The consequences of accidents and intentional violence often look the same. Here, a cyclist honors those who died in the October 31, 2017, vehicular terror attack on Manhattan's West Side bike path.Andres Kudacki/AP

Last year, while cycling in Denver, I maneuvered over what I thought was part of the road, hit a curb, and fell. I wasn’t going very fast, but the right side of my body still smashed into the concrete. As I got up, a woman who lived nearby came over. She told me that she saw people trip over that curb all the time.

So, was that an “accident”—or the predictable outcome of a design flaw? Think about the last time you got hurt by accident. How could that have been prevented, and what will you do to ensure that other people won’t experience the same?

Those are the sorts of questions that Jessie Singer dares readers to ask in her 2022 book, There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster—Who Profits and Who Pays the Price. Drawing from history, interviews, and personal experience—her best friend died when a drunk driver struck him on his bike—Singer examines the conditions that lead to “accidents,” from nuclear meltdowns to drug overdoses to slip-and-fall injuries.

I caught up with Singer to discuss this little word that, in her view, stands in the way of structural changes that can make our lives safer. We talked a lot about cars.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What is an accident?

Traditionally, the dictionary has two definitions. One is that an accident is a random event, and the other is that an accident is a harmful event. At once we’re saying: An accident is unpredictable but with a predictable outcome.

But researchers have found that when we hear the word “accident,” we actually think “unintentional,” which is neither of its definitions. In a practical sense, when we talk about the more than 200,000 people that are killed, quote unquote, “by accident” every year, we’re talking about unintentional injury, which includes everything from fires to traffic crashes to poisonings to drug overdoses to drownings.

When you say “there are no accidents,” what do you mean?

I mean not only that the word “accident” is a trick—a game that we’re playing to avoid looking at and examining a preventable problem—but that nothing we’re talking about here is random or unpredictable or unpreventable.

If accidents were random, then injury-related death would fall randomly across the country. It does not. Black people die in fires at twice the rate of white people. Indigenous people are struck by cars at twice the rate of white people. People in West Virginia die by accident at twice the rate of people in Virginia. Policy decisions, unregulated corporate power, and the differential distribution of resources lead to risk unequally distributed across the US. These are not accidents. These are predictable, preventable events—the results of how we allocate safety across the country.

I was struck by the example of the study that showed that drivers are less likely to yield to Black pedestrians.

We often think of accidents as a matter of personal responsibility, but really what we’re talking about here is a matter of risk exposure. A Black man trying to cross the street might be exposed to more risk because they are Black and, because the majority of drivers are racist, they’re less likely to yield. But they also might be exposed to more risk layers that stack up beyond that, like the fact that we spend less money to make roads safe in Black communities. Each factor is a risk exposure, and the fact that some people are exposed to more risks adds up to these unequal rates of injury-related death.

I like how you extend a bit of grace to people who use the word “accident” in certain scenarios. You wrote in the section on stigma that “when a powerless person says ‘it was an accident’…it can mean that an overdose was unintentional, or that any consequence was regrettable…And if ‘accident’ can offer that person some kindness and absolution, that is a story I want us all to hear.”

I don’t think it’s my place to say who should or shouldn’t say the word “accident.” I came to this book having helped a group of predominantly mothers who’ve lost children in traffic crashes start a campaign against reporters and police using the word “accident” to describe traffic crashes. But when I sat down to write an entire book about this word, I realized that the answer for me, personally, wasn’t word policing. It’s getting people to ask these critical questions, so that when they hear the word “accident,” instead of saying, “Don’t say that,” they say, “Was it really an accident? How could it have been prevented? What can we do next time?”

Do you think that there’s a tension in the safe streets movement between a desire to punish people who drive recklessly and a criticism of the carceral state and the way that policing is often racist and discriminatory?

I think that the way that people who ride bikes and walk feel threatened by drivers and take that on as an interpersonal fight has led to an over-reliance on punitive solutions, on policing as an answer. Policing is totally ineffective at solving any problem of accidental deaths, traffic safety included.

The urge to punish is reasonable and understandable—it makes people feel better—but it’s not going to solve the problem. William Haddon, the first administrator of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, said, “We’ve all been miseducated that the way to solve this problem is to have more squads of police chasing Americans so that they wouldn’t drive 120 miles an hour, rather than arranging cars so they can’t go that fast.”

It’s the difference between a punishment and a solution. Imagine a city where every time a person was killed in traffic, instead of us calling the cops, we called the designer of that road, and we said to the Department of Transportation, “How did you design this road where this was allowed to happen? How are you gonna fix it?” This is not a matter of personal responsibility, but the design of the system that we’re providing for people.

I read this book in the weeks after the Uvalde elementary school shooting, and I kept thinking about the many factors that allowed for such a terrible outcome, from the ease with which the shooter purchased a gun to the insufficient police response. What does a tragedy like that have in common with an accident?

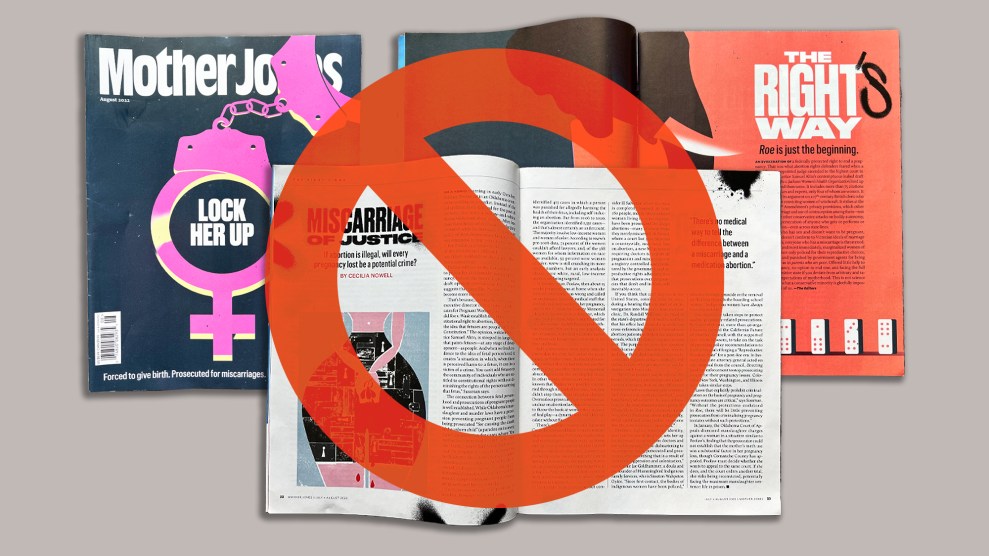

Accidents and violence are not so different if we look at them not as punishable acts made by bad people, but as preventable harms. Through this lens, we can actually fix both problems at the same source. The solution to the mass shooting is also the solution to the accidental shooting. The solution to the traffic crash is also the solution to the vehicular terrorist attack.

My best friend Eric was killed in 2006. He was a 22-year-old New York City high school math teacher, riding his bike on a separated biking and walking path that runs along the west side of Manhattan. He was killed by a driver who mistakenly turned and entered this biking and walking path. That driver was drunk and speeding. He went to prison.

Eleven years later, a different man rented a truck and followed the same route, except this person intentionally turned on to the path. They killed eight people and injured 11 in an act of vehicular terrorism.

Others had been killed on this same path. But every time, before the terrorist attack, the story that was told was “it was an accident,” and the dangerous conditions remained.

After the vehicular terror attack, the city and state blocked every possible entrance to this biking and walking path with steel bollards and cement barricades. They made it impossible for both the accident and the violence to occur.

The point of the accident narrative is to maintain and defend the system as it is, to define the incidents as an aberration, not a predictable result. If we decide that a house fire is an accident, it means the building is fine, the regulations are fine, the laws are fine, and the problem is irresponsible people who let a fire start. If you know that Black people are killed in house fires at twice the rate of white people, and you see those fires as accidental, you’ll also see Black people as fire starters, as irresponsible people. The accident narrative becomes a justification for racism and social inequality.

Only after someone intentionally drove onto the bike path did officials take steps to prevent similar events from happening in the future.

Seth Wenig/AP

What can people do on an individual level to prevent so-called accidents?

Even in your own community, there’s a million ways to prevent so-called accidental death.

If you advocate for traffic calming and public transit expansion, you will reduce accidental death because people on the bus are far less likely to be killed or to kill in a traffic crash. If you fight for safe injection sites and the free distribution of naloxone, you will reduce the likelihood of an accidental overdose. Fighting for ADA accessibility measures, like ramps and grab bars in your home and workplace, reduces the likelihood that anyone will die or suffer an accidental fall, which is the third largest cause of accidental deaths in the US.

Those things don’t prevent mistakes, they just prevent harm of our mistakes. To err is human. Mistakes are inevitable, but our failure to protect people is not.