Former CIA Director Richard Helms acted as a personal consultant to Robert Redford for his role in "Three Days of the Condor," which also starred Faye Dunaway.Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

The Central Intelligence Agency has a penchant for producing hagiographic narratives about itself. Its new podcast is no exception.

The Langley Files, which debuted on September 19, bills itself as a show that provides the public with a “unique look behind the curtain,” sharing interviews with CIA officials and other “exciting” guests, educating the world on the agency’s history and mission, and bringing the agency “out from the shadows.” The podcast is hosted by two mononymously named CIA employees, Dee and Walter, with episodes running a brisk 15 to 30 minutes.

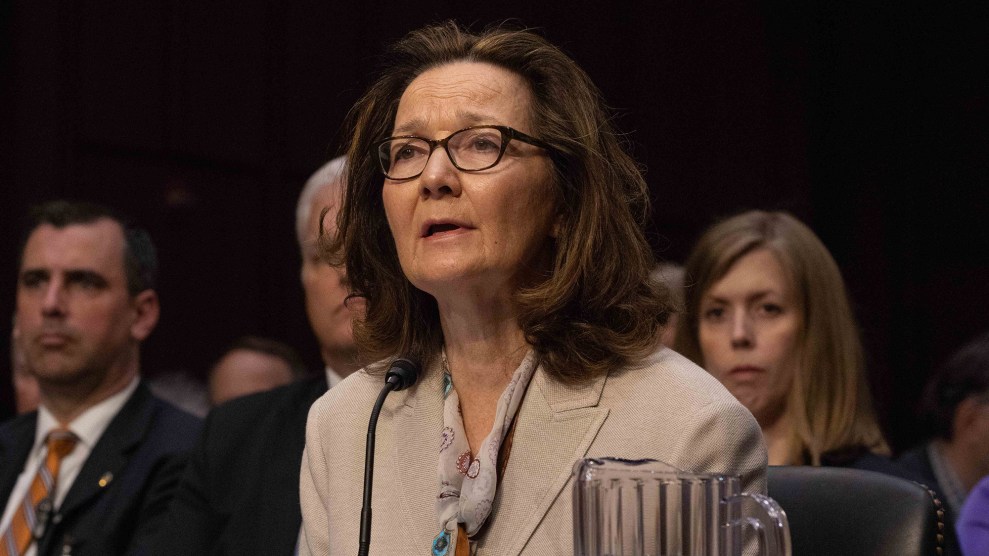

The first episode features an interview with CIA Director Bill Burns, who says, without a hint of irony, that the agency’s first job is not to “bend intelligence to suit political or policy references or agendas,” but rather to courageously tell policymakers what they need to hear. He goes on to list some of the CIA’s recent accomplishments: how it painted a distinct picture of Vladimir Putin’s plans to invade Ukraine months in advance and conducted a “successful” drone strike against al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri with zero civilian casualties—though Burns neglects to mention the long history of civilian deaths from US drone strikes over the past two decades.

Another goal of the podcast, according to Burns, is to counter “misconceptions” about the agency. In real life, Burns says, the CIA is not “a glamorous world of solo operators” like fictional spy legends Jason Bourne or James Bond. Instead, he says, you’re more likely to find people like the super relatable director himself, who claims he doesn’t quite “fit the image.”

“I’m most comfortable driving our 2013 Subaru Outback at posted speed limits. The height of technological daring is when I can finally get the Roku to work at home,” says Burns, in a transparent attempt to assure listeners that the head of the agency accused of multiple war crimes is, in fact, just like them.

When the podcast debuted a couple weeks ago, media outlets such as NPR claimed it was “extremely rare” for the CIA to seek public attention like this. But historian David S. McCarthy, a professor at Richard Bland College of William & Mary, says that’s not necessarily true. “The podcast is definitely classic CIA public relations,” says McCarthy, pointing to a long line of attempts by the agency to rehabilitate its murky history through tried-and-true PR tactics.

When it was founded in the early years of the Cold War, the agency was relatively unconcerned with public relations; few people even knew it existed, and fewer people knew the extent of its operations. But by the 1950s, the CIA had reached the height of its influence and power, which brought with it public scrutiny.

As historian Christopher Moran writes, as early as the 1950s, Mary Bancroft, a celebrated intelligence analyst for the Office of Strategic Services, wanted to create an educational television series on the evolution of US intelligence from the American Revolution to the present. She admired how the FBI marketed and publicized itself, and how television documentaries produced by the Air Force helped “create in the public mind an impression of its usefulness.” For the CIA, she imagined a television series with a narrator “in whose mouth can be put whatever ideas the service…wishes to get across.” One form of PR was its funding of the animated classic 1954 anti-communist propaganda film Animal Farm, for which the agency paid the American film producer Louis de Rochemont approximately $500,000—or about $5.5 million today.

In the ensuing decades, the agency’s mystique began falling apart as investigative journalists, congressional committees, and tell-all exposés by retired agents constructed a grim history of the CIA’s transgressions. To name just a few well-known examples, there was the overthrow of Iran’s Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, which sowed the seeds for the Islamic Revolution of 1978–79; the CIA’s failed attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro at the Bay of Pigs in 1961; its much-derided 1968 Phoenix Program, which pushed to capture, torture, and assassinate Vietnamese communists; and its support of the military junta in Chile in 1973—all of which contributed to the erosion of public confidence in the agency. That’s when the CIA’s PR efforts went into overdrive.

According to McCarthy, the agency established a modern PR office in the aftermath of “the Year of Intelligence,” a period between 1975 and 1976 when key intelligence agencies were being investigated for their abuses and wrongdoings. The investigation of the CIA included shocking revelations of illegal human experimentation under Operation MKULTRA, as well as the agency’s surveillance and wiretapping of American journalists and newsrooms, and its attempt to poison Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba.

David Atlee Phillips, a self-proclaimed “propagandist” for the CIA, was the face of many PR efforts in the 1970s, writing books and speaking at universities in an effort to counter the more negative, tell-all memoirs being published. These PR initiatives allowed the agency to try to craft an image of openness and transparency—just as it attempts to do in its new podcast.

“It’s always good to demystify this agency, given that there are still different public perceptions of this place that are shaped by films, books, and a ton of preconceived notions of what a ‘spy’ does,” says Bonnie, an analyst and public affairs officer at the CIA, in episode two of The Langley Files. But what Bonnie fails to mention is that the agency has been working directly with Hollywood since its founding in order to shape that very image through film and television. In the 1990s, the agency launched an official entertainment liaison office to help assert its usefulness in a post-Cold War world and soften PR disasters. The CIA’s involvement can be seen in movies and shows like the film Zero Dark Thirty (whose filmmakers had unprecedented access to the agency’s files related to the killing of Osama bin Laden); the TV show The Americans (one of its creators, Joe Weisberg, is a former CIA agent, and the show’s scripts were subject to approval by the agency, lest Weisberg divulge still-classified information), and Homeland (which was a favorite at Langley).

It’s unclear why exactly the agency has decided that now is the time to move beyond film and TV and get into podcasting, though it could be a sign it’s looking to pique the interest of the next generation of recruits as it faces increased competition from companies like Amazon for talent. (One 30-year veteran of the agency, Kathleen, alludes to this possibility in the second episode of The Langley Files: “In order to attract and retain the workforce we need, to protect our nation, to stay one step ahead of our adversaries, we need to share a bit of what we do here,” she says, when asked why the public should be interested in the show.)

But whatever the reason for the CIA’s renewed PR push, it’s nothing new. The agency has more than 50 years of reliable PR strategies to choose from as it tries to polish its veneer of credibility as a trustworthy institution.