In April, bestselling children’s book author Shannon Hale published book number 10 in her acclaimed Princess in Black series. For those who don’t have an elementary schooler in their lives and therefore may not be as familiar with the series as I am, here’s the gist: Prim Princess Magnolia lives in a charming castle doing dainty princess things with her unicorn Frimplepants until the “monster alarm” sounds. Then Magnolia transforms into a tough warrior and battles bumbling, goat-eating monsters while shouting commands like “Behave, beast!” In her latest addition, Princess in Black and Prince in Pink, Hale introduces us to one of Magnolia’s new friends—a prince who happens to like wearing capes, tunics, and tights the shade of tropical flamingos.

Like the previous books in the series, Prince in Pink was a commercial success and quickly racked up hundreds of positive reviews online. “What a sweet, wonderful addition to the series,” gushed one five-star review. “I love that the canon of superheroes keeps growing, and that they’re all so different from one another.”

But not everyone was so effusive. Twenty-five percent of the book’s Amazon reviewers were so offended by the mere presence of the prince, they gave it the damning one star. “Why does this series need an effeminate boy character?” wrote one unhappy reviewer, summing up the complaints. “This is just another grab to warp a fun series for children into a tool for woke indoctrination.”

In a Twitter thread a few weeks after the book came out, Hale addressed the hypocrisy of readers who embrace a strong female character but reject a male character who isn’t conventionally macho. “A girl who wears black and fights monsters: acceptable,” she wrote. “A boy who wears pink and likes to decorate for a party: wrong.” Dozens of readers replied, many of them expressing gratitude for Hale and her characters. One enthused, “My little tough-as-nails girl and my boy who likes to cuddle and sing, LOVE your stories. Buying this one now—can’t wait to introduce them to this sweet prince in pink!”

Most authors would have ignored the rest of the comments and moved on. But Shannon Hale is not like most authors. A few days later, she returned to her thread and added a tweet. “I feel so much compassion for this reviewer,” she wrote. “Like me, she grew up in this world that demeaned the feminine. That told her that who she is, is fundamentally shameful.”

Much like her princess protagonist, Hale—who has written dozens of other books for kids and teens—moves between two worlds. As an author, she gives passionate talks about the value of including people of all races and genders in children’s literature. On Twitter and in her newsletter, she speaks out against policies that she considers hateful—abortion bans, for instance, and rules that seek to limit gender-affirming medical care. In recent months, she has vociferously opposed the rising tide of book bans, especially in her home state of Utah.

Hale’s other identity is as a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. During times of such polarization, her life as both a liberal activist and a Mormon can appear confounding. In her 2017 book Real Friends, the first in her trilogy of graphic novel memoirs about her childhood and early adolescence, she included imagined conversations with Jesus that she had as a child. One apparently secular reviewer on GoodReads complained, “I honestly think this was just about Jesus. There was no warning for all the religious propaganda and imagery.” Other, presumably more conservative, readers objected to what they saw as inappropriate themes in the book, such as kids kissing. “Progressive people are kind of suspicious of me,” Hale tells me, laying out the dynamic. “And then for books that I’ve written that never even had a single cheek kiss, I’ve gotten hate mail from conservative people.”

Shannon Hale

Getty

Though it seems to irk plenty of parents, this moving between two communities is part of what makes Hale good at creating characters that children love. For “students who have not always had access to books where they can see themselves, their family, their peers,” said Kasey Meehan, who leads the initiative against book bans at the reading advocacy group PEN America, “her message is the opposite: You do exist, your story does matter.”

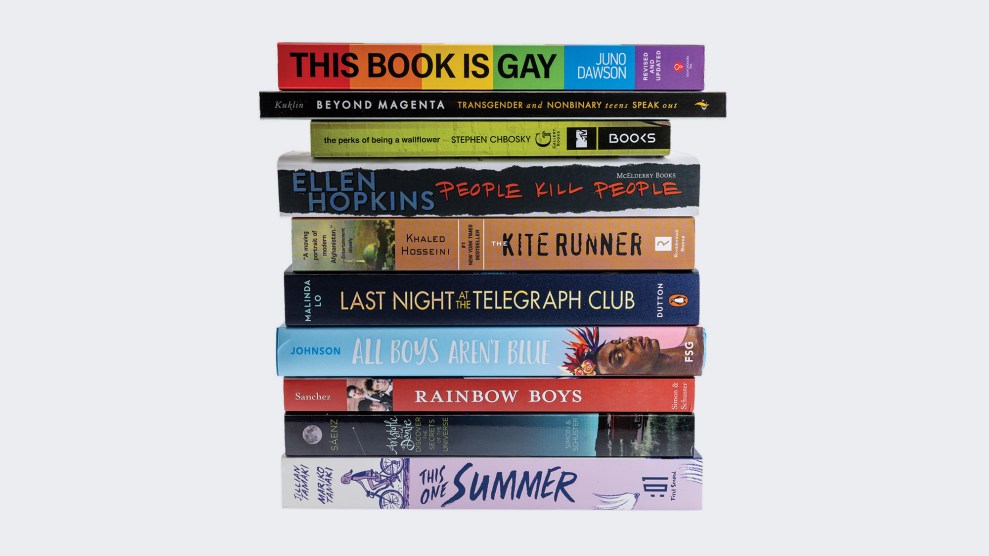

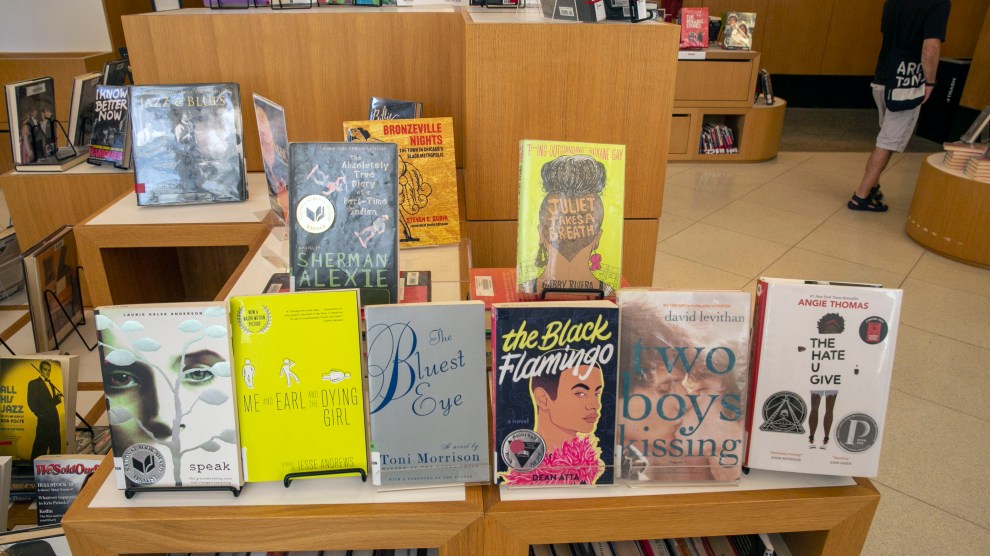

In a report last year, PEN America found that more than 1,600 books had been banned in the 2021-2022 school year alone, most of them because of identity themes—gender, race, and sexuality. While not explicitly dealing with those themes, at their core, all Hale’s work concerns a nearly universal subject intimately related to identity: how it feels to be a child who doesn’t fit in.

But not everyone wants to admit that children often feel different and left out. Behind every book ban, Hale told me, are parents and school administrators scared of the rapidly changing world—a contemporary echo of her own conservative Mormon upbringing. In the grand tradition of Judy Blume or Beverly Cleary, Hale is very much a spokeswoman for her times. She seems to appreciate the fact that she can act as a kind of bridge between worlds—or maybe as an ambassador. As any reader of Princess in Black knows, the so-called monsters aren’t always what they seem.

On a chilly morning in April, I drove 40 minutes south from Salt Lake City to Saratoga Springs, Utah, to watch Hale give an assembly at Thunder Ridge Elementary School. The sun illuminated the snow-capped Wasatch mountains, and I could see why the Mormon pioneers chose Utah as their Zion. As I approached Saratoga Springs, both sides of the highway were flanked by developments carved into the gently rolling foothills. The houses were unfancy yet enormous—giant earth-toned boxes with play structures in the back, designed to accommodate large families. One of them had a tube slide snaking down from the front porch into the backyard.

At Thunder Ridge, about 200 kindergartners through third graders filed into the cavernous gymnasium, their teachers gamely directing traffic. Hale’s twin nephews, third graders at the school, shyly shuffled up to the front to introduce her, informing their classmates that they knew the famous Shannon Hale not only because of her books but also because she was their aunt.

Tall and willowy with chin-length reddish brown hair and chunky glasses, Hale was dressed in loose jeans and a drapey cardigan. Moving comfortably among the sea of kids sitting crisscross-applesauce on the gym floor, she recounted that the first story she ever wrote, in kindergarten, was about a witch who ate babies, noting that its creation coincided with the birth of a new sibling—possibly not a coincidence. The kids giggled with delight—there was something just a little bit naughty about that reference—and supremely relatable.

Thunder Ridge Elementary is part of Utah’s Alpine School District, which made the news last year when parents called for a review of 52 titles and schools removed 22 books from libraries. Hale’s books weren’t on the list, but those with LGBTQ themes were, including Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe and All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson. Most of the propulsion for the purge came from a local conservative group called Utah Parents United, which directed parents to a Facebook group called LaVerna in the Library, a local offshoot of a national network of groups that encourage parents to snap photos of books that they consider unfit for children and send them to local legislators.

On the day that I glanced through the LaVerna page, someone had just shared an article titled “Chelsea Clinton Comes Out in Favor of Porn for School Kids.” A group member commented, “Unsurprising. What was surprising was Shannon Hale & all the Utah authors she got to sign her letter. Which is why I’ll never recommend or read her books again.” The commenter was referring to a petition that Hale had circulated last year, which stated, in part: “We ask our Utah school districts, library boards, state and local governments, and all those in power to reject these divisive, hate-mongering attempts to limit whose stories are worth telling.”

A few days before Hale’s school assembly, I spoke to Trudy Bezant, Thunder Ridge’s school librarian. Bezant said that local elementary schools like hers had been largely unaffected by the book bans, although the previous year, when the district had its wave of bans, a parent had complained about a popular book called Drama by Raina Telgemeier. She did so, she said because it was “along the lines of same-gender attraction.” The parent didn’t end up officially pursuing the complaint, and the book remains in the library. Bezant said she thought the parent might have been concerned because of the book’s graphic novel format, which makes it accessible to younger children who “are coming upon more mature topics,” she said. “For the chapter-book format, they would not most likely be reading it, you know, in first grade.” As for Shannon Hale, she said the school had invited her because of her books’ incredible popularity with students of all ages.

Hale grew up in a large Mormon family in Salt Lake City, where she still lives with her husband and four teenagers. She stopped going to church in 2021. She was crushed that so many Mormons had voted for Donald Trump, but ultimately, it was the church’s “rejection of LGBTQ people, history of racism, and continual subjugation of women” that led her to stop attending.* Though she still sees good in the church and considers herself a Mormon, she didn’t want to raise her children in that environment. Still, there was a genuine sense of loss. “I am Mormon,” she told me over giant plates of mole at the Red Iguana, a Salt Lake City institution that she has been frequenting since she was a teenager. “I was born and raised in it. And generations back—it isn’t like something I can just pluck out of myself. It’s still who I am. But I don’t quite belong there. And I don’t belong anywhere.”

In fact, she always felt different from the others in the tightly knit Mormon neighborhood where she grew up. Even as a young child in the 1980s, she loved reading and writing. But within a religion where girls’ ambitions were restricted to creating a home and having lots of children, she dreamed of being an author. As a teenager, she began to see that being different could not only be okay—it might even be good. Right before she started high school, Salt Lake City rezoned its districts, and Hale ended up at a school across town that was much more socioeconomically and racially diverse than the one she was previously zoned for. “I loved it,” she told me. “I was this white girl in a conservative community, but finding these pockets of space that were very diverse—it opened up my mind to the idea that there’s more than one way to be.”

Around that same time, Hale immersed herself in the world of fantasy books—Lord of the Rings, Narnia, and Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain—and noticed that boys were the protagonists in all her favorites. It wasn’t until later when she had decided to pursue a master’s degree in creative writing at the University of Montana, that she set out to write a fantasy book with a female main character. She had originally envisioned it as a retelling of a Brothers Grimm fairy tale, for adults, but then an agent told her she thought it could fit into a newish genre for teenagers called young adult. “It made sense,” she said. “My internal reader was a combination of when I was 10 to 14, saying [about reading] ‘Oh, this is joy! This is love!’ And it was also me now with my master’s degree and my literary sensibilities.” The book, Goose Girl, was published by Bloomsbury in 2003 and became a critical and commercial success.

Writing for children allowed Hale to channel the kind of joy she had felt as a young reader and over the next few years, her career took off. In 2005, Princess Academy won a Newbery Honor, the highest distinction in children’s literature, with previous winners including E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web and Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby, Age 8. Several more well-received books appeared, including a retelling of the fairy tale Rapunzel called Rapunzel’s Revenge in 2008 and its sequel, Calamity Jack, two years later.

The first Princess in Black book came out in 2014, and sales took off. By this point, Hale was earning enough as a writer that her husband Dean quit the desk job that he never really enjoyed and began to collaborate with her. He also picked up the slack at home—by this point their family was growing—when she was on the road. Hale described Dean as the “ideas guy.” For instance, say she needs a funny name for a restaurant, “he’ll send me an email with 25 suggestions,” she says. “He’s that kind of guy. He’s great that way.”

Her growing fame, however, led to a deeper personal struggle about her identity. When finding out about her religion, people she encountered outside of Utah thought of Donny and Marie Osmond, or Jon Krakauer’s book about fundamentalist Mormons Under the Banner of Heaven. “I don’t want to represent all of it, because it doesn’t represent me,” she told me. “I’m a dissident member of that church, I don’t agree with so much of it. It’s also the loving community that I grew up in, and that my family is from. I have so much love and compassion for them, I’m not going to reject them.”

As we sat and chatted, two moms sharing some Mexican food, at several points, the conversation came back to Shannon’s intense identification with both kids and their parents. She feels for the children who don’t fit in—for queer kids and kids of color and kids struggling with mental health issues—and also for the confused and even frightened parents who may be finding their children unrecognizable. Once, she and two of her daughters appeared at the Utah State Capitol, during an anti-book-banning event where she spoke. As they were leaving, a man shouted at her, “My kids are huge fans of Princess in Black. I am so disappointed in you.” She recalled, “I turned into a therapist! I was like, ‘It’s okay. It’s okay to be disappointed.’ I do feel compassion for him. He is where he is in his life, and he’s doing the best with where he is.”

Then we started talking about children’s books. My two kids are younger than Hale’s, and I confessed that I really hated Captain Underpants, a series by Dav Pilkey that is so scatologically resplendent that I had to ban it before bedtime for my seven-year-old. He was so titillated by all the poop and fart jokes that by the time we finished a chapter, he was practically ricocheting off the bedposts.

“What was it exactly that you dislike about Captain Underpants?” she asked, aside from the bedtime delays of course. I thought for a minute and then answered that I feared that my kid would bring the potty humor to school, and it would reflect poorly on me as a parent. Hale nodded. “This book is subversive to them—they know it’s naughty,” she said. “They know they can’t talk like that in front of their teacher at school. But what a safe way to be naughty.” She gently informed me that there was no possible universe in which my delicate flower was not already making fart jokes with his buddies. With Captain Underpants, she said, Pilkey has “given our voice to the boys who were sent out to sit in the hall, and he said that you still matter. And it’s okay that you find this funny, and you’re still really embraced.” Yeah, she was right. I felt better, actually.

And then I realized: I just had been Shannon Haled.

Back at Thunder Ridge, when the older kids—fourth, fifth, and sixth graders—shuffled in, she asked the boys if they might like to read Princess Academy. “Nooooo!” they groaned in unison. “Many people think boys can’t read a book with ‘princess’ in the title,” said Hale, smiling. “They’re wrong!” Before the boys could protest, she showed pictures of men reading Princess Academy in all kinds of manly settings. “Boys read Princess Academy at the park! They read it with a moustache, with power tools, rock climbing in the Batcave!” The kids cracked up.

She then showed them illustrations from her memoir graphic novel series. A major theme is friendship—the shifting alliances of preteen girls. She described her own school years when a girl in the popular clique was nice to her some days but mean to her the next, seemingly without any reason. On the overhead projector, she showed an illustration that depicted fourth-grade Shannon being tossed on a ship through stormy seas. She asked the kids to raise their hands and tell her how they thought she must have been feeling.

“You’re alone!” called out one kid.

“I’m alone! That’s a great detail. What else?”

“There’s a storm!” shouted another.

“Right, so it feels dangerous,” said Hale. “One more thing I want you to notice is that there are no controls on the boat. There’s no way to steer it. So there’s little Shannon and she has no control. You look at that picture, you get a feeling, and you understand how she’s feeling.”

The thing about culture wars is that there are never any winners. Yet in these highly charged last few years, one group of losers is clear: children. Caught in the middle of raging (and sometimes violent) debates about masks, vaccines, and curriculum, what must they think of the adults who tell them to behave but can’t manage to do the same themselves? The only real constant within this contentious landscape are all the young readers, whose lives literally can be transformed because they read something amazing in a book.

After the assembly, I made my way over to Hale, who was surrounded by a throng of kids and teachers. On the outskirts of the group, I met a ten-year-old girl, one of the only Black kids I saw at Thunder Ridge that day. She was clutching her copy of Best Friends, the second book in Hale’s memoir series, so I asked her what she liked about it. “She explains how she felt when she was a kid in sixth grade,” the girl said, smiling. I asked her if she could relate to the feelings that Hale described. She nodded. “I get shy a lot,” she said softly. “It made me feel at home.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that it was Hale left the church in 2016 because she was crushed that so many Mormons voted for Trump. The sentence has been updated.