Mother Jones illustration; Getty; Unsplash

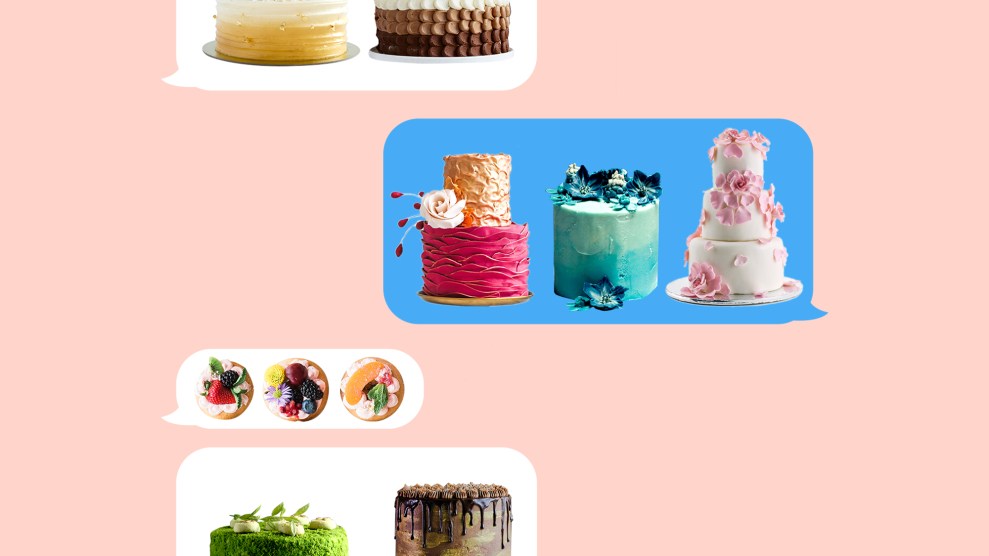

A good night out used to mean draping a silver chain around my neck, tending to the melodrama of a friend spotting their crush at the club, and finishing perched over a taco stand in downtown Los Angeles. Those nights are sadly gone. Now the signs of a pandemic pleasant evening reside in the digital sphere—in group chat and DMs—where my friends and I fire off messages about the elaborate dinner parties we wish we could throw. More often than not, we dwell on what we should have for dessert. In recent months we’ve become increasingly obsessed with a certain genre of heavily adorned, pastel-colored cakes.

The first time I saw this style of cake was when my friend Maddie sent me block.them’s Instagram page. A Chicago-based cake account, the page features cakes overloaded with fig halves, kumquats, ruby pomegranate jewels, yellow and pink dragon fruit, sprigs of rosemary and red roses. In the caption of one particular delight, the baker Ken Folk says the inside contains a vanilla-and-black-pepper base with a “tamarind cream cheese frosting.” I was smitten.

@block.them isn’t the only baker working toward extreme adornment. Since the beginning of the pandemic, dozens of unconventional cake accounts have spawned over Instagram, from @nommel_gobble’s drippy watercolor cakes dressed with flowers and unusual plants to @eatnunchi’s dreamy translucent jelly cakes (which take on transcendent shapes like that of a snail or an ear of corn) to @dreamcaketestkitchen’s carefully fruit polka dotted cake mounds.

But what do we call them? How do we categorize them? One friend of mine, Caitlan, suggested these were of the “soft core” variety. Another friend said they’re “internet cakes.” Earlier in the pandemic, the New York Times wondered if these cakes might be classified in the woodsy goblincore or the pastoral utopia cottagecore aesthetic. In many ways, these desserts follow in a long line of queer food culture, questioning what a cake is and can be. Just look at the gilded grotesque dinner parties put on in the past by New York–based queer food collective @spiral_theory_testkitchen for reference. One of the test kitchen’s co-founders and chefs, poet Precious Okoyomon, told Vogue, “When people taste our food, they’re like, ‘What the fuck is in my mouth?’”

Since we’ve been at home, we’ve graduated beyond growing scallions in our windowsills and dabbling in sourdough starter. The pandemic has ushered in a new kind of play and abstraction in the kitchen, a ripe ground for spontaneity and surprise in a time when the days all start to blend together.

Were she alive today, I think Susan Sontag would say these cakes demonstrate the epitome of camp. In her 1964 essay “Notes on Camp,” the philosopher and critic argued that camp art lies in the intense juxtaposition between “extravagant” and “rich form.” It must, in part, contain a fiction; it is a “vision of the world in terms of style…the love of the exaggerated.” These desserts are “cakes” in quotations marks in the best way.

Now in the absence of physical queer gathering spaces—the club, dinner party, community center, cafe—this genre of sweet delight has become a salient terrain for celebration and exploration for me and my friends. It isn’t just about the cakes themselves, it’s about the weird artistic community they foster, their inherent connection with botany and the natural world, and their insistence on play and imperfection. I dream one day of foraging through my neighborhood with my friends, collecting fresh figs and lavender flowers, dehydrating, emulsifying, brûlée-ing. I look forward to the disaster of baking, of making a messy cake mound and trying hopelessly to catch it in its best light. Those days still feel and are far away. But until then, we have the cake—in all its dreamy forms—as our disco.

An earlier version of this article misstated the location of the baker @block.them. They are based in Chicago.

Image credits: Brooke Lark/Unsplash, Holly Stratton/Unsplash, American Heritage Chocolate/Unsplash, May Lawrence/Unsplash; Getty