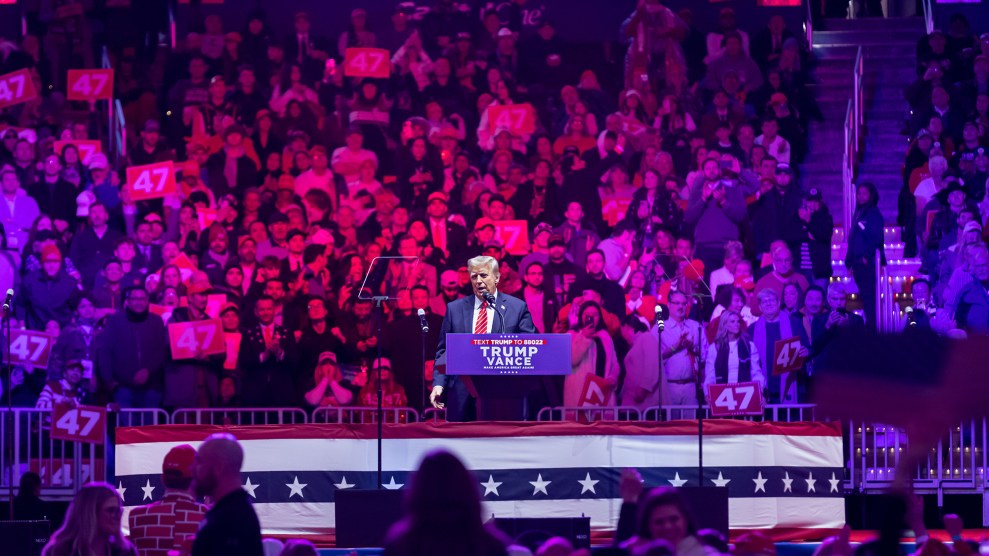

Jazmine Sullivan performs the national anthem prior to Sunday's Super Bowl. Ben Liebenberg/AP

“Gotta stop getting fucked up. What did I have in my cup? I don’t know where I woke up. I keep on pressing my luck.”

Those are the opening lines of Heaux Tales, the newest LP from Jazmine Sullivan. The track is called “Bodies,” and in it the singer addresses herself like someone evaluating a hangover in the mirror. “Bitch, get it together, bitch,” she sings. “You don’t know who you went home with.” She is chiding herself, but there is also a touch of celebration in the way her voice jumps when she sings of “piling on bodies on bodies on bodies.”

Heaux Tales is an honest, prismatic evaluation of what it means to be a hoe. Sullivan’s subject is the promiscuity myth that all women know but Black women know better than anyone. The album is about the sex, but it’s also about the emotions that surround it—regret, lust, shame, satisfaction—and about the women who bear them, then get labeled hoes for their troubles. These are usually Black women, and like the narrator of “Bodies” they are full of contradictory feelings, alternately resisting the designation and celebrating it on their own terms.

Obviously, “Heaux” is not a misspelling. Sullivan is imploring Black women to reanimate the concept of the hoe, not reclaim it. With Heaux Tales, she is stripping the word “hoe” from its usual context and reshaping it to fit the perspective of a Black woman, the woman who feels like there was never any other option than to be a hoe. Stereotyped as Jezebels, mistresses, and—a personal favorite—”pass-arounds,” Black women have long been stamped with a scarlet “h” for “hoe”; the specific slurs may change from generation to generation, but the intent is always the same—to justify the sexual abuse of Black women by suggesting they are willing, even eager participants, and to relegate women who dare to be unabashed in their sexual experiences to the underbelly of society. A “hoe” is something a white patriarchal society says you are; a “heau” is a label you can embrace. The word is Frenchified, refined, divorced from its sullied connotations and infused with a Black woman’s sense of herself.

Heaux Tales is indeed an album by, for, and about Black women, from the R&B notes Sullivan hits to themes such as ascending from poverty. After “Bodies,” Antoinette Henry has the first of six “tales.” These are spoken-word interludes by women in Sullivan’s life that tackle an aspect of hoedom. Each is followed by an R&B interpretation of the same topic. Sullivan, who sang the national anthem before Sunday’s Super Bowl, explores plenty of things anyone can relate to, but there is no taking this album from the mouth and perspective of a Black woman. She discusses gendered double standards and the need for women to claim their own vaginas, a truly radical idea for plenty of women, as Antoinette emphasizes when she says: “And really it’s our fault. We’re out here telling them that the pussy is theirs, when in reality—it’s ours.” Sullivan follows it with the uptempo, groovy, and slightly dancey “Pick Up Your Feelings,” a call for women to guard their emotions, and to dismiss men who play with them, and even be as unconcerned as men in their pursuits.

“Put It Down” and “On It” are the sort of classic, explicitly sexy ballads one can always expect from an R&B album, but they follow Ari Lennox’s riveting tale about being “dickmatized,” which explores the utterly ridiculous—and embarrassingly true—notion that a woman would put up with almost anything for the right type of pleasurable experience. “I was damn near willing to let him just talk to me crazy. Like, yes, daddy, yes, okay,” she says. “Like, I was literally willing to ruin my career. Um, if this ever came out, who it was, you would be like, ‘Bitch, do you know what Google says?'”

Been there, done that. This is a moment for all women who have dealt with a terrible man, which is to say the average woman. She knows that the pickings of worthy men are slim. When it comes to sex, women just do not need or care to be the moral epicenters of the world. “That dick spoke life into me,” she goes on. “Invigoration, blessings, soul, turmoil. But, heaven, Jesus, Allah, sorry. Please, God, understand. This is just my truth.” Ari is making a confession, but not as a penitent. And she leaves a couple questions unasked: Why should she be judged for sleeping with an apparently terrible man? Why not judge the man for being terrible? As Antoinette states earlier, “We are sexual beings, too.”

The album works from themes surrounding sexuality that have been explored by other Black women. Years ago there was Lil Kim, announcing on Hard Core, “I used to be scared of the dick, now I throw lips to the shit,” knocking down the wall that stopped Black women from openly and explicitly expressing their sexuality, and then there was Beyoncé, unashamedly telling the listener what she finds pleasurable (“Rocket,” “Blow”). SZA, in 2017’s “Doves in the Wind,” told men they “do not deserve pussy.” And now here is Sullivan, describing sex in the blunt transactional terms that are always available to men but typically denied to women, particularly Black women.

“Bitch, every time you sleep with—even if you married—you have tricked in your fuckin’ marriage,” Donna declares in another tale. “You fuckin’ your husband, so you can get what the fuck you want!”

Let the church reluctantly say, “Amen.”

A hoe wants something in return; so does the average woman who enters a marriage. The former transaction is demonized; the latter is a sacrament. Heaux Tales isn’t interested in exposing the hypocrisy so much as showing how the social order needs its demons—marriage isn’t marriage without hoes to give it meaning.

Heaux Tales is deeply unsentimental about sex, but that does not mean it is callous, as “Rashida’s Tale” and “Lost One” demonstrate. The two tracks are the emotional crux of the album. Rashida regales the listener with the story of how she hurt someone she loved (notably, another woman) by cheating on her, describing the flood of emotions that came with the betrayal. It hurts to hurt people. It especially hurts to hurt a person you love, and it hurts when you find yourself pleading: “Just hear me out before you let it go. There is one thing I need for you to know. Just don’t have too much fun without me.”

What does it mean to hurt someone else? Why do things that have no good consequences? Why do we self-destruct and self-sabotage? Why do we act without thinking? Sullivan is digging deep into her emotional intelligence as she comes out with uncomfortable answers, as therapy often produces. “I know I’m a selfish bitch, but I want you to know I’ve been working on it,” she sings. The album is a kind of therapy for people who intimately know the love-and-sex hustle and who feel its social burdens in everything they do. It is for the women who alternate between vulnerable introspection and brassy self-assertion on any given day.

“Money makes me cum,” Precious says in her tale, describing her attraction when she sees “a man thriving, out here hustling….I’m not dealing with anyone who does not have money, because I know my worth.” Sullivan keeps pressing on this idea in “The Other Side,” telling the story of the Black woman’s hustle and what a woman might do to have a better life. “I’ma move to Atlanta,” she sings. “Ima find me a rapper. He gon’ buy me a booty.”

She is describing heauxing for what it is: work. Society presents such an avenue as one of the few viable options for a better life yet denigrates those who choose to take it. Sullivan’s album is a declaration of owning that choice and all the feelings that come with it.