Indigenous leaders and water protectors at a 2021 "Treaty People's Gathering" in Clearwater County, Minnesota, protesting the construction of Line 3Alex Kormann/AP

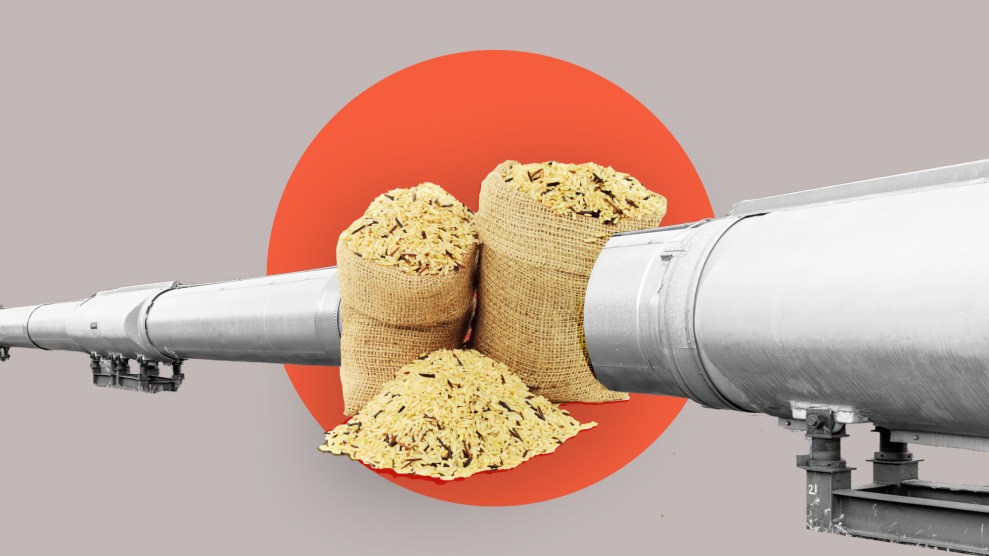

Earlier this year, I wrote about a unique lawsuit aiming to stop the further construction of Line 3, a tar-sands oil pipeline built in 2021 that stretches for 330 miles across northern Minnesota and has been fought fiercely for nearly a decade by an Indigenous-led movement. The suit had an unlikely plaintiff: Manoomin, a grain known in English as wild rice that grows throughout the wetlands of northern Minnesota and holds immeasurable significance for Anishinaabe people. A 2018 White Earth law gave rights to the plant, part of an international rights of nature movement that seeks to flip dominant legal frameworks on their head. According to the complaint filed in August, the construction of the pipeline threatened Manoomin’s “inherent rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and evolve, as well as inherent rights to restoration, recovery, and preservation.”

Through a novel legal maneuver that used the rights of nature, treaty law, and the independent jurisdiction of tribal courts, it seemed possible that Line 3 could be halted, at least for a bit.

But the tactic didn’t pan out. On March 10, the White Earth Band of Ojibwe Court of Appeals dismissed the August lawsuit against Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources filed by tribal leaders on behalf of Manoomin, citing a lack of legal precedent.

The lawsuit targeted a permit by the Department of Natural Resources that allowed pipeline owner, Canadian corporation Enbridge, to pump 5 billion gallons of water from the ground to clear the route for the pipeline construction. Not only was this permit given, “abruptly, unilaterally and without formal notice to tribal leaders (quasi-secretly), and without Chippewa consent,” but it would also negatively affect the level and quality of the surrounding waterways where Manoomin grows, the complaint alleged.

The crux of the case was whether White Earth would be allowed to raise a legal claim in tribal court about something that happened off-reservation. When the Anishinaabe ceded their land to the United States, they retained what are called “usufructurary rights” to hunt, fish, and gather foods including wild rice as part of a series of treaties. The argument put forth by the mastermind of the case, White Earth tribal attorney Frank Bibeau, was that these treaty-protected rights extend into the ceded territories and could be enforced there by the White Earth Tribal Court.

The court disagreed. “Such exercises of sovereignty must take into account the longstanding legal and judicial framework,” wrote Judges George W. Soule, Lenor Scheffler Blaeser, and David Harrington in their conclusion. “A tribal court lacks subject matter jurisdiction to hear claims based on a nonmember’s allegedly unlawful activities that occur off reservation,” and treaty law does not “confer tribal court jurisdiction” off-reservation.

The precedent they relied on is whats called the Montana doctrine, named for a 1981 ruling that allowed tribes to address “what is necessary to protect tribal self-government or to control international relations,” but the court maintained those powers do not extend to nonmembers off-reservation, such as the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

The judges weren’t outright dismissive of the historic lawsuit, though, commending the “efforts to expand jurisdiction by Band legislation and the use of Tribal Court to address matters such as raised in this case,” and encouraging similar efforts “as an exercise of inherent tribal sovereignty.”

In response to the dismissal, White Earth attorneys Bibeau and Joe Plummer filed a brief on April 7 requesting the court to reverse its order.

This lack of legal precedent presents a persistent problem for the rights-of-nature legal movement—a potentially transformative paradigm shift in environmental conservation that in the United States legal context remains almost entirely symbolic in its real world effects. It was thought that in the case of the Manoomin lawsuit, the addition of treaty rights and tribal court could combine to become one of the first successful rights-of-nature effort in the movement’s still-young history. With the release of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report on Climate Change this week that warned of the requirement for “immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors,” the need for legal systems to adapt becomes all the more pressing. It would be even better if combating climate change and recognizing Indigenous sovereignty didn’t require unique legal strategies. And could be found in political will.

This article has been updated to reflect a brief filed to oppose the order from the White Earth Band of Ojibwe Court of Appeals.