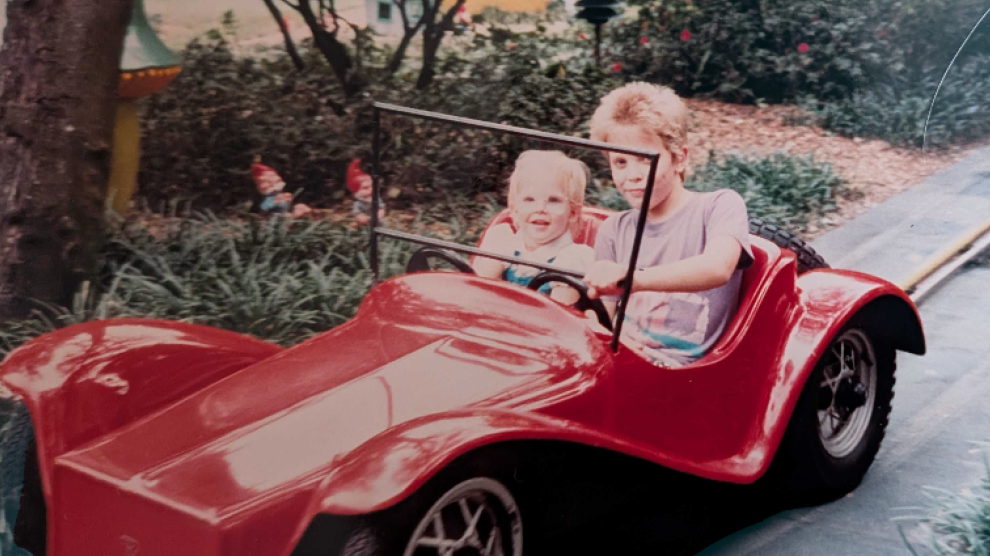

Mother Jones; Photo courtesy of Gabriel Mac

How much would you give up for the chance to tell your story on your own terms? For Gabriel Mac, a trans writer, the lure of writing and publishing free from the confines of “cis publishing” was enough to leave behind thousands of dollars in journalism work, taking him from a six-figure salary to below the poverty line. But the rewards are great: On his new website The Faggot-Witch Whenever, Mac is free to publish at what he calls “the intersection of being gay, being trans, being psychedelic, being an incest survivor, and being fabulous.”

In one of the first entries on his website, titled “Faggot-Witch Forever: A Letter of Resignation to Cis Publishing,” Mac tells us, “it isn’t fun anymore” and questions if it ever was. The “it,” presumably, is a feeling that I, and other marginalized journalists can relate to: trying to make a living and a name for ourselves in a white, cisgender, heteronormative industry. Mac’s writing on his new website is, as usual, incisive, pensive, and funny, as he covers topics like everything he did (or didn’t) do wrong in 2022, sex abuse treatment, and road trips.

Prior to leaving the industry, Mac, who is 42, had a storied career in the mainstream journalism world, including as a human rights reporter at Mother Jones, where he wrote about Haiti’s reconstruction after an earthquake and about working in an Amazon warehouse. After leaving this magazine, he wrote for Rolling Stone, the New York Times, and many others. Working for these outlets, he says, brought him prestige that made it hard to leave the lifestyle behind.

But there were problems. After he transitioned, one publication insisted that he be photographed in his underwear to accompany his story or else they would pull the whole piece. Another refused to publish his account of being sexually assaulted as a child unless he could “prove” it.

For Mac, trying to make it work was quickly becoming not worth it anymore, and no amount of money would make the degradation he was facing as a trans person worth it. Still, it was hard to stop. “I was walking down my street, just going for a walk. And I was like, I could just do one, just one more, just this last [story],” Mac says. “I was just hearing myself in my own brain talking about it. I was like, I sound like an addict…This is not a new or controversial thing to say about survivors of trauma right? You get addicted to the cycle of people harming you—you expect to be harmed, and then you do a thing and you get harmed.”

But finally, he decided to quit. In his “letter of resignation” to mainstream, cisgender journalism, he writes: “As we were negotiating word counts and fees, my therapist asked me how much they’d have to pay to make whatever was going to unfold next worth it. Double? he suggested. They wouldn’t have paid me double. And I had to admit to myself that there wasn’t a number anymore.”

The feeling of wondering if journalism is worth it, despite the benefits, is one that many marginalized journalists have experienced, including myself. Why not take a job in communications or marketing that’s much cushier and pays more? Well, aside from the money Mac was making, he also points out a certain level of clout he gained from being known as a writer: “I can’t think of a single time in the last decade and a half that I answered someone’s What do you do? with the truth that magazines pay me money when it didn’t result in that person being impressed…Now that I read as a man, the response is generally, ‘Wow!’, and I’d be lying if I denied that was what I was going for. I’d entered traditional publishing in my twenties so I could make the connections necessary to publish a book about friends who were refugees, but even an intern’s role garnered me a reverence that was wholly unfamiliar—and for which I was starving.”

I’m familiar with that sensation, too. Especially living in the Bay Area, it’s rare that I don’t get at least a somewhat impressed reaction when asked what I do, be it from the parents of friends to people at dance clubs. And as a queer woman of color, I can’t deny that it’s a good feeling, especially when it comes from authority figures.

A Pew Research survey found that 52 percent of journalists find their news organization does not have enough employee diversity when it comes to race and ethnicity. The work journalists from racial and ethnic minorities do is made even more difficult as they have to cover their own communities: “‘Checking in'” would later become an expected newsroom practice, but at the time, the well-being of my Black colleagues and me seemed like an afterthought. I wasn’t offered time off or even a moment to step away and have a coworker take the reins. Instead, I felt like I needed to desensitize myself to my own oppression,” Nadia Suleman, an editorial producer at Time, told her employer.

The situation is also bleak for trans writers like Mac. In February, 1,200 contributors to the New York Times and more than 34,000 others signed on to a letter regarding the paper’s poor coverage of trans issues: “The Times has in recent years treated gender diversity with an eerily familiar mix of pseudoscience and euphemistic, charged language, while publishing reporting on trans children that omits relevant information about its sources,” the letter said.

Mac faced those same frustrations. “The further I got in my transition, and the further I got in my recovery from child sex abuse, the more I was running into censorship, and accidental, but still very real, harmful interactions with [cisgender] staff,” Mac told me. “They just weren’t as transliterate as they thought they were.”

In an industry that lacks both racial and gender diversity, many of us worry about what the future of journalism will look like. In Mac’s hopeful vision, marginalized journalists will carve their own paths—without having to rely on legacy media to dictate how they tell their stories.