind on the seat. When the car was broken into again a week later, nothing was taken. Somebody evidently just needed a room.

My suburban habit of getting close to neighbors is trickier here because they come and go sometimes within the same day. It’s hard to learn all their names without mailboxes. And the names sometimes change. The woman with the wild gray hair and bedroom slippers who growls at pedestrians on the west side of Broadway calls herself “Bad Bertha,” but when she’s sitting quietly on the east side, her hair tucked neatly into a bun and feet prettily aligned in ballet shoes, her name is “Irena.” The exuberantly manic guy who works the street outside the Hungarian Pastry Shop calls himself “the Lord’s Apostle,” and sings a gospel rap that sounds like a kind of Gregorian Dixie. One rhyme made me laugh, and a laugh in Manhattan is worth a buck to me: “I love Christ, Jesus Christ/The only Man who’s been here twice.”

But there was a dramatic shift in my street relationships when Howard, the boys, and I were finishing renovations on the apartment. That whole week, nobody hit on us for money. Instead, panhandlers grinned and nodded when we passed them during errands and lunch breaks, as though we were old comrades. Maybe they only solicit suburban commuters, I thought, and now recognize us as neighbors. Then I realized how we were dressed: paint- splattered T-shirts, sweaty kerchiefs, shoes covered with sawdust and Spackle. Crash’s work outfit was truly special–Howard had grabbed a pair of old sweats from the Goodwill pile in Connecticut and didn’t discover the cord was missing until he put them on in New York. We searched the vacant apartment for a piece of string or elastic, but all we came up with from work supplies was a roll of duct tape. Even the craziest panhandlers weren’t tempted to solicit change from a guy wearing a cummerbund of silver duct tape.

If our degrees of separation could melt with a change of attire perhaps the current experiment with “casual days,” when corporations relax formal dress codes on Fridays, should go even further. Maybe Mondays should be down-in-the-socks day. Princely executives could become paupers once a week and get to know the folks who are so invisible to Wall Street Journal readers. In their starched collars and knotted ties and pressed twill, so many of the Suits who bustle down Broadway dodging strollers and shopping carts look either uncomfortable or angry, as if everybody wants their stuff. Most everybody probably does.

But suppose they relieved themselves of this burden once a week, surrendered their gaberdine armor and leather belts for a Goodwill outfit and roll of duct tape. Would they be less angry if nobody was hitting on them? If they got grins and nods on the streets, if they made eye contact and learned the names of the Others, would they be tempted to open up membership in the tight little group of “we Americans”? It’s almost too poignant to imagine, but could the in-it- together camaraderie on the streets even move the white guys to share their drugs? The comprehensive health coverage for Congress and the military is costing taxpayers a bundle, but that entitlement program never appears on the Republicans’ list of “financial burdens.”

Party strategist William Kristol chastised GOP colleagues for compromising their economic goals after Democrats launched an aggressive campaign with the “politics of compassion” during the last presidential election. Addressing a conference on C-Span, he warned his fellow Republicans not to be sidetracked by worries about poor people next time. If the rich could become richer still, objections to ruthlessness become moot: “The politics of growth trump the politics of compassion,” he declared over and over. Greed trumps mercy every time. It was late at night when I heard this game plan in my hotel room almost two years ago. I couldn’t think of anyone to call, anything to do. Now Kristol is publisher of a new, right-wing magazine financed by Rupert Murdoch, and Kristol’s colleagues have taken Capitol Hill. Should I have called 911?

After unloading and returning the truck, my tired crew crashed on mattresses flush with the floors and didn’t get up until noon. The next day, muscles sore but freshly showered, we were in elevated moods after lunch in a local Chinese-Cuban restaurant. “Chinese- Cuban-Americans,” I said, wondering how I would keep track of the hyphens here. “Imagine fleeing the Gang of Four and landing in Castro country.”

“Yeah,” Howard said, “then risking your life in an open boat and washing up here just in time for the Gingrich Gang.” Ryan and Darren gave each other a worried look, familiar by now with their progenitors’ habit of getting worked up over politics. They hated hearing about suffering they couldn’t do anything about. If we were going to saddle them with family values of mercy and justice in these mean times, they wanted to know how to fend off despair. Though we are not regular church-goers, the religion in our postnuclear family is an interfaith amalgam of Catholic beatitudes and Lutheran heresies and Zen koans–I suggested a visit to St. John the Divine. The largest Episcopal cathedral in North America, its towering spire of magnificent masonry now sits sullenly under rusted iron scaffolding, renovations stalled once more while fundraising efforts are applied to more immediate emergencies. Dean James Morton has the formidable task of convincing wealthy parishioners deeply committed to art and historic preservation that their first obligation, as Episcopalians, is to serve the community–in their case, ceaseless waves of troubled kids, addicted veterans, dying homosexuals, and homeless immigrants. In the turf wars between the Suits and the Others in this West Side Story, the cathedral is the parking lot where miracles happen.

Still beautiful despite its present humility, the stately edifice is buzzing with civilian activity. Before New York adopted a recycling program, parishioners brought their garbage to church, where the homeless turned aluminum cans into cash. Two biologists now work out of the church to restore the urban watershed in Upper Manhattan, and hold community workshops on environmental issues. The doors are open to anyone who wants in–on the Feast of St. Francis, when members bring pets to the procession honoring all God’s creatures, even elephants come to St. John the Divine.

In the park next to the interfaith elementary school at the church, we stopped before an installation by sculptor Frederick Franck. A row of six steel panels are aligned on the lawn perpendicular to the path, each with a silhouette of the same human figure cut from the center, the first one slightly larger than life, the last a miniature version of the shrinking figure itself. The inscription quotes the Great Law of the Haudenosaunee, the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy: “In all our deliberations we must be mindful of the impact of our decisions on the seven generations to follow ours.” Franck titled the sculpture Seven Generations, but there are only six figures. The viewer, standing squarely at the mouth of the tunnel, must become the seventh. We each took turns looking through the five ghostly silhouettes, connecting with the tiny figure at the end. Step aside from your place in the human chain, it disappears.

How did the Iroquois chiefs come to their remarkably long view of personal responsibility? How did they make the connection between their business decisions in Michigan and domestic life in Connecticut? Were they all in difficult relationships? Did they speak the hard truth, argue and apologize, let mercy change them? Seemingly larger than life in their war paint and headdresses, did the chiefs declare a casual day at the Haudenosaunee Council, light the pipe and pass it around? Did they inhale?

The architects of the Republican Party’s future can’t be worried about the next seven generations- William Kristol said it’s not even practical to care about most of this one. “You cannot in practice have a federal guarantee that people won’t starve,” he told Harper’s during a candid forum with five other white guys, explaining how Republicans envision the future. Some people will have to suffer, but “that’s just political reality,” said author David Frum. Obviously unaware of Dean Morton’s work with New York Episcopalians, Frum apparently doesn’t think “the sort of people who make $100,000 contributions to the Republican Party” can get behind poor people. “Republicans are much more afraid of angry symphonygoers than they are of people starving to death,” he said.

The main problem with running a merciless government is that in a democracy, millions of voters have to agree to starvation. This requires a certain “finesse,” said media adviser Frank Luntz. “I’ll explain it in one sentence: I don’t want to deliver bad news from a golf course in Kennebunkport.” Republicans are depending on Rush Limbaugh, the undisputed master of political spin, to keep people dizzy and laughing about starvation plans. Labeling people like me “compassion fascists” for trying to get people like him interested in mercy, Limbaugh is so popular even The New York Times compromised its editors when marketing executives hired him to advertise the newspaper. In the new morality of bottom-liners, it’s OK to have a propagandist represent the “newspaper of record,” if it increases sales. Vice must be spun into virtue before we can get to the Republican future, but everybody’s doing their part.

Several years ago, Ivan Boesky spoke to students at the University of California while on tour to promote a new book. “Greed is healthy,” he inspired them. “You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself.” Boesky’s invocation of avarice didn’t stir any action from Republican crusaders fighting “a cultural warIfor the soul of America,” in which Pat Buchanan sees the enemies as “radical feminists and homosexuals.” Talk about a dazzling public relations coup: The party championing morality in America has declared that charity is impractical, greed is healthy, compassion is fascist, and mercy is the responsibility of other people. If future schoolchildren have to recite a prayer written by these folks, whatever will it say? “Dear God, please give me more of everything than I’ll ever need and I promise not to care about anyone else.”

Though I’m not an Episcopalian, visiting St. John’s always makes me wish I could pray. I envy the solace my family and friends have talking to God. My own spiritual meditations are generally addressed to my brother Frank, the euphoric madman who left abruptly at age 36, delirious with love and forgiveness as he answered God’s call. I still want him to tell me: Is heaven better than the transient hotel where the Chicago police found his body? Sitting in the garden at St. John’s, I remembered our last conversation on the lawn at Elgin State Hospital. He asked me why I loved him and I said, “Because you are a fool, and I love fools.”

“But Jesus said, ‘There are no fools,'” he replied, quoting a scriptural fragment from his seminarian days.

“I know,” I replied. “But I think what Jesus really meant is that we are all fools,” I said, paraphrasing J.D. Salinger. I told him I thought he was the king of fools. He laughed, said I must be the queen. I don’t blame God for the scrambled thinking that led to Frank’s suicide. I can’t even be sure there is a God. I believe my divinely crazy brother heard God say what he wanted to hear. Many mentally ill people think they are in direct touch with the Almighty. The Lord’s apostle outside the pastry shop, the toothless guy at D’Agostino, even Bertha on her bad days will offer the panhandler’s benediction: “God bless you,” they say, whether the quarter comes or not. Republican Christians today are getting some frenzied directives as the political scene becomes ever crazier, and they too hear exactly what they want to hear: God wants everybody to get married, wants women to stay home, doesn’t want gays in the military, doesn’t want national health insurance. I can’t share their faith that a supreme benevolence is behind all these messages, but if the polls are correct and most Americans do think somebody’s God should be directing all our lives, let’s please not pick the one who’s inspiring pro-lifers to get automatic weapons. Until we have a firmer grip on our common reality, maybe we could all follow the harmless god who’s telling the autistic disciple on 34th Street, over and over: “Go to Macy’s nine-to- five, Go to Macy’s nine-to-five.” We could leave the credit cards home, stay out of trouble. Just look.

It was a beautiful summer night on Broadway as we walked home from our last dinner together, grateful there were no more boxes to move. When a U-Haul truck rattled down the street, Crash laughed and asked, “Do you think they’d have less business if the company was named, ‘U-Bust-Your-Ass’?” Our laughing foursome attracted looks from our neighbors, but few grinned or nodded, as if we’d become strangers again. Darren noticed too.

“This is too weird,” he said. “People are staring at us because we look so normal. Like Mom and Pop and the two boys from Iowa.” He was struck by the irony of having been labeled the weirdos in almost every neighborhood we’ve lived in, then arriving here–where weirdos abound–and being mistaken for regular guys.

“We should wear a sign,” he said. “We’re Not What You Think.” Maybe everyone should wear that sign through the next election, since there’s so much confusion about the Other. As bad decisions in Washington crush good people in Harlem, even “liberal” politicians are telling us to prepare for further compromises–live a little leaner, do more charity work, tighten our belts. What can they be thinking? My neighbors are already living in cars, doing-it-yourself, holding pants up with duct tape. There is plenty of self-help and personal responsibility out here, where people watch each other’s kids and take mostly working vacations, if we take them at all.

How did the white guys ever get the impression they are doing all the work? Because they are earning all the big bucks? Why are the Republicans so mad–why so furious with mothers? Do they need more Prozac? Since all the female labor sustaining them at home and at work is so invisible, so seemingly profitless, they can’t seem to hold the picture that somebody’s valuable work is responsible for the fact their children are alive, their Contracts are typed. The arrogance and ignorance of the current political leadership is so stupefying, you don’t even want to argue with these boys–you “just want to slap them,” as a high-ranking official recently told Molly Ivins. Maybe that’s why the white guys loathe mothers so much- we remind them they have to share, take turns, grow up.

The next morning we loaded the roof of Howard’s car so high with the boys’ sports equipment, easels, and trunks, we had to make one last trip to the hardware store for longer bungee cords. It was a hectic departure as the Clampetts hit the road, and I waved from the curb as they mouthed their final goodbyes through the window. Still smiling, I stayed on the curb for a long time, sorry the party was over. Letting go rarely comes naturally to me, and I felt my worry reflexes kick in as the car turned the corner.

Almost every family value Howard and I tried to give our sons will give them nothing but trouble, if they choose to live them. As two young, educated white guys who could qualify as insiders if they got behind the Contract on the rest of us, there are bound to be days they’ll feel like Sucker Man, stuck with mercy when greed is called trump. I know it’s a peculiar wish for a mother, but I hope they never quite fit in with their crowd. Certainly their affinity with their dad, a truly original odd man out, was a heartening sign. I could see them all laughing for the next 750 miles. Folding my arms, I looked up at the cathedral. I wished I could pray. I remembered my religious instructor’s belief that we were all fools, walking from one hallowed ground to the next. Dear God, I thought, please let us be merciful fools.

Mary Kay Blakely, a contributing editor at Ms. and The Los Angeles Times Magazine, is author of American Mom: Motherhood, Politics, and Humble Pie; and is working on a new book about political depression called Red, White, and Oh So Blue.