When the US targeted Russia’s oligarchs after the invasion of Ukraine, the trail of assets kept leading to our own backyard. Not only had our nation become a haven for shady foreign money, but we were also incubating a familiar class of yacht-owning, industry-dominating, resource-extracting billionaires. In the January + February 2024 issue of our magazine, we investigate the rise of American Oligarchy—and what it means for the rest of us. You can read all the pieces here.

As the pandemic took hold and tensions between the haves and have-nots simmered, I couldn’t log in to social media without spotting an image of a guillotine, the enduring symbol of the French Revolution. By then, a similar ire toward the wealthy had already begun to seep into cinema, as evidenced by the success of the 2019 Korean film Parasite—pitting a striving family against a grotesquely wealthy one—which swept the Oscars just before the pandemic sent us all into lockdown.

Filmmakers have previously scrutinized wealth’s impacts on society: Charlie Chaplin humanized the impoverished, and films like My Man Godfrey (1936) and The Grapes of Wrath (1940) exposed economic inequality. But for much of the 20th century, the rich were often fetishized. Films like The Fortune Cookie (1966), McKenna’s Gold (1969), and The Ruthless Four (1968) portrayed a deep desire for riches, either through tender or gold, and scamming featured heavily in the journey to acquire it.

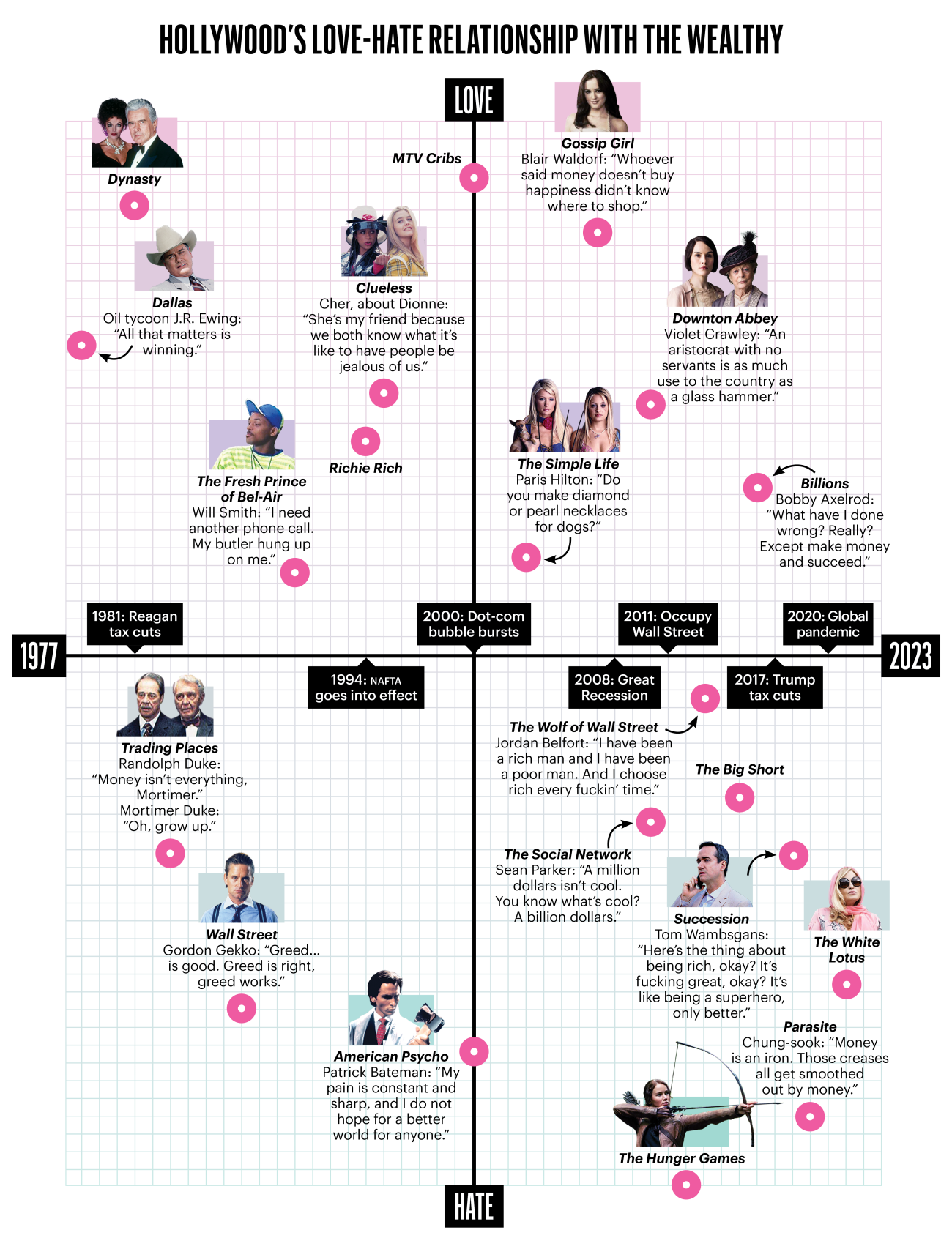

“From World War II to 1980, the country had a lot of shared prosperity,” explains labor reporter Hamilton Nolan. Reagan-era TV series like Dynasty and Dallas centered prosperous plutocrats; later, reality shows like MTV Cribs and The Simple Life provided entry into the opulent lives of real celebrities, sometimes gently mocking them but never exposing wealth’s underbelly. Whenever an economic downturn was depicted onscreen, the blame was usually assigned not to the upper class but rather to some inscrutable force.

But income inequality continued to widen, and the 2008 banking crisis revealed the fallacy of blindly trusting Wall Street. “We fetishize wealth. We celebrate wealth. At the same time we’re making it materially less possible for people to get those things,” Nolan notes.

As with most things in pop culture, trends tend to follow an ever-revolving cycle. The fixation on fraudsters that showed up in so many films in the 1960s returned a half century later. In 2018, Elizabeth Holmes’s former multi-billion dollar company Theranos shuttered. Then 2019 was deemed the year of the scammer. A documentary on the disaster that was Fyre Festival occupied everyone’s Netflix queue, while Anna Sorokin, also known as Anna Delvey, was sentenced to 4 to 12 years in prison.

Films explored the class divide and reflected the heightened desire to establish wealth by any means necessary; think Uncut Gems, The Irishmen, and Hustlers. Geoff Nelson wrote for BuzzFeed of this pivot: “There was a noticeable uptick in the quality and quantity of the class conversations in 2019’s movies, perhaps because debates about the economic future of the US are intensifying.”

No film captured the growing resentment between the rich and the poor better than Parasite. While tensions between the haves and have-nots were brewing in both countries, it took a South Korean filmmaker to make the theme resonate with US mainstream audiences. “It’s been taking Hollywood a really long time to catch up to this idea of class resentment in this country,” Inkoo Kang, television critic at The New Yorker, told me when I asked her about Parasite’s success. “It feels to me very much like the reason why this class-based entertainment is catching on [in the US] probably has a lot to do with projects [in Korea] tackling those themes in a way that they are not here.”

Even as the backlash grew stronger, a fascination with extreme wealth continues unabated, especially on social media, where, as Kang puts it, “whatever version for you is the most attractive version of wealth is available for you to find.” On TikTok’s Hello Fashion, digital editor Natalie Salmon breaks down the differences between Old Money (Think Great Gatsby and Princess Diana), Quiet Luxury (minimalist designers like The Row and Loewe), and Rich Girl (Birkin bags and French Riviera vacations). #Oldmoney and #oldmoneyaesthetic had over 1.3 billion views in 2022. With a lot of these sartorial tips and vacation choices, the veil over how the rich play and dress has been lifted. “There’s always been a fascination with rich people and fancy people and how they live,” NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour host Linda Holmes says; “I don’t think that will ever fade.”

We may always be mesmerized by the wealthy, but we’re increasingly critical of them, too. After Covid hit, “the really intense pandemic time kind of radicalized a lot of working people,” Nolan told me. This past summer, also called “Hot Labor Summer,” the country witnessed a tidal wave of labor strikes not seen in decades. Everyone from SAG-AFTRA to WGA to the UAW galvanized hundreds of thousands of workers to fight for better conditions.

Hollywood fixated on class resentment with renewed vigor. From The Menu to The White Lotus, getting even with the rich was in vogue. These revenge fantasies emerge when workers “have to claim some sort of power and dignity and living wages for themselves,” argues culture critic Soraya Nadia McDonald.

When I asked Kang if she thinks these kinds of revenge fantasy movies will fade away when it’s no longer hard to live in America, she says with a giggle, “So you mean, never?” While I was writing this article, the WGA had just struck what was considered an “exceptional” deal with AMPTP. There is no question Hollywood writers, who had months of fighting and deliberating for better working conditions, will return to their Final Script pages or writers’ room with stories that mirror that struggle and eventual triumph. Given the wave of workers striking all over America in various industries, there will be more than enough audiences eager to receive them.

Photo credits: American Psycho: Lionsgate; Clueless: Paramount Pictures; Dallas: CBS Photo Archive/Getty; Downton Abbey: Nick Briggs/Carnival Films/HBO; Dynasty: ABC; Fresh Prince: NBC; Gossip Girl: The CW; Hunger Games: Murray Close/Lionsgate; Simple Life: Sam Jones/20th Century Fox TV; Succession: Graeme Hunter/HBO; Trading Places: Paramount; Wall Street: 20th Century Fox; White Lotus: Fabio Lovino/HBO